Seeing a play you much admired five years ago for a third time isn’t always sensible. Will it be as good as you remember it? I saw Jauría, Jordi Casanovas’ verbatim play based on the case of la manada twice in 2019 and found myself writing about its impact across different fora. Based on the rape trial that galvanised women across Spain to take to the streets in protest at the country’s antiquated rape laws, the production played to full houses, touring extensively across Spain and beyond with an accompanying education programme. The case of la manada shocked the nation with an impact that is still felt in 2024. Five men from Seville, part of a group naming themselves la manada (the wolfpack), raped an eighteen-year-old student from Madrid on 7 July 2016 while visiting Pamplona for the San Fermín celebrations. They filmed the assault on their mobile phone, WhatsApped friends about the act and abandoned the woman in the hallway of a building after stealing her mobile phone. It became a reference point in modern Spanish history, kickstarting the #MeToo movement in Spain and leading to a change in the country’s rape laws as well as prominent discussions about the misogyny underpinning Spain’s judicial structures and wider society: one of the gang was a member of Spain’s rural police, the Civil Guard, another a soldier in the army. Sexism was exposed as an ugly part of Spanish life.

I am watching the play again in April 2024 in a very different context. Teatro Kamikaze departed the Pavón theatre, their Madrid home, in July 2021. Covid-19 has come and left an indelible mark on the performing arts scene. There are new global conflicts and the sense of a world that feels more febrile and brittle than in 2019. Miguel del Arco’s restaging comes eight months after the President of the Spanish Football Federation aggressively and non-consensually kissed the footballer Jenni Hermoso as the World Cup Winning Football Team were receiving their medals on 20 August 2023. The act unleashed another wave of mass protests in Spain, exposing the sexism that problematically passes for “normal” in too much of Spanish culture, and drawing condemnations from politicians — one Minister commenting that she hoped the situation would be met with appropriate and decisive action rather than the judicial leniency meted out to la manada.

Miguel del Arco’s restaging of Jauría is not a completely new production but to see it as a revival would also be an error. For del Arco effectively presents a dialogue with his earlier staging, but one that functions on its own terms: a reflection on what the play means and why, I would argue, it still matters five years on. The script, by Jordi Casanovas, is carved from the trial transcripts. The cast is completely different and, in the case of la manada, the actors bear an uncanny physical resemblance to the characters they are playing. The stocky cockiness of José Ángel Prenda, the gang’s leader, known as El Prenda, is present in Artur Busquets’ adept characterisation; the distinctive moustache and tall lean demeanour of soldier Alfonso Jesús Cabezuelo is captured by David Menéndez. Carlos Cuevas delivers the complacency of Antonio Manuel Guerrero. While images of the woman never circulated, Ángela Cervantes presents a slightly older and physically more robust Her or Ella — as she is referred to in the play — than María Hervás’ frail figure; the woman is never named in the play, respecting the trial’s insistence on anonymity.

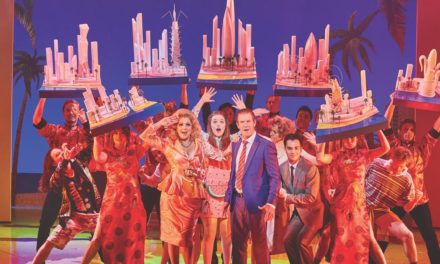

Her surrounded by the predatory wolfpack: Photo: David Ruano, courtesy of Teatro Kamikaze

Alessio Meloni’s set boasts the same tiled alcove and sense of claustrophobia of the design he provided for the 2019 staging; high walls and a barred window stage right highlight the sense of containment. Six chairs are harnessed to create the different environments — bar, streets, courtroom. José Novoa’s costume design — different to that provided by Meloni for the 2019 staging — opts for the red, white and black t-shirts and red neckties with San Fermín logos which la manada could be seen wearing in photographs of the group partying in Pamplona. The attire captures the sense of a bacchanalian space where anything goes. Casanovas’ Her also sports the distinctive red necktie of the San Fermín celebrations. The men’s attire is swapped for polo shirts for the trial, Her simply places a grey jacket over her white t-shirt. The male actors place the robes of the judiciary over their shirts as they move from la manada to take on the roles of the judge and la manada’s defence lawyers. Costume changes are brisk and functional.

The actors playing “la manada” double as the defendants’ lawyers. Photo: David Ruano, courtesy of Teatro Kamikaze

There is a lithe theatrical energy to del Arco’s production. The director deploys flamenco to situate the gang as Andalusian with their moves evoking the goading of the bull. The men move like a pack, they complete each other’s sentences, they cover each other’s backs. This is not to say that the gang are not individualised. Ángel Boza (Quim Ávila), the newest member of the group is often positioned on the margins, never in the centre unlike Busquets loud, overbearing El Prenda. Boza wears his necktie as an armband, differentiating him from the rest of the gang. Cabezuelo (David Menéndez) sports a headband, the soldier misconceiving himself as a warrior — the hachimaki headband a symbol of determination and effort in Japan. Guerrero (Carlos Cuevas), bounces around the stage, believing his role as a Civil Guard makes him untouchable. Francesc Cuéllar’s Jesús Escudero is keen to be part of it all, his head stretching out ensure he is not left out of any of the action.

La manada creating the percussive rhythm of the bar as Her recounts what happened that night. Photo: David Ruano, courtesy of Teatro Kamikaze

The friends party as one, creating the sound of the pulsating pop music in the bar in which they meet Her with chairs helping with the percussive rhythm. The rape is realised in the alcove and staged symbolically — the woman’s body engulfed to the point where she simply disappears into a mass of male bodies. The men’s bodies engulf her; their hands tugging her face from side to side as if she were a rag doll, a torch (its beam like that of a mobile phone) handled by one of the men provides a darting light source that accentuates the sense of panic and chaos. The torch goes off when Her states: “quería que acabara/I wanted it to be over”.

Post rape, Her is jittery and weepy; she positions herself on the opposite side of the stage from the men and faces away from them. La manada convert themselves into the judiciary, donning the formal robes of the legal profession. Busquets sets aside the role of the group leader El Prenda to take on the role of the Presiding Judge in the alcove while the other four members become the lawyers for the defendants. They surround her like predatory crows, again using their chairs as props. They are crisper in their moves than the sprawling manada, more tightly choreographed as they sit together as one. They bounce their legs, like a nervous tick, almost like a growing irritation with the woman’s defiance. As the trial progresses, they move closer in; their moves echoing (but never replicating) those of la manada. The questions get more rapid and frenzied, they move closer in, until she screams out and they back away.

With the interrogation of the woman complete, the actors remove their robes and Ángela Casanovas reappears as the Prosecutor questioning the members of la manada. The men are now dressed in polo shirts and formal trousers and their responses make clear that they do not conceive of what they did as problematic or criminal: whether it is filming a sexual act without consent and then showing it to others; or asking how she is; or grabbing her head to perform oral sex. Cabezuela’s comment that “Yo creo que fui de los primeros y yo recuerdo que me fui porque al mantener relaciones sexuales seis personas en un habitáculo tan pequeño olía un poco mal./I think I was one of the first and I remember I left because, after six people had had sexual relations in such a confined space, it smelt a bit bad” produced a gasp from members of the audience — one of a number of instances where the comments of the defendants produced audible gulps of incredulity from spectators. Casanovas’ Prosecutor walks around the members of the gang as they sit in a row, seemingly trapped on five chairs, each increasingly uncomfortable at being questioned about what they regard as ‘normal’ behaviour.

The sound of the crowds outside the courtroom chant support for Her. An offstage recorded voice narrates the different decisions taken by the courts: a nine-year sentence for sexual abuse (because of the alleged lack of violence and intimidation) rather than the more serious sexual assault (rape) from the initial judgement at the Provincial Court of Navarre in April 2018; the sentence confirmed following the appeal at Navarre’s High Court of Justice eight months later; and then a fifteen-year sentence for rape in the Supreme Court’s verdict on 21 June 2019. The offstage voice was that of Israel Elejalde (anthropologist Arturo in Almodóvar’s 2021 feature Parallel Mothers) in the 2019 staging; in 2024, it is assistant director Carla Tovias who takes this pre-recorded role. The authoritative voice, delivering the “facts” of the case is now that of a woman. While this key information is narrated, the male actors put on the robes as they deliberate the decisions of the different judges who handed out the sentences. But at the staging’s end, it is not the judiciary who are placed centre stage but Her. The actors read out the WhatsApp chat from the front of the stage but when the horrific boasts of group rape are over, they go to the back of the stage and it is Her whose testimony is prioritised. She stands alone, speaking of her whole life ahead of her. She faces forward, they do not.

The standing ovation at the 6 April performance speaks to the impact of the piece. “I listened to a feature about it on the radio and I had to see it” one member of the audience mentioned while leaving the theatre. Del Arco’s production balances the verbatim testimony with a theatricalised register and impeccable performances where the thematics of misogyny resonate across both the action of la manada and their lawyers. The patterns are reinforced to ensure that no part of the system is left off the hook. Jauria encourages reflection and discussion to ensure the case of la manada and its legacy remains very firmly in the public gaze.

Jauría opened at the Teatre Sagarra, Santa Coloma de Gramenet on 9 February 2024, it is currently touring until 8 June 2024 with a run at the Teatre Romea Barcelona from 4 April to 5 May.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Maria Delgado.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.