Joe Klug is a gifted scenic designer who has a passion for reimagining musicals, particularly in intimate circumstances. When we met up to talk about the challenges of producing large musicals in small spaces, an unexpectedly delightful and philosophical discussion about design and practice took place. Although we had never met before, it was just like talking to an old friend, and so I have tried to preserve the conversational nature of our exchange. Here is what transpired:

Michael Schweikardt: What was the impetus of your interest in reimagining big musicals for small spaces?

Joe Klug: The impetus was largely practical. When you think of the ways that musicals have traditionally been produced you conjure up images of these large-scale, traditional, “wing and drop” shows. When I was a young designer just starting out, I soon discovered that many of the theaters that were hiring me to work on these musicals were unable to recreate them at that level. They either didn’t have the fly loft or didn’t have the wing space and they seldom had the budget. So naturally, the show had to be reimagined. Not to mention that the wing and drop style had become a relic of an older generation.

Michael Schweikardt: Agreed. And as much as I truly adore historic set designs, I don’t think that modern audiences want to be told a story in a style where the storytelling just goes on pause while we change locations. Our audiences crave something more cinematic, right? The gift is that we now get to create ways to continue the storytelling as a part of the scene change; the narrative never stops. Much of the fun for me as a set designer is figuring out how to continue to tell the story in the connective tissue between the scenes.

Joe Klug: Yes, figuring out how to connect the scenes cinematically while continuing the storytelling–those are some of the best artistic conversations that I have with a Director. Figuring out how to blend moments together, and what is important to see when leading out of one scene and into the next is so much fun!

I truly believe that audiences are craving something new. At the end of the day, everyone has seen the wing and drop version of these shows. They are classics and everyone knows how they function and how they were originally intended to move. It is now up to the next generation of theatre artists to rediscover the stories in these musicals and bring them to life on stage in a new way. Otherwise, they’ll turn into relics, or fossils on display like dinosaur bones in a natural history museum. It is our job as scenic designers to help the audience fall in love with these stories all over again.

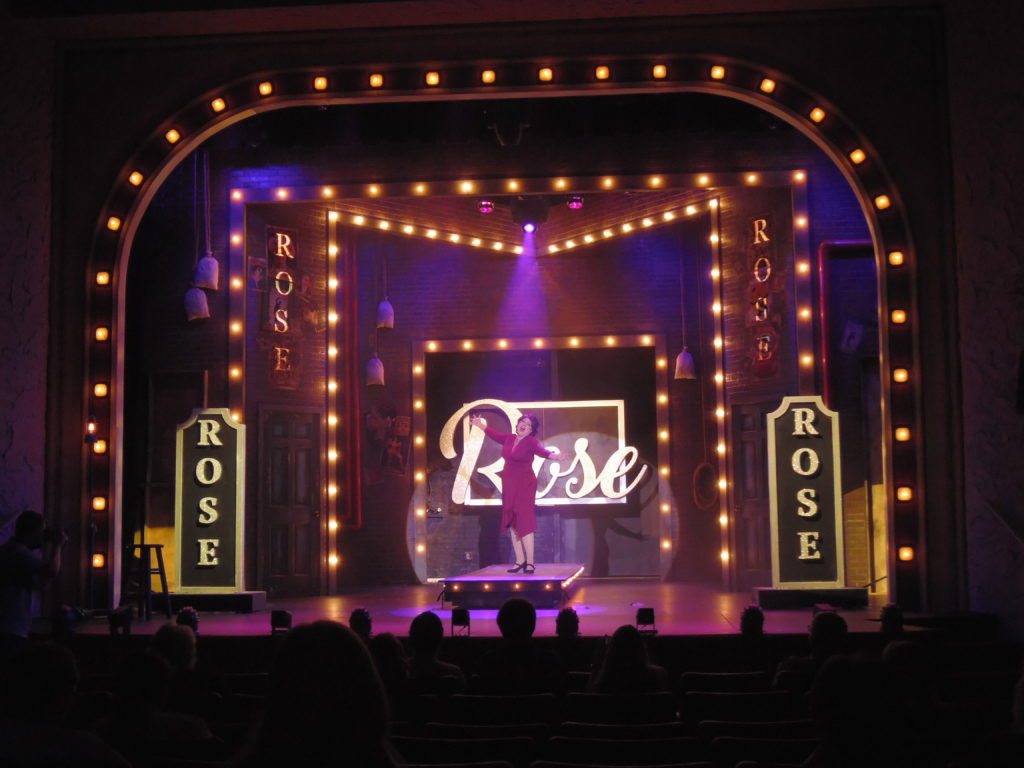

I always take a long, hard look at the story being told. What is their main goal? What are the key elements that are helping to drive the story forward? Once you answer those questions, things start to fall into place. For example, my Gypsy became all about Rose’s relationship to those around her. For me, it was less about various theaters and endless traveling and more about creating an environment where Rose’s larger than life personality would dominate and take over everything around her.

Gypsy, Garden Theatre. Directed by Tom Vazzana, Scenic Design by Joe C. Klug, Costume Design by Aj Garcia, Lighting Design by Alyx Jacobs, Sound Design by Jack Audent, Photo by Alesha Hollatz.

Michael Schweikardt: Gosh, I love Gypsy. It is quite an intimate show, isn’t it? Most of the scenes and songs consist of only two, three, or four people. With the exception of Louise’s big strip number in the second act, arguably, the Newsboys number is about as big as that show gets. I think it is sort-of misunderstood and mistakenly thought of as a splashy musical. But that is your point, isn’t it? What is the story? What is the story? What is the story? The more I ask this question of musicals, the more I find that even the largest of them has an intimate core. Showboat, considered by most to be an epic, can be reduced down to the story of the love that exists between the members a small, show-business family. If you concentrate on that story, suddenly it doesn’t seem so daunting.

Joe Klug: My goal with any musical is to find the intimate core. Strip away all of the added glitz of ‘Broadway’ and you’ll find that any musical can be produced on a small scale. You just need to figure out what makes it tick, what drives the story.

Here is another example: when I was Scenic Design Fellow at the Hangar Theatre in Ithaca, Jo Winiarski designed a stunning production of Titanic. I remember looking at that production in awe because It made me fall in love with the characters. To Winiarski, the production was about the people and their relationships. The ship was secondary to that story. This has stuck with me throughout my career. It has left an imprint on me that defines how I look at musicals.

What is the story? is the question that I will be trying to answer until the day I die. There is a TED Talk by Andrew Stanton, a writer for Pixar, that discusses the art of storytelling. One of the things Stanton focuses on is the idea that every character has a spine. In Finding Nemo, Marlin’s spine is to protect. In A Toy Story, Woody’s spine is to do what is best for his child. I think this concept applies to musicals. We have to ask what is the spine of the story. What is the driving force? For me, Gypsy is Rose’s story and everyone else is a supporting character. Rose’s driving force is to find success. She tries to find success through June until June leaves and then she tries to find success through Louise. What she doesn’t realize is that she could find success by simply marrying Herbie, settling down, and being a family. Ultimately, I think this is her tragic flaw.

When designing Into The Woods, the spine of the story became about the magic of books and storytelling and how they can bring people together. It became less about the woods and more about a storybook that comes to life–a magic landscape that allowed two-dimensional storybook characters who have a wish for themselves (I wish) to develop into three-dimensional people with a collective wish (we wish). This translated into a set that resembled an abandoned library where characters could literally jump out of the bookshelves and come to life; bookshelves opened to reveal characters; Little Red Riding Hood would open books and paper origami flowers would pop out; when the Giant stepped, the shelves would collapse and books would scatter across the floor.

Into The Woods, Garden Theatre. Directed by Steve Mackinnon, Scenic Design by Joe C. Klug, Costume Design by Aj Garcia, Lighting Design by Cedric Brown, Photo by Steven Miller Photography.

Michael Schweikardt: It sounds like it was full of surprises. I think that surprises that lead to delight are a key element in a set design. Perhaps as a designer, you can take an audience almost anywhere in the setting as long as the story and the action can play themselves out imaginatively in the environment you choose. What you describe in Into The Woods aren’t only beautiful images but they are also events–things that happen–and that’s a play, right?

Joe Klug: I agree. So much of set design is about creating events and moments. Steve MacKinnon directed Into The Woods–a lot of the work that I have done reimaging musicals has been with Steve at the helm. We had a lot of conversation about what these moments could be and many of the ideas came from Steve himself. He’d give me bits and pieces of it to run with, and then we’d come back together to refine and to continue to discuss ideas. It is this back and forth that creates a springboard to launch us forward. This push and pull drives the process and helps us bring something fresh, new, and engaging to the audience.

Michael Schweikardt: But besides these delightful moments of action that you and MacKinnon devised, there is a very big picture idea at work here too.

Joe Klug: Yes, I usually search for something, some idea, that can visually embrace the entire show. When I teach, I refer to this as the envelope and I ask “what is the aesthetic envelope that can hold the whole show together?” For Into The Woods the envelope was an abandoned library. For Once the envelope was the streets of Dublin.

When talking with the show’s director, Valerie Rachelle, we both knew that we did not want to set Once in a pub. It was expected. So the goal became to shape the landscape in a way that was unexpected but still supported the story of how music transforms and touches our souls. We ended up looking at the rich and lush textures of the streets of Dublin–the iconic brick and stone storefronts and the pops of color in the architecture. Ultimately, this was this landscape that felt right to us for a world where two young artists can meet on the street, share the music they create together, and fall in love.

Once, Oregon Cabaret Theatre. Directed by Valerie Rachelle, Scenic Design by Joe C. Klug, Costume Design by Lauren Blair, Lighting Design by Chris Wood, Sound Design by Graham Howlett.

Michael Schweikardt: Interestingly, I am also designing Once right now. Similarly, we don’t want to set the show in a pub. There’s nothing wrong with that idea. It worked well, but as you said, it is expected. So we want to do something else. We are also moving our production “outside” onto the street, but for me, it has become mostly about characters in a world that is incomplete so I am creating an architectural world that is unfinished or waiting to be finished or needing filling-in. It is all inspired by the community of buskers on Grafton Street in Dublin. We ignored the impulse to feel the show was somehow meant to be set in a pub. We looked to the script, it provided us with a story we wanted to tell and it pointed us to the scenic environment.

Joe Klug: When you look at the script for Once it becomes clear that it does not require you to set it in a pub. That was just one brilliant designer’s solution for the Broadway production of the show–one solution of many solutions that are possible.

Once, Oregon Cabaret Theatre. Directed by Valerie Rachelle, Scenic Design by Joe C. Klug, Costume Design by Lauren Blair, Lighting Design by Chris Wood, Sound Design by Graham Howlett.

Michael Schweikardt: I have this theory that famous musicals end up having their whole history of production attached to them, like moss growing on a stone over time and this creates expectations, certainly for the design, not to mention the performances. A great actor takes the role of Evita and strips away the history of production. They strip away the ghost of Patti LuPone and her performance and they go back to the story and build a new performance from the ground up, from ground zero, and the world takes notice. I try so hard to do the same thing when designing a classic musical. You can’t ignore their production history, right–or you do so at your own peril. So you have to be aware of history and yet, you have to be able to read the script as if it is a brand new play. If you go back to the story, to ground zero, you can build an original production and imagine it in any circumstance – small theater, in the round, on a $500 budget, whatever.

Joe Klug: It is interesting that you draw a comparison to performance. It is true that much like a performer playing Evita would actively work to make the role their own, the set designer should also work to make the design their own. I totally agree with the sentiment of removing the moss and peeling away the layers. But it is hard when with every collaboration comes this undercurrent of “well, this is what the Broadway production did.” It can drag you under.

Michael Schweikardt: So what do you do?

Joe Klug: Well, I think if you are going to break the mold, you need to do it responsibly, right? So on some level, you should take the time to understand the original production of a show so that you can make informed decisions about how you are going to deviate from it. Using the script, I break down the show into its basic building blocks–I deconstruct it and I study its architecture and I come to understand its DNA–and then I reshape it to fit me.

Michael Schweikardt: I want to talk about the concept of “less is more” and get your feelings on that phrase. Set designers hear this a lot, particularly when we are working in small spaces. I think, in general, I believe in that phrase. Anything that gets distilled, should by nature, become more potent and powerful. But I think we have to highlight the difference between ‘less’ and ‘distilled’. I recently designed a production of Oliver! and I was proud of the work but I couldn’t shake this feeling of dissatisfaction. The sculpture we made was beautiful and appropriate, but it never changed – it didn’t surprise. At one point in that story, Oliver gets out of the slums of London and travels to Bloomsbury, and there is an opportunity there, a need for the world to explode out of what has been and into something new, foreign, and delightful. Frankly, I’m not sure we spent enough money on that production to make this possible, or maybe we spent our money in the wrong places. Ultimately, someone intending a compliment said to me “less is more,” but in this case, less was simply less. Do you have any thoughts on that?

Joe Klug: It’s interesting that you bring this up. I had a similar experience this past summer. I designed a production of My Fair Lady and I also felt dissatisfied. I had distilled the production down to a handsome and functional unit-set that had furniture pieces that moved in and out to establish the individual locations. I remember at the time being very pleased with it until I saw the Ascot Tent Fly in around the performers. Once that happened, I realized that it didn’t move with Eliza’s journey; it didn’t transform as she grew. It was lovely and the director was pleased. It worked well for this particular production, however, in the end, I questioned if I had sacrificed some of the storytelling in my effort to make it more intimate.

When we distill down the scenery, it helps bring focus to the story that we are telling but, we are constantly walking a fine line. If we lean too far into minimalism we run the risk of not helping to move the story along its journey and if we lean too far in the other direction we run the risk of losing the story in a sea of stuff. It is a delicate balancing act.

Michael Schweikardt: How do you achieve that balance?

Joe Klug: In general, I begin by shaping the overall space, by shaping the envelope first. Once I feel that I have that general landscape pinned down, I will switch gears and begin to plan out how things will enter and exit the envelope and how things can shift and change the space from moment to moment. At this point, sometimes I discover that the general envelope is so large that there is nothing to help me move the show forward–it has gone out of balance. My first impulse is always to cut from the moving pieces, however, I have to check myself. I can’t allow the general envelope to completely take over and devoured all of my resources. So I am always checking the design to see if it is maintaining that balance. I am constantly looking at how the show evolves and breathes, how the scenery ebbs and flows, and attempting to make sure that it moves in a variety of ways so that things don’t become stale.

Michael Schweikardt: You can’t ever get complacent. You really have to constantly question your work and challenge yourself.

Joe Klug: When I was at The Hangar, Adam Zonder said to the design fellows: “Run at the wall at full speed. Sometimes you will hit the wall. Sometimes you will break through it. But when you break through it, it will be magical.”

Michael Schweikardt: Can you unpack that quote?

Joe Klug: The point is that you have to give it a try.

With My Fair Lady, I was ultimately dissatisfied with how the show moved and its lack of journey. However, I am not disappointed that I tried. I ran at that wall and in that case, unfortunately, I hit it. But when working on Into The Woods, and Once, and Gypsy, I broke through the wall and I was able to bring those stories to life in a new way.

At the end of the day, my job as a designer is to push the boundaries and to challenge the norms–to see how far a production can stretch. There is risk involved and sometimes a production is a success and other times a production is not. But I learn something new from each and every experience.

There are a magic and an excitement that comes from reimagining and reshaping musicals. I want to continue to explore. I am eager to continue to discover how musicals will evolve.

Big Fish, Orlando Repertory Theatre. Directed by Steve MacKinnon, Scenic Design by Joe C. Klug, Costume Design by Olivia Hayhoe, Lighting by Alyx Jacobs, Sound Design by Anthony Narciso.

Joe C. Klug’s scenic designs have been seen all across the country. Credits include Orlando Repertory Theatre, Milwaukee Repertory Theatre, The Summer Repertory Theatre Festival, The 6th Street Playhouse (Santa Rosa, California), Remy Bumppo Theatre Company, Music Theatre Works (Chicago), First Stage Children’s Theatre (Milwaukee), Bristol Valley Theatre Company, The Hangar Theatre (New York), The Mead Theatre Lab (Washington D.C.), Oregon Cabaret Theatre (Ashland), The Garden Theatre (Orlando), Illinois Shakespeare Festival, and Arkansas Shakespeare Theatre. He was recently selected as one of the designers for the USITT’s USA Student Exhibit for the 2015 cycle of the Prague Quadrennial; the international theatre design conference in the Czech Republic. Joe is an Assistant Professor in the School of Theatre, Film, and Television at the University of Arizona. He received his MFA in Scenic Design at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. In April, Joe was recognized by Live Design Magazine as a rapidly rising star in the field of scenic design and featured in an article 30 Under 30: Joe Klug, Scenic Designer.

https://www.livedesignonline.com/theatre/30-under-30-joe-c-klug-scenic-designer

Online portfolio at www.jckscenicdesigns.com

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Michael Schweikardt.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.