This is PART 2 of the interview. To read PART 1, click here.

AB: What questions were you exploring through AIBO?

EP: The first question was, can an AI be fascist? The answer is yes. I answered it. I’ve gone on to give some keynotes around the world at engineering and human-computer interaction conferences about this. One of the keynotes I gave to a human-computer interaction conference was, “I Built a Sicko AI and so Can You.”

The second question, which I’m now going into in more depth for the new work I’m developing, was, can an AI have epigenetic or inherited traumatic memory? I think asking that second question for AIBO was a little too much at the time.

AB: How so?

EP: When the video, the glitchy video was displayed of AIBO trying to grab Eva’s last memory– I think it was too complicated for the audience to understand. The room turning red or green or yellow with AIBO’s emotions was okay, but the very final part was confusing for the audience. It was because I wanted to prove a point about that fact that you can create an emotional analysis of a fake emotional being. In that sense it was successful. I was able to analyze the fake emotions of a fake entity.

The reason why that’s so important – the issue of analyzing the fake emotion of a fake entity – is because AIs are going to control so many things within the next 10 years, including medical diagnostics, credit, bail, insurance, job interviews, even education. You know, so many things, and most people place their faith in that. The other thing is AI is now being used in certain countries that use deeply flawed systems of control to monitor the citizens of that country. It’s also being used to monitor students in certain school systems. The faith that people put into these structures is deeply misguided. That’s why I wanted to analyze the fake emotions of a synthetic being at the same time in relation to real human emotions, which you could see displayed on the performer’s bodysuit of light. You could actually witness the performer’s feelings live-time, they can’t fake it. If the performer got interested in something you could see it immediately on her body. It was a real emotion from a real person.

AI ABIO trying to emulate Eva’s last positive emotional memory (in tv screen) but failing. PC: Ellen Pearlman.

AB: Going back to this question of can AI have epigenetic memory, what are your thoughts on this after the performance of AIBO? There’s the issue of how this idea got translated, or didn’t, in terms of the audience. Did it bring up more questions for you?

EP: Yeah, that brought up a lot of questions for me. In preparation for that question, I first did an artist residency in St. Petersburg, in Peterhof outside of St Petersburg, Russia, which is where the Czar’s summer palace is located. I did nothing for a month but read on the history of genetics because I wanted to understand the beginning of epigenetic, or inherited traumatic, memory. Inherited traumatic memory is a change in the rDNA structure of the living entity. And there are many living entities which can have rDNA changes in their structure. This structural change is passed down through generations. It’s also nonverbal. It is the backbone running through of a lot of cultures of diaspora and trauma. Right now, to the best of my knowledge AI can’t touch it, doesn’t understand it, and doesn’t know how to quantify it. Quantification is about sorting and control, and AI is good at doing that. To ask the question if an AI can have epigenetic or inherited traumatic memory is going to be the focus of my investigations for the next two or three years. And it was just lightly touched upon in the AIBO opera.

AB: I want to ask about the process in working with your human actress who played the character Eva and working with the technology. I imagine that process must have been fairly unusual. Is she a trained actress originally?

EP: One of the other things I do is I’m a research professor in Latvia. In my master class I met a student who went out of her way to interview me. She was very, very enthusiastic. And she had dreadlocks, which is very rare for a young Latvian to be walking around with dreadlocks. She was a video editor. And I thought, you know, I bet she would want to do it. And I asked her, and she said yes. Once she was able to get funding to do it, she came to Estonia where I was developing the piece. It took me five months to train her over the course of a year including multiple trips between Estonia, Latvia and New York.

AB: Wow.

EP: I had to train her both how to move with a brain-computer interface on her head so she wouldn’t disrupt the signals, and how to somatize her movements so she was more focused on her body and wouldn’t get distracted. I had to rehearse the libretto with her at least 100 times. Keeping a headset on for 45 minutes is difficult because it’s like keeping a smartphone attached to your head for 45 minutes. You can imagine how exhausting that is. She tended to go into a state of indifference, which was read by the brainwave headset as a state of meditation. Her brainwaves became predictable, which is terrible for a brainwave opera.

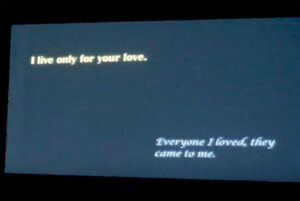

Because of that I had to train her when she spoke the libretto to become Eva and believe the things that Eva would say to her lover. She was not an actress or a performer. Because of that it took a great deal of work to get the full range of her emotions to appear. To do that I would let her watch her brainwaves change. She watched them as she performed. That was very helpful for her, because she could see the changes in the affect as she spoke. She began to see how saying certain words- and English was not her first language, saying certain words in a certain way with a certain kind of emotion would change her brainwaves, which would ultimately change what the audience could see and hear. I also let her listen to the different sounds that her emotions triggered. I let her see the different visuals that came up as she was speaking, so she had direct feedback. She learned, oh, if I emphasize this, the visuals change, my brainwaves change, and the sound changes. She began to learn how to act and say her lines by watching her actual biophysiological, sonic, and visual feedback.

Live time projected libretto. Eva’s libretto is yellow in the top left, AIBO’s libretto is blue, bottom right. PC: Ellen Pearlman.

AB: I’m thinking about what a bizarre introduction that is, for an actress’s first performance to have this direct brainwave feedback that is also exposed to the audience.

EP: Well, she immediately went back to video editing when the performance was over.

AB: (Laugh) Why do you think that is?

EP: Because she wasn’t an actress, and because she could make good money video-editing.

AB: Can you talk more about the team you worked with and the support you had?

EP: I was very, very, very lucky in that I went to a country with only 1.2 million people, which is Estonia. Estonia is part of the Baltics and is the most e-friendly country in the world. You can open an E-business in Estonia in just three hours.

I worked with the Human-Computer Institute at Tallinn University, and had the unbelievable good fortune to be invited by the Estonian Academy of Art to work in and on the premises of their newly refurbished art school. I was able to put together the smart textiles with a graduate student Dila Denmir as well as work with their technical director Hans Gunter Lock. Hans also taught music at the Estonian Academy of Music, so it became a consortium between three institutions in Tallinn. I’m very grateful to the Estonian people for the opportunity. The team I worked with– they were unparalleled. If you go to places that people are not banging down the doors to get into, you might have a better chance than if you always are aiming for the top venues.

AB: What has theater enabled you to do that you cannot do through other visual art forms?

EP: What’s really odd is I’m not a theatre person, which I completely admit. I started as a visual artist and writer. I use technology so my practice is also my research. For me the research importance and impact of these performances is profound, and I present the research all over the world as pure research.

Theatre – and I say thank you to theatre – enabled me to actually create an imaginary world live-time with audience interaction that proved research theories. It also took the audience to another place. I don’t know any other creative form that could do that. Visual art, possibly. Music, possibly. But they weren’t big enough to contain all I wanted to say. Opera, and operatic theatre, with its overblown, overarching, highly dramatic, and speculative nature is the only form that can hold these inquiries for any length of time and make them interesting. And I profoundly thank theatre and opera for it.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Allison Berkoy.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.