“What kind of service do submarines provide?” asks the machine’s captain, Ricky Martin. “Silent service” is the proper answer.

It is nearly the dénouement of Cayenne Douglass’s Maiden Voyage, and the Captain’s rhetoric encompasses this story beautifully. For what else could “silent service” symbolize than the historical plight of women?

Maiden Voyage is the story of seven attempting to thwart that silence, becoming the first women-only submarine mission in US Navy history. The Captain, Ace, Dot.Com, Sledge, Twinkle Toes, Scooby, and Esmeralda are locked in tight quarters for 70 days; each has something to prove, to themselves, to their compatriots, to their world. As the underwater days tick by, mechanical and relationship failure combine to craft the perfect storm. We, as spectator, are left to wonder if these women will make it out alive.

I wasn’t certain, before arrival, how the environment of a submarine would lend itself to the exploration of gender inequity. Perhaps it would be the inherent masculinity of a military vessel? Water as the giver of life, drawing parallels to womankind? Something animalistic in the oceanic descent? What was uncovered, instead, was far more grounding. Masculine military was not the main ingredient in this submarine adventure. Rather, Douglass pries into a topic often ignored in feminist circles: the desperation to prove feminine strength exposing internalized misogyny even within female-presenting bodies. Whether it’s queer rape culture embodied in Sledge and Scooby; domestic violence in interactions of the Captain, Dot.com, and Esmeralda; or religious trauma creating a rift between Ace and Twinkle Toes, the pressurization of a submarine acts as parallel catalyst for these women. After all, when one cannot get away from societal pressures or each other, isn’t it just a matter of time before explosion?

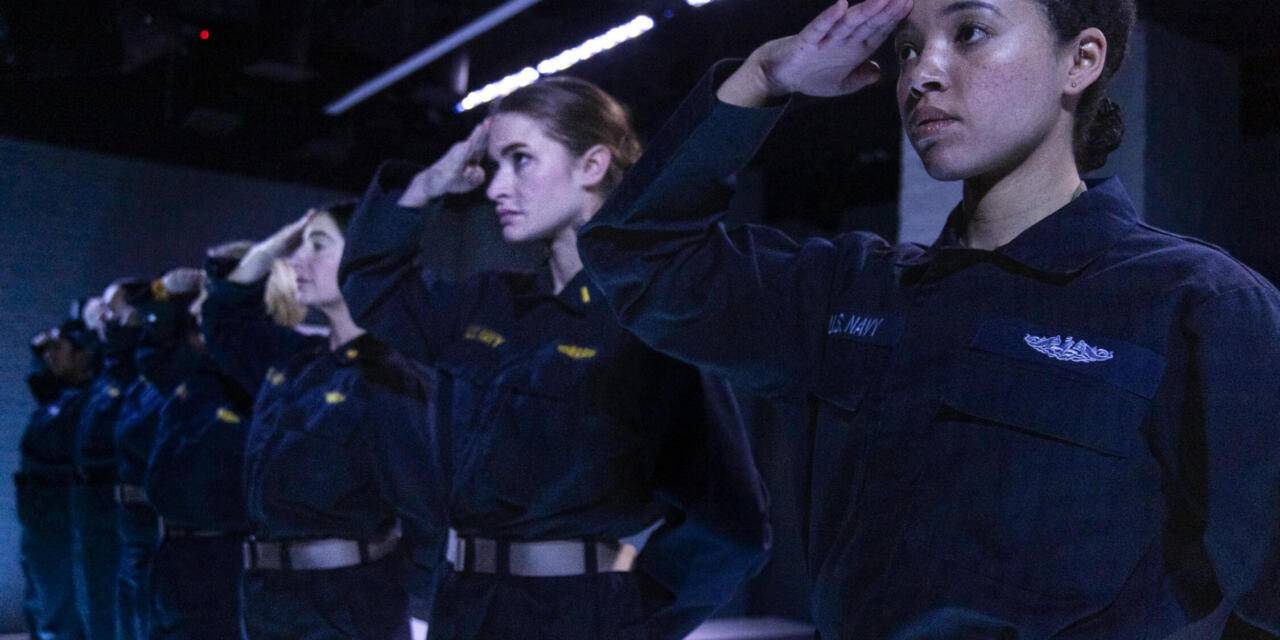

Arianna Banda (L) and Natasha Hakata in “Maiden Voyage.” PC: Bronwen Sharp

Maiden Voyage’s creative team clearly understood the task, striding masculine and feminine with ease. Set design by Frank J. Oliva was simplistic: the stage was composed primarily of grey, versatile blocks, punctuated by Mondrian-esque technical controls on either side; the effect was that of boredom and asylum. Elliot Yokum’s sound design and Taylor Edelle Stuart’s projections often married in a way eerie; as audience, I felt I was diving with the crew, felt the claustrophobia closing in around me. And there was a true creative star in John Salutz’s lighting design: utilizing color and aperture, the stage felt here expansive, there exhaustive, here vibrant, there sterile, making an altogether complex environment with little tools. The whole of the presentation was rather clever and compelling. I wasn’t sure if I would go mad or find rescue.

Line delivery matched the set’s cleverness: directed by Alex Keegan, the intercutting of duetted scenes and silent continuity made the audience feel as a fly on the wall. Keegan’s performers were naturalistic and grounded, compelling in their just being. Of particular note, I could not take my eyes off Natasha Hakata (Dot.Com) and Rachel Griesinger (Ace) whenever either entered stage. Hakata’s balance of maternity and badassery, of kindness and crushing verbiage, was achingly human; her engagement could not be matched. Griesinger’s capability of snark and witticism was equaled only by her vulnerability: I was touched by each scene she was in, a lover forced into a fighter’s body. Rounding out the cast, Tricia Mancuso Parks (Capt. Martin), Kait Hickey (Sledge), Georgia Kate Cohen (Twinkle Toes), Arianne Banda (Scooby), and Shimali De Silva (Esmeralda) delivered strong ensemble performances.

My only wish was for Act I to be as dramaturgically strong as Act II. The former felt like it’s still in its juvenile stage of development: while the characters are established with a firm hand, the pacing and tonality felt uncertain, a little stilted. There didn’t feel, to me, to be a climax or a catalyst prior to intermission. Relationship dynamic was semi-built as the audience watched these women’s daily lives, as was power structure outside of the military hierarchy. However, the written presentation itself felt dull compared to the sharpness of the second act. There, Douglass’s talent shone. The ebb and flow made perfect sense; relationships were dynamic and interwoven; individual internalizations were clear and wrenching; and there was proper drama throughout, making the ending a gut punch. If something similar were found for Act I, Maiden Voyage would be as near to perfect as one can get.

Rachel Griesinger (L), Tricia Mancuso Parks, Shimali De Silva, Kait Hickey, and Georgia Kate Cohen in “Maiden Voyage.” PC: Bronwen Sharp

To learn more about Maiden Voyage, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Rhiannon Ling.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.