In 1930s St Louis, Missouri, housing laws ensured black people and white people lived in separate neighborhoods. Racial inequality was rife and the city as a whole, like the rest of the US, was suffering the effects of the Great Depression. The Wingfield family are no different – living in a tenement apartment, Amanda and her grown children, Tom and Laura, struggle to make ends meet. Stress, worry, and resentment drive wedges between them creating a tension stoked by Tennessee William’s exquisite language. In this production directed by Femi Elufowoju Jr, the Wingfields are black, so their dreams and aspirations are all the more devastatingly unreachable when contextualized by the segregation of the day.

There are moments and individual lines that particularly resonate with the Wingfields as a black family rather than a white one, particularly during scenes anticipating the visit from one of Tom’s (white) colleagues, who Amanda hopes will rescue her daughter from poverty, and his visit. His arrival leads to him exoticizing her as ‘different’, and when Amanda and Laura’s expectations are smashed, the two are left in tears by a white man. More broadly, this family is not just victims of capitalism, but of racism as well – no matter how much ambition they have, they cannot be treated as equal to white people.

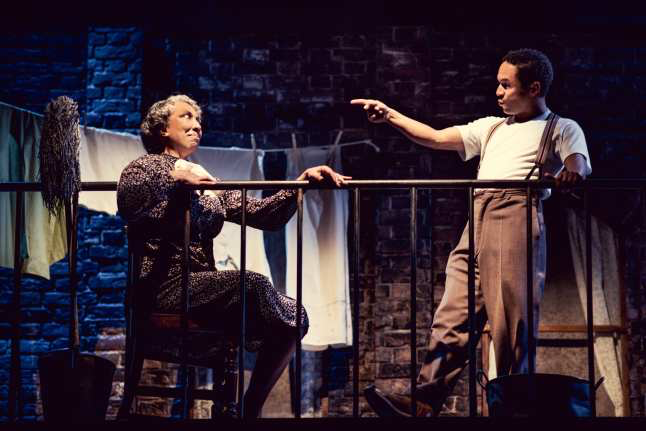

Amanda Wingfield lives in the glory days of her youth in the Mississippi Delta, where gentleman callers, debutante balls and wealth were plentiful – her descriptions stand in stark contrast to the worn furnishings and bare brick wall of Rebecca Brower’s set. After the Civil War ended there were soon many black farmers in the region, but the state’s racist laws caused many to eventually lose their land and money – this history makes her current urban poverty all the more profound, as her disenfranchisement is likely down to more than her long-absent husband. Played by Lesley Ewen, she is a grand dame rendered both fabulous and ridiculous as she regales her children with the same old memories, and peacocks around their home in front of a visitor. Her ability to be simultaneously charming and pathetic evokes sympathy, wonder, and pity.

Michael Abubakar is a splendid Tom. The tortured artist is a furious bird much too big for his cage and with ambition as vast as the skies, but he is also charming and vulnerable. The dual care and frustration that he carries for his family are undoubtedly relatable, and any creative – bar the most wildly wealthy and successful – will feel his pain of responsibility for the rent and bills.

As brash as Abubakar is as Tom, Naima Swaleh as Laura is delicate. She is also bird-like, but rather than an eagle, she is a hummingbird. She slowly flits around their confined flat, freezing or darting off the moment anxiety hits. In combination with the rest of her family, she is perhaps the most confined – but by her own mind more so than the circumstances around her. Her performance provides excellent balance to the others.

Though more plays by black writers are sorely needed on British stages, this revival of an American classic is given new, unfamiliar, and achingly resonant life with its kitchen-sink drama set in the home of a black family. Today’s racism and economic precarity are also recognizable and serve as a warning to save ourselves before it is too late.

This article was originally published in The Play’s The Thing on May 30, 2019, and has been republished with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Laura Kressly.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.