Dedicated to the 35th anniversary of the musical Miss Saigon, an exclusive interview with the composer Claude-Michel Schönberg.

This year the West End production of the musical Miss Saigon celebrates its 35th anniversary, music by Claude-Michel Schönberg, lyrics by Alain Boublil, book by Alain Boublil and Claude-Michel Schönberg. Three years later the show premiered on Broadway. Both the British and American production runs were successful and rather long: for almost ten years the musical was performed on the stages of the two most important capitals of musical theatre in the world, on both sides of the ocean. The composer and author of the book, Claude-Michel Schönberg – the creator of one of the longest-running musicals on Broadway – Les Miserables, explains the reason for Miss Saigon’s success thus: “First of all, it’s due to the subject – it’s a wonderful subject. Everybody understands the sacrifice of a mother for her child – it’s the basic instinct in our guts. And at the same time, it’s the kind of story that’s happening every day all over the world.”

As we know, any musical consists of two very important components: the story (the book) and the music. In the case of Miss Saigon, the main storyline is based on the libretto of a famous opera by Giacomo Puccini Madama Butterfly, which is a rare occasion in the world of musical theatre. The only ones that come to mind are the musical Aida, with music by Elton John and lyrics by Tim Rice, based on the opera by Guiseppe Verdi of the same name, and Jonathan Larson’s rock opera Rent, partially based on the libretto of the opera La Bohème by Puccini. Taking into account modern realia the story of Madame Butterfly – Cio-Cio-San – was slightly changed in the musical. Not only was the suicide method changed from hara-kiri of a Japanese Geisha to a self-inflicted gunshot by a girl from a Vietnamese bar (Kim) in the musical. Cio-Cio-San didn’t even think of parting with her son, it was the boy’s American father who insisted on taking the child to America for the sake of his future. The dream of a “brighter future” seems convincing enough, but the separation from her son turns Cio-Cio-San’s life meaningless. And she is preparing her wakizashi – a Japanese short sword, “choosing to die with honor rather than live in shame.”

In the musical Kim is driven by desire to send the boy away so that he could live with his American father for the sake of a full and prosperous life. On her track to achieve this goal, Kim fatally wounds herself, to force the child’s father (Chris) to take the boy, despite the categorical refusal from Chris’s American wife – she didn’t want the responsibility of “raising someone else’s child.” So, there we have it, if Cio-Cio-San commits suicide because she cannot live without her son, Kim sacrifices her life to make her son “an American.” Not only the motivation of the leading character was changed. The attitude of the American wives towards Bui-Doi (Bui-Doi – means children conceived during the War, Amerasian children left behind after the Vietnam War) – “the children of war…” In the opera the actions of the American marine sergeant, who deliberately deceived the fifteen-year-old “native,” lead to repentance, regret, and sincere desire to “fix” the situation: Chris and his American wife want to take the boy with them to the U.S. and are willing to take care of him and raise him as their own. In the musical, Chris had to leave Saigon urgently due to the approach of the attacking forces of the Vietcongs, and during the following years, he lived with a belief that Kim died. Chris’s friend – John, works in an Operation Baby Lift organization whose mission is to reconnect Bui-Doi with their American fathers. He is the one to tell Chris about Kim still being alive and about their son. He shares that they are languishing in Thailand. They fly to Bangkok with Ellen, Chris’s American wife, and reunite with Kim. That is where the tragic gunshot takes place. Kim’s last words repeat back Chris’s promise, given to her on their wedding night: “How in one night have we come so far?” Whether the creators of the musical did it internationally or not, the finale of the story became more dramatic and… pragmatic.

The opera Madama Butterfly, written by Puccini and based on the story of the same name by John Luther Long (1898) as well as the autobiographical novel that the story was based on – written by a French author Pierre Loti Madame Chrysantheme (1888) describe the events during the times of the “civilizing mission” of France, in such countries as Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos. At the time only Thailand was able to avoid the French protectorate. It was also the times of the “advanced” West and the “secluded” East, which manifested itself vividly during the first meeting between the Americans and the Japanese. The American worship squadron arrived in Japan to establish diplomatic and trade relations in the middle of the 19th century. However not every time a mutually beneficial collaboration could be established without the gun’s use… That is the time that we travel to in Puccini’s opera.

When the American forces were leaving Vietnam after the Indo-China war (1955-1975), the issue of “the children of the war” was sharp and quick to arise.

In the mid-80-s a photograph of a young Vietnamese woman holding a crying little girl, giving her child to an American soldier so that she could leave for the U.S. and be with her father, drew attention of Claude-Michel Schönberg and evoked strong feelings, reminding Claude-Michel of the story of Madame Butterfly: “I saw a picture of a young Vietnamese girl leaving her mother behind at the airport and I thought that for the mother who has been searching for her ex-boyfriend, it was a huge sacrifice – she knew that if she found the guy it would be the last day for her with her daughter. This picture was a huge shock to me as a father. I could imagine my son leaving me forever back when he was a child. Or I would think of my mother – This could be the last time that I see her. It was a horrendous notion. I’ve been obsessed with that idea of Miss Saigon for a while, and I told Alain Boublil we should set the show up at the end of the Vietnam War. And turn it into a story of а young American soldier and a beautiful Vietnamese girl. And we immediately set off to work.”

And that is how the idea for the book of Miss Saigon the musical was born. We asked the composer and author of the book of the musical Miss Saigon why he chose to use the libretto of the opera by Puccini Madame Butterfly as the basis for his musical.

Claude-Michel Schönberg, Photo from Mr Schönberg’s personal archive

Claude-Michel Schönberg: Miss Saigon is based on a French novel by Pierre Loti Madame Chrysantheme. The writer had an experience in Japan where he temporarily married a Japanese girl. In the middle of the 19th century, they didn’t care about marrying somebody and then leaving them to go back to their country. So, he told this story in his novel. David Belasco used the novel as the basis for his play. And when Puccini came to London, he saw the play once and thought that it was a great subject for an opera. So, he wrote his opera Madame Butterfly. At the same time, he wanted to write Les Miserables. But his lyricist thought it was much too complicated. So, Puccini wrote Madame Butterflyinstead. I am grateful to Puccini for having written Madame Butterfly and for giving up on the idea of writing Les Miserables. Puccini’s work is a direct inspiration for me – Madame Butterfly transforming into Miss Saigon.

Lisa Monde: In other words, nothing has changed since the turn of the century, when Puccini’s opera premiered: no matter who and why came to the foreign country with its culture, traditions, and beliefs – people still fall in love, children get born, there is an issue of mixed marriages and the tragedy of “the children of war” is still relevant today?

C-MS: It is eternal.

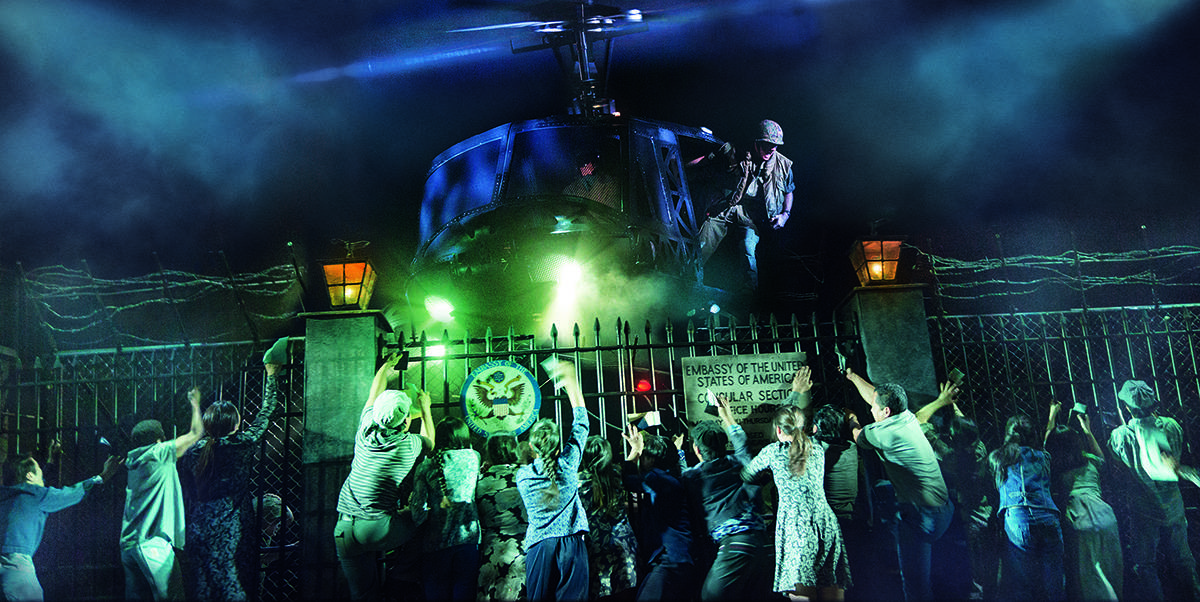

LM: I believe that many people who saw the musical Miss Saigon experienced the feeling of Déjà vu when they saw the pictures representing life after the 20-year-long military operation of the US in Afghanistan, that has spread all around the world. The urgent withdrawal of troops from the Western alliance was completed in August 2021, forty-six years after the end of the US-Vietnam war. The scene in the second act, where the “last” helicopter appears, the last chance of escape from the country – felt identical, was it done on purpose?

C-MS: I remember watching the pictures from Afghanistan with the people running after the plane that was about to take off… When I saw those pictures, I called Cameron [Cameron Mackintosh, producer of Miss Saigon] and told him: “We are going to change ten words in the show, and we can call it Miss Kabul …” And it was 40 years after. So, we have learned nothing of nothing of nothing.

LM: Miss Saigon is very atmospheric; the oriental sounds of instruments make it special but it’s also the music that you wrote inspired by the oriental music. You can hear it in the melodies.

C-MS: Yes. There are a lot of Asian cords. But when Puccini wrote Madame Butterfly, he was living in Viareggio, and he went to Firenze to meet the wife of the Japanese council. She has been singing him traditional Japanese songs, so the very ending of Butterfly – that’s the Japanese traditional music. Puccini was always searching for new things and new inspiration. When Puccini was writing Turandot, he received an invitation from Arnold Schönberg, my relative. Arnold Schönberg for the first time had a concert in Milan. And he invited Puccini to come to the concert. Puccini had a score of what he was going to listen to in the car with him on his way to Milan, he was studying the score. Puccini went to the concert, and he was the only one not to “boo” in the audience. When he went home, he told his wife that he had heard something beyond his comprehension – “that’s the future and I will never be able to achieve it.” He was very conscious of his own abilities and what was needed for the music in the future.

LM: It’s so interesting that your connection with Puccini goes generations back! How do you feel about the fact that here in the US the musical not only has an army of fans but also quite a few ideological opponents?

C-MS: For the moment, it is hard for us to have a show of Miss Saigon in America. Things have changed. We had an issue with the MeToo movement and the woke community about the wrong image of an Asian woman – as if we present them all as prostitutes. There is even a theatre play called Fuck M…S… But strangely enough, it’s not happening in Japan or Austria and even Australia, where last year we had a wonderful production of Miss Saigon.

LM: Did you make any adjustments to the music for the foreign-translated productions?

C-MS: Of course not. If the producers want to do the show, they work with what I wrote. I am very paranoid about that. I did everything in a way that I did for a very good reason! But I am always excited to help them through the new vision of the show. Our show is telling a precise story and if they don’t explain the story through their direction we have to say – no. I just always want to make sure the show is on a proper level, and there are a lot of people who don’t understand the concept of acting through song… Also, many things depend on the director. But not every director knows how to direct someone who is singing and not acting per say. I am always ready to help whoever is working on the production, even some teams that are rehearsing the show in a very remote city.

LM: Can you name some recent productions, that were the most successful in your opinion?

“Miss Saigon”, the Crucible Theatre, Sheffield – (L) Christian Maynard as Chris, (R) Jessica Lee as Kim and Company/ Photo credit by Johan Persson

C-MS: Last year we had a production in Sheffield at the theatre called The Crucible – it is a very prestigious theatre. All their productions end up in London – the quality of their work is fantastic. There were two guys who wanted to do Miss Saigon. They were not concerned about the racial issue; they ran the show for two months and it was one of the most successful productions. Many people from London came to see it. The production was totally contemporary; there was almost no set, there was only a golden wall, and everything was done with the help of the light and choreography. It allowed the audience to create everything through their own imagination.

LM: Was this a new, reimagined interpretation of the musical?

C-MS: So, in the production of Miss Saigon in Sheffield –they changed something and were not aware of it. The Engineer was played by a woman – Joanna Ampil- because in Southeast Asia and Japan, you have what they call mama-san– that is a woman who runs a brothel, a restaurant – everything. And Joanna did it beautifully – she is a very strong woman. From this point of view, all women, including Kim – are very strong women. They are not victims of the situation. They are not doing prostitution because there is a pimp that is abusing them, they are doing it because they need to survive and that is what they need to do, to feed their families, and earn money. And even in the first song The Movie in My Mind, there’s an explanation of why they’re doing this and that there is no other way for them because they need to feed their families. They are good girls.

“Miss Saigon”, the Crucible Theatre, Sheffield – Joanna Ampil as The Engineer/ Photo credit by Johan Persson

LM: That is very important – a positive and respectful attitude toward the barmaids who are forced to do what they do to make a living. The spectators in South-East Asia always pay attention to that.

C-MS: Once I had dinner with an important American movie director – he wanted to make a movie out of Miss Saigon, he said: “But at the end, this girl Kim – she’s a prostitute.” And after I heard that, I told him: “You’re not going to make that movie.” Because it meant that he didn’t understand the characters at all. I advised him to go to Bangkok or the Philippines, do some research first, and then when he came back, we’d talk about it again.

LM: Do you usually participate in the casting for your shows? Do you have a say when it comes to people who are playing the main roles?

C-MS: I’m very paranoid. We [with Alain Bоublil] are involved in the casting process; it is stated in our contract. There is a brand-new production of Les Mis in French in Paris, I keep traveling to Paris and attending the auditions. There are plenty of singers, but they are too classical, they do not understand how to act through singing. We keep things under control as much as possible, I don’t attend this part of the process, for example, in Oslo, but we have a great team of directors. We are all passionate about the shows, we love what we do, and we always want to protect our creation.

LM: Do you have a favorite performer of the part of Kim in Miss Saigon, from all the different productions that the show had?

C-MS: There is a video on YouTube of me meeting Lea Salonga for the first time, I met her in the Philippines. She was sixteen at the time. And she was so talented. We have been searching all around the world for an Asian girl able to sing the part. And at the very end, we found her. I was teaching her Sun and Moon, she was a little anticipating what she was about to sing. She had beautiful musical logic, so she sensed where the music was going. So of course, Lea is my favorite. Other wonderful singers performed the part of Kim – we have a Korean singer Sooha Kim, and Joanna Ampil. But Lea is special – she is so strong, gets through to your heart.

“Miss Saigon” – Lea Salonga as Kim / Photo credit by Joan Marcus

LM: What is your main requirement for the leading performers?

C-MS: I want to make sure that when people listen to my musical – they realize it lives and breathes and is not being performed in the very old-school opera-style type of way. That’s not interesting. That’s not musical theatre. I want people to follow the story and feel what the characters are experiencing.

LM: I wanted to ask you about the versions of Miss Saigon, produced in various countries. I know that sometimes the composers and lyricists, creators of shows, make certain adjustments when the show gets translated into other languages as well as presented to audiences of other cultures, for example, to fit their values and understanding. But you wouldn’t do that – you would keep the show exactly as it was originally intended. Is that correct?

C-MS: Of course. There should be no changes. Sometimes, for example in Japan, when you say thank you – there are way more words and syllables to express that than in English. If that’s the case, I add some notes to make it work musically. But the basic score never changes. Alain [Bоublil] approved the translations into other languages – it used to happen with operettas in the 1950s even. There are some beautiful translations out there.

LM: Several years ago, Miss Saigon went on a world tour. However, as far as I understand, the Covid-19 pandemic interrupted the shows. Is everything back to normal with the tour now?

C-MS: We have an ongoing tour of Southeast Asia. We reopened Miss Saigon at the Sydney City Opera House, this production went over to Melbourne, and Brisbane, and they are doing a tour of Southeast Asia now.

Since the latest Broadway revival (2017), the musical Miss Saigon began its world tour, which includes multiple countries in Southeast Asia. Even though Miss Saigon was performed in Thailand back in 2012, the country became one of the first places where the show began even pre-pandemic. Local media paid special attention to the story told in the musical resonating on such a personal level in the hearts of many Thai spectators. A wide public discussion unfolded, whether Kim was a “strong” woman who took action or a victim of war – and was simply unable to become part of the cruel civilized world and therefore perished.

Dedicated to the 30th anniversary of the musical, a special theatre for two thousand seats was arranged in Tokyo at the Imperial Theatre. However, the pandemic interrupted the run of the show. In various cities of Japan, the shows were resumed in 2022, for the most part, the spectators and media representatives accepted the show warmly, and spoke of the story “about veterans and their responsibility for leaving behind the dust of life, the Amerasian children…” as touching, extremely relevant “now that the tragedy of war unfolds in the world around us…”

It is obvious that the subjects of diversity between the Eastern and Western cultures, mixed marriages, and the fate of half-blooded children, “children of the streets” still concern the spectators of today. The attitude toward Miss Saigon in Asian countries – participants of one of the largest armed conflicts of the twentieth century – Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, which have already welcomed the musical or are just about to see it soon, would be interesting to analyze from the point of view of the common human values, which are a huge part of the story portrayed in the musical. In the person of Kim – the modern Cio-Cio-San – we see the collective image of hundreds of abandoned women with broken lives, which is relevant as it turns out even over a hundred and twenty years since the opera was written.

The musical Miss Saigon has already entered the top list of the longest-running Broadway shows (currently, it takes the 14th place), and will be remembered not only by the appearance of the “real” helicopter on stage, the three Tony Awards (received by the leading actors in the show – Lea Salonga as Kim, Jonathan Pryce as the Engineer and Hinton Battle – as John), endless disputes about its political incorrectness, resentment of the Americans of Asian background, scandals concerning the cast, but first and foremost, people will remember such musical masterpieces as: I’d Give My Life for You, The Movie in My Mind, Why God Why, Sun and Moon and others.

Miss Saigon – is a musical “about love, self-sacrifice, and cultural differences -” that is a common summary that we read in multiple publications over and over again. If we are talking about the plot – it makes sense. But this show cannot be taken down to the solely factual side of the story, which was told by the creators of the show so masterfully. Because this musical is a cultural and civilizational phenomenon, it can be appraised according to the tendencies of world development. There are only two successful Broadway musicals that can be attributed to this category: We Will Rock You and Miss Saigon. The first one of the two – We Will Rock You – warns mankind of what may happen if we allow mega computers and artificial intelligence to take over. And the second – Miss Saigon – condemns people to an endless Déjà vu if they don’t learn their most important lesson – to put a stop to all kinds of violence and inequality.

One wants to believe that a movie version of the musical Miss Saigon, which has been in the works for quite some time, will be released and the promises made by the stellar producer of the musical – Cameron Mackintosh – will come true. The movie will expand the audience, becoming accessible to spectators from a variety of countries, including former active parties in the military conflict in Vietnam. Perhaps, the musical Miss Saigon will receive proper sequels like Miss Kabul, following the hot spots that break out constantly around the world.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Lisa Monde.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.