In an early scene of Rick Elice’s irreverent Peter Pan prequel, Peter And The Starcatcher, the precocious Molly Aster discovers three orphan boys in the bilge dungeon of the Neverland, a shabby merchant ship on an 1885 voyage from Portsmouth to the remote and dangerous isle of Rundoon. Upon her request for the leader, and without the consensus of his fellow orphans, the cocksure Prentiss introduces himself in charge. After a few more feeble assertions, including his claim that “The leader has to be a boy,” Molly turns to the timid, tubby orphan: “Ever notice, Ted—the more you claim leadership the more it eludes you?” Appreciating the sly put-down, from a girl no less, Ted shoots Prentiss a sideways glare and anachronistically retorts, “Oh, snap!”[1]

Staged by Tony-winning veteran actor Roger Rees and rising-star director Alex Timbers, Peter And The Starcatcher was developed over five years by Disney Theatrical Productions (where I have now been employed for a decade) in successive collaboration with Williamstown Theatre Festival, La Jolla Playhouse, New York Theatre Workshop, and a partnership of Broadway producers. The play was Disney’s best-reviewed project in The New York Times, surpassing even The Lion King. [2] It earned nine 2012 Tony nominations and took home five awards, including Best Scenic, Costume, Lighting, and Sound Design—a historic sweep. A darling of the New York theatre community, Peter And The Starcatcher became the longest-running play of the 2011-12 Broadway season, transferred off-Broadway due to continued demand, and booked a rare national tour, which launched in Denver to more critical acclaim in August 2013. But in the midst of this success, nobody besides industry insiders and scrupulous program readers knows that it is a Disney project.

Having taken Molly’s keen observation to heart before Peter And The Starcatcher came to New York, Disney Theatrical’s president and producer Thomas Schumacher made the prudent decision to keep “Disney” off the show’s title and its leadership low-profile. Due to the power of the Disney brand and the huge target of sometimes unwarranted criticism that our theatrical ventures had become, at least in New York, it seemed better to let Disney’s first play stand on its own and the Broadway credentials of its billed creators—Elice (Jersey Boys), Rees (Nicholas Nickleby), and Timbers (Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson)—draw ticket buyers downtown to New York Theatre Workshop in the spring of 2011. The strategy paid off. Positive reviews and sold-out houses ultimately carried the project to Broadway the following spring.

Peter And The Starcatcher: Off-Broadway Show Photos

https://www.broadway.com/shows/peter-and-starcatcher-offbway/photos/peter-and-the-starcatcher-off-broadway-show-photos/186041/show-photos-peter-and-the-starcatcher-cast

Despite its status as a relative newcomer to commercial theatre, with Beauty And The Beast premiering in 1994 as an experiment, Disney Theatrical has now become one of the industry’s most successful producers. Our shows, combined, regularly secure between 10 and 20 percent of the weekly Broadway box office, particularly during peak tourist seasons. The Lion King, which premiered in 1997 and won six Tony Awards, including two for director and costume designer Julie Taymor, became the highest-grossing Broadway show of all time in 2012, with over twenty global productions in eight languages to date. Only three of our eight Broadway ventures shuttered before recouping their initial investments—which is far below the 75- to 80-percent average commercial failure rate—but have since found profit in international and licensed productions. In just ten years, Disney’s catalog of over twenty titles for adult and young performers at Music Theatre International has generated over 50,000 licensed productions worldwide. And Disney’s partnership with Feld Entertainment brings the company’s characters, stories, and songs to millions of spectators in over 80 countries each year through Disney On Ice and Disney Live! touring arena shows. [3]

So, why the far-reaching success? It would be easy to chalk it up to the deep, family-friendly movie catalog and incomparable distribution machinery of one of the world’s largest entertainment companies. I will not deny that these elements provide a significant leg up for theatrical ventures—if they’re good. However, I will argue that Disney’s real, sustained success on stage stems from two essential elements: the core dramaturgical practice that leads the creative development and the careful curation of appeal. Ever since the brothers Disney founded their namesake company in 1923, character and story have been at the center of every film, book, series, park, and play. Decades of refined “storyboarding”—a process by which animators and writers map out a film with drawings and words then act out the story for producers before pen ever hits celluloid (or now, before pixels illuminate computer screens)—have invited critical feedback and clarified themes and emotional throughlines that might appeal to the widest possible audiences, not only in a specific place and time, but also for posterity. Although Schumacher and his producing partner Peter Schneider had worked many years in nonprofit and festival theatre before arriving at The Walt Disney Studios in the late 1980s, their time at Disney Feature Animation (now called Walt Disney Animation Studios) helped shape how they would lead commercial theatrical development when the opportunity presented itself just a few years later. Storytelling rigor would continue to be key.

One major difference between Disney Theatrical and other commercial theatre producers is that we develop all of our shows in-house with source material that the company already owns or acquires. Most shows come to Broadway after already establishing themselves as commercial hits elsewhere, usually London’s West End or at a regional nonprofit theatre, where commercial producers may or may not be involved from an early stage. These shows’ ticket sales must demonstrate potential to pay for weekly running costs and to pay back capitalization costs (underlying rights, rentals, developmental workshops, rehearsals, creative fees, etc.) with profits within a certain amount of time (usually 20 weeks for a play or a year for a musical) so that investors can eventually make money. Given that the vast majority of commercial theatre ventures lose money, there’s often not much difference between nonprofit “donors” and commercial “investors.” No matter the venue, rich people subsidize theatre tickets; on the rare occasion that a commercial show is a hit, the rich people get some of their money back. Disney works somewhat outside these two models since we are responsible to stock shareholders. We use their money to capitalize projects. If the projects become profitable, Disney returns the money to the shareholders in the form of dividends; if not, the company writes off the losses. Of course, Disney Theatrical’s annual profits funnel into The Walt Disney Studios, a major segment of The Walt Disney Company (which also comprises theme parks, media networks, consumer products, and digital interactive divisions), so it is difficult for the average shareholder to parse the theatrical contribution. However, our awareness of Disney’s fiduciary responsibility to shareholders affects the projects we tackle. Unlike independent commercial theatre producers, who are able to take on projects based on personal passions regardless of financial outcome (especially the wealthy ones), we can only invest time and resources into theatrical projects that have a reasonable chance of turning a profit.

Thus we enter the debate over appeal. For whom will a given show be created? In Hollywood parlance, the “big hits” address four-quadrant home runs: children, adults, female, male. On Broadway, female adults often drive ticket sales. [4] What actually appeals to them and the friends and family they bring along is the $100,000 question (or more like $15 million for an average new musical). To illuminate, I present the case of Newsies, Disney’s other recent unlikely hit, which picked up 2012 Tony Awards for Alan Menken and Jack Feldman (score) and Christopher Gattelli (choreography), along with six other nominations. Based on a 1992 musical film that was in turn based on the historical 1899 Newsboys’ Strike, Newsies was never intended for Broadway. Directed by Kenny Ortega, who later helmed Disney’s High School Musical mega-franchise, the film cost $15 million but only took in $3 million at the box office; however, on VHS and DVD, it became a cult classic for an entire generation of musical theatre fans. The title was on the top of MTI’s request list ever since Disney began licensing shows in 2004, but development on the stage musical, which could not seem to break free from certain of the movie’s cartoony and convoluted elements, was in limbo until Harvey Fierstein serendipitously ran into Menken at the grocery store. When the composer lamented Newsies, the veteran comic actor and book writer Fierstein, an unabashed fan of the movie, jumped at the opportunity to help out. With some streamlining and a few key character and plot changes, Fierstein’s fresh contribution was able to put the project back on track and free up Menken and Feldman to write new songs and revise others.

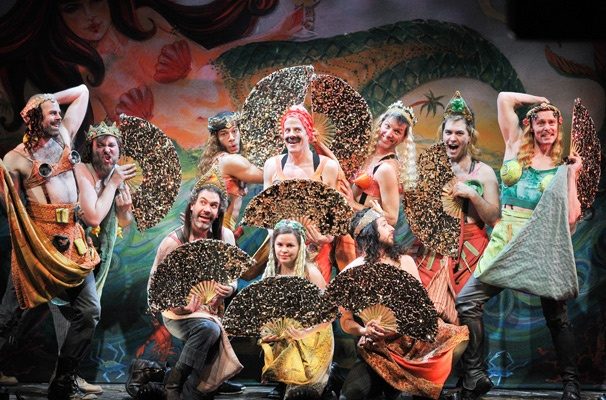

Newsies. Blog: Our Reality Show – Glenn Cook: Words, Photos

http://glenncook.virb.com/our-reality-show/tag/Newsies

Investing in our usual rigorous table work, we bent the script and score to a dramaturgically sound place. However, the developmental readings—which included fantastic new arrangements of fan favorites “Carrying The Banner,” “Seize The Day,” and “Santa Fe”—revealed that something was not quite hitting the mark. This was a dance musical and we had yet to see it move. Although Newsies was aimed solely at the licensing catalog, Schumacher decided to invest in a one-off production with a top-notch creative team before we settled on the final version of the musical that would be done in high schools across the country. Paper Mill Playhouse in Millburn, New Jersey, stepped up to co-produce this pilot, and Jeff Calhoun, with whom we had developed and launched a successful stage version of High School Musical, agreed to direct. He and set designer Tobin Ost, along with projectionist Sven Ortel, created a modern unit set of three three-tiered swiveling towers that resembled fire escapes and could be decorated to evoke 1899 New York City. Gattelli, a former chorus dancer whose peers were in the movie, practically begged to choreograph. Filling out the creative team was veteran costume designer Jess Goldstein, lighting designer Jeff Croiter, and sound designer Ken Travis. The enthusiasm of the team quickly spilled over into auditions, with an unprecedented turnout of fine young dancers, including scores of working Broadway veterans who were willing to give up their steady jobs for a chance to be in this regional production Newsies. Up-and-coming stars Jeremy Jordan and Kara Lindsay landed the lead roles of union leader Jack Kelly and reporter Katherine Plumber, Fierstein’s conflation of two characters from the movie.

Although the young cast was enthusiastic beyond measure and took quickly to Gattelli’s exuberant choreography in studio rehearsals, it was not until we got on stage at Paper Mill that we realized the potential of Newsies to go further than we had expected. Cast energy, exuberant dancing, impressive scenography, a soaring anthemic score, and a story of young striking workers that resonated with the 99% in the midst of the Occupy Wall Street movement created a whole that far surpassed the sum of its constituent parts. We had been bracing for negative responses from cult fans (“Fansies”) since we had significantly altered the film’s story, as well as critics, who came from New York City with pencils sharpened (especially with “Disney” over the title of this show). To our pleasant surprise, the disarming musical registered approval at almost every turn, and speculation about a Broadway transfer spread quickly. [5]

Back in New York, the Nederlander Organization approached Schumacher with an offer of the vacant Nederlander Theatre on 41st Street, which is in clear view of the Disney Theatrical offices atop the New Amsterdam Theatre across the street. Not wanting to promise theatergoers anything on the level of The Lion King or Mary Poppins in terms of spectacle, Schumacher agreed to bring Newsies to Broadway for an unprecedented (for us) limited run of twelve weeks the following spring. (Coincidentally, we had already agreed to let a consortium of producing partners transfer Peter And The Starcatcher to Broadway the same season, and opening nights ended up just two weeks apart. Lighting designer Jeff Croiter and I ended up doing a lot of shuttling between the Nederlander and the Brooks Atkinson Theatre on 47th Street, as we were working on both shows—admittedly, a good problem to have!)

With dates set, we went to work analyzing what worked at Paper Mill and what we could improve before Broadway. Everyone agreed that the cast, set, and score cornerstones checked broad “appeal” boxes, so we just needed to focus on some of the minor elements that could better support the show’s highlights—what made people come and say “wow.” Menken and Feldman went to work on new songs for the villain Joseph Pulitzer and the sympathetic burlesque star and theatre owner Medda Larkin. Ann-Margret had played the role in the film, and we had cast a fantastic actress, Helen Anker, in that vein for the Paper Mill production. However, on Broadway, Disney had become known for its diverse casting practices and even won a national award for its multiracial casting of The Little Mermaid in 2008. As good as the Newsies cast was, we realized that it was not visually reflecting the complexions of 1899 New York, much less those of today. A bit of research revealed that black entertainer Ada Overton Walker, wife of vaudeville star George Walker, was a rising influence in her own right at the turn of the twentieth century. She became the model for a reconceived Medda Larkin, whom African-American performer Capathia Jenkins ultimately played on Broadway. Diversity also broadened as we added three alumni from the television competition So You Think You Can Dance to the cast. Not only were they phenomenal dancers, but also their national exposure appealed to nontraditional ticket buyers. During a short re-rehearsal process, new songs were inserted, prudent script and score edits were incorporated, and new cast members were brought up to speed. We opened on March 29 to fairly positive reviews. [6]

But the show had already become a hit before opening night. Newsies cult mania, combined with very strong word of mouth from Paper Mill, went viral online. It led to ticket sales from all fifty states and exhaustion of inventory before the first preview. Due to overwhelming demand, the run was extended ten weeks. Then, even before summer arrived, sales pressed the show into an open-ended run. Nobody saw this coming. Company management had to work quickly to extend contracts or find replacements for those who had already lined up other work after the initial contract date. Within forty weeks, Newsies became Disney’s quickest-recouping Broadway show. [7] While there are a few more dramaturgical tweaks I would love to make for the musical’s next iteration (there always are), I fully recognize that Newsies is working—really working—in ways that transcend dramaturgy. Paying careful attention to appeal is absolutely essential for a shot at commercial success, and my job depends on shows that make money. We can have the most dramaturgically sound show on the boards, but if nobody wants to see it, what difference does it make? Examples abound of terrific theatre that could not find an audience to support a commercial run. In most of these cases, essential appeal was not identified or developed sufficiently for the market.

Our theatrical work is unusual within The Walt Disney Company. Unlike films or toys, our products are live and repeated, and as such can evolve over time. Since we have a dramaturgical forum at our core and multiple distribution options, we are able to go back to the drawing board on shows whose first iterations do not fully succeed. For example, we have created new versions of Tarzan and The Little Mermaid, which fell short on Broadway, that have found success in international and licensed productions. And even hit shows can get better. In 2009, we cut twelve minutes from The Lion King for the musical’s premiere in Las Vegas and subsequently incorporated the successful cuts into productions around the world. Radically shorter versions of the show for young performers are being developed to join fifteen other titles in our Broadway Junior collection, which we create to help inspire the next generation of theatre-makers. [8]

The Lion King. Walt Disney Studios. http://www.waltdisneystudios.com/disney-theatrical-group/

During their tearful farewell on the newly christened “Neverland” island, the already-growing-up Molly and the now-eternal boy Peter attempt to remember all the details of their awfully big adventure, even playfully swapping lines from one poignant exchange: “PETER: And you’re the better leader. MOLLY: Really? PETER: No. (They laugh, enjoying each other. Then it changes.)” [9] As we revisit and reshape familiar shows, new projects with new rules—like Peter And The Starcatcher and Newsies—reinvigorate the Disney Theatrical horizon and challenge us to become better leaders, especially when we (mistakenly) think that we have got it all figured out. Key dramaturgical questions of “why?,” “why now?,” and “for whom?” lead our constant pursuit of appeal to an ever-evolving demographic of theatergoers who desire high-quality family entertainment.

The original version of this article, Intercultural Dramaturgy: Dramaturg as Cultural Liaison, was published in The Routledge Companion to Dramaturgy. Reposted with permission.

Notes:

[1] Rick Elice, Peter And The Starcatcher: The Annotated Script Of The Broadway Play (New York: Disney Editions, 2012), 29.

[2] New York Times chief theatre critic Ben Brantley raved about the play both at New York Theatre Workshop (“Peter Pan [the Early Years], With Bounding Main and All,” March 9, 2011) and on Broadway at the Brooks Atkinson Theatre (“Effortless Flights of Fancy,” April 15, 2012).

[3] Since October 2008, when Disney Theatrical Group moved its headquarters to the “open office” environment of the renovated Rooftop Theatre above the New Amsterdam Theatre on 42nd Street, Schumacher has actively encouraged pragmatic transparency about our diversifying work—while avoiding unnecessary fanfare. See, for example, Gordon Cox, “Disney Theatrical mixes it up,” Variety, March 17, 2012, and Patrick Healy, “Disney Shows in Development,” The New York Times, June 20, 2013.

[4] According to The Broadway League’s 2011-2012 demographics report, two-thirds of the Broadway audience is female. http://www.broadwayleague.com/index.php?url_identifier=the-demographics-of-the-broadway-audience, viewed September 2, 2013.

[5] Even The New York Times was welcoming to Disney’s Newsies “out of town”: David Rooney, “Newsboy Strike? Sing All About It,” September 29, 2011.

[6] Alas, once Newsies was on Broadway, Ben Brantley proved to be a less enthusiastic New York Times review than Rooney (“Urchins With Punctuation,” March 29, 2012).

[7] For more details on this unusual project, see Newsies: Stories Of The Unlikely Broadway Hit, edited by Ken Cerniglia (New York: Disney Editions, 2013).

[8] Descriptions of all stage titles in the Disney catalog can be found at www.disneytheatricallicensing.com.

Ken Cerniglia is dramaturg and literary manager for Disney Theatrical Group, where during the past decade he has developed over forty shows for professional, amateur, and school productions, including 2012 Tony Award-winners Newsies and Peter And The Starcatcher. He has written articles for numerous publications and recently edited Peter And The Starcatcher: The Annotated Script Of The Broadway Play (2012) and Newsies: Stories Of The Unlikely Broadway Hit (2013). The co-founder of Two Turns Theatre Company and the American Theatre Archive Project, he holds degrees in theatre from UC San Diego, Catholic University of America, and the University of Washington.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Ken Cerniglia.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.