This article was originally published as ‘Introduction’ to the edited collection entitled Contemporary Portuguese Theatre: Experimentalism, Politics And Utopia [Working Title] (edited by Rui Pina Coelho). Lisboa: Teatro Nacional D. Maria II / Bicho do Mato, 2017. We are grateful to the publisher for granting us permission to re-publish this article.

The notable history of theatre in Portugal, throughout the entire 20th century and on into the 21st, has created rather propitious conditions for shaping an artistic scene that is unabashedly open to experimentation, resolute in terms of politics, and adamantly driven by utopia. Thus, we will argue that experimentalism, politics, and utopia effectively serve as some of the most visible and permanent narrative axes for tracing the evolution of the theatre in Portugal from the early 20th century to more recent contemporary Portuguese theatre.

This alleged experimentalism will, of course, signify many things over the years. Up to the 25th of April 1974, the date that saw the end of the Fascist dictatorship which had governed Portugal since 1926, experimentalism would mean the attempt to more closely resemble the modern practices seen elsewhere in the European theatre. But the context of theatre in Portugal–dominated at the time by commercial theatre content and heir to a logic of theatre based on a star system coming from the death throes of the romantic tradition–would come to impede these attempts at proximity and relegate them to ephemeral, fleeting moments. Following the Carnation Revolution and the consequent establishment of the independent theatre (begun in the 1960s), a movement profoundly marked by a combination of Brechtian and neo-realist theatre, experimentalism would frequently be equated with formalism and thus avoided. But with revolutionary fervour subsiding and with greater independence gained from the pressure of box office receipts as more regular financing was being awarded to culture and greater freedom from State intervention, theatre in Portugal had then acquired its own space and was at liberty to create a theatrical scene immensely permeable to new forms and processes of a more experimental nature.

Politics has always been, necessarily, one of Portuguese theatre’s most worrying refrains. This is understandable for a theatrical context which had been under the yoke of a Fascist regime for approximately 40 years, and which later was called upon to play a pivotal role in the process of learning the concepts of democracy, in the construction of civic consciousness, and in overcoming Portuguese culture’s backwardness. If during the Estado Novo any expression of politics was surveilled, the arrival of democracy was accompanied by a theatre which celebrated the revolutionary and democratic ideals. With the gradual establishment of a more tranquil society and the advent of improvements to the basic conditions of life, political statements, on one hand, began to take on more abstract and philosophical heft, or on the other hand, were replaced by more worldly interests. Portugal’s accession to the EEC–European Economic Community (1986), together with the country’s first absolute parliamentary majority in 1987 which came with the election of the right-wing Social-Democrats led by Cavaco Silva, marked a new defining moment for the theatre fabric in Portugal. An authoritarian governmental policy giving top priority “to anything built with cement” before paying attention to immaterial matters such as education and culture led to a reengagement with political matters on Portuguese theatre. The rhetoric was, then, more distant, elaborate and complex, but still present and current. Even though the country benefitted from a notable investment in culture during the first years of the new millennium (2000-2006) from the Operational Programmes for Culture (POC) within the Community Support Framework for Portugal, the sector never really enjoyed sufficient financial comfort to approach theatrical activity with the necessary level of maturity. During the years of the Passos Coelho government (2011-2015), and the country this time under the yoke of the economic crisis and austerity imposed by international financial regulatory measures which led to the disappearance, suffering, and demise of many structures, theatre arts in Portugal saw how the subject of politics would rise once again with extreme vitality.

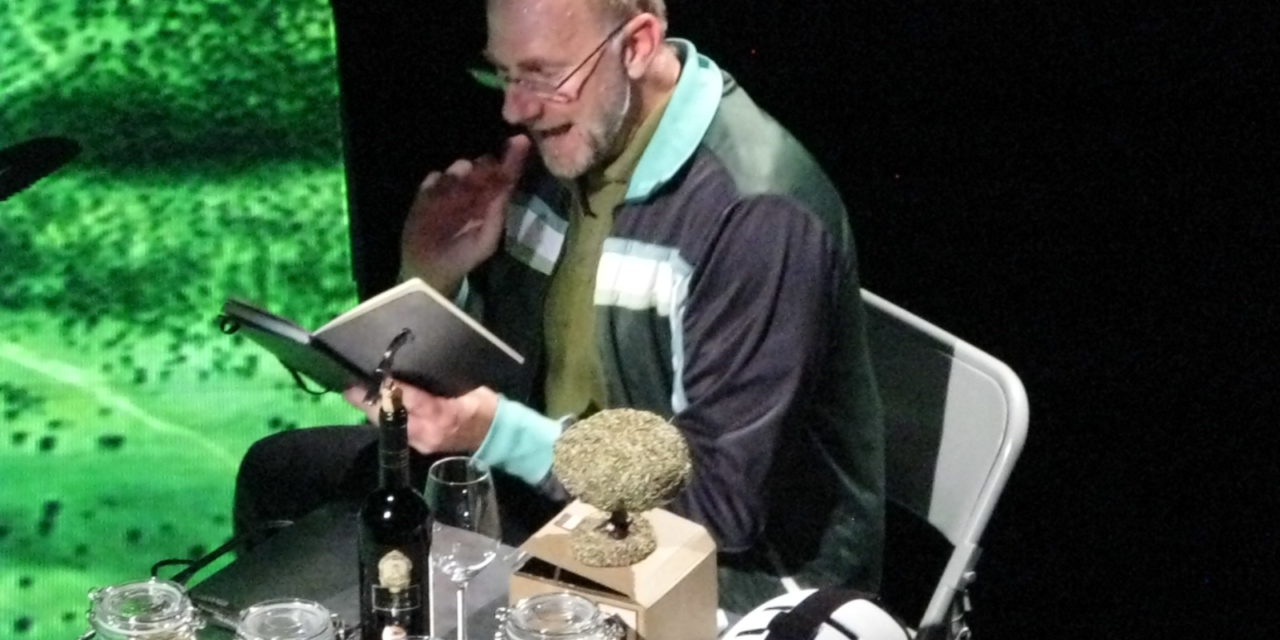

Mochila, by Gonçalo Amorim, Jorge Louraço Figueira and João Miguel Mota from April 6 to 8, Municipal Theater Constantino Nery, Matosinhos

Utopia has also always framed the enterprise of the theatre in Portugal. Such is not surprising: Portugal was a country off the beaten track and submerged in Fascist ignorance for nearly the entire 20th century; a country alienated from the most substantive aesthetical revivals in the Western theatre during this period and spoken of in a language of universal charm but removed from the most influential international circuits. Therefore, utopia has always been an absolutely indispensable element. Thus, the search for a theatrical aesthetic in tune with the European tempo, coming from a democratic, free, and politically conscious country reclaiming its theatrical art as an instrument for edifying the civic, moral, and aesthetic sensitivities of its citizens, has always been in utopian transformation.

These three narrative axes, each one inextricably linked to the other, aid in rephrasing the history of theatre in Portugal from the outset of the 20th century to the new millennium, and in these experimental, political, and utopic entanglements is uncovered the fabric which helps to characterize contemporary Portuguese theatre. The curious circumstances of Portuguese stagecraft and the history of free theatre, art theatre, experimental, alternative, or independent theatre (depending on the epoch in question) has been under construction since the early 20th century. Striving from the beginning to break with the logic and dominance of a theatre ruled above all by commercial interests and mass-appeal repertories, the 20th century opened with the foundation of initiatives whose clear intention was to renew the theatre and uphold Republican ideals, inspired by André Antoine’s Théâtre Libre and his naturalism of social nature: the Teatro Livre (1904) and the Teatro Moderno (1905). In both groups, the key element was Araújo Pereira, considered by many to be the first Portuguese modern theatre director; however, these theatres would sadly be short-lived. The Teatro Livre lasted only from 1904 to 1908, presenting performances merely during the summers of 1904, 1905, and 1908; the Teatro Moderno, founded in 1905 following the departure of Araújo Pereira and Luciano de Castro from the Teatro Livre, lasted no more than one season. These were projects which, although in tune with some of the theatre revival taking place across Europe, could not find fertile ground in Portugal at the beginning of the century.

Even more lesser-known and ephemeral than the two previous theatre groups was the Teatro da Natureza under the direction of Alexandre de Azevedo and Augusto Pina, equally sympathetic to the same spirit of cultural revival, which in June 1911 produced a series of open-air performances in the Jardim da Estrela.

Sewing Songs And Stories, by Taleguinho (Photo: Sara Reis)

Notwithstanding these endeavors, theatre in Portugal would continue to be largely dominated by commercial offerings, saturated with French comedies of proven success and with sugary versions of universal classics. Twenty years after the brief existence of the Teatro Livre and the Teatro Moderno, there was still precious little on Portuguese stages that posed an alternative to the still very deep-seated theatre paradigm of the time.

However, in the 1920s, signs of change were starting to be felt. Afonso Gayo, in Evolução do teatro português contemporâneo [The Evolution of Contemporary Portuguese Theatre] (1923), a conference held on March 25, 1923, at the Sociedade Nacional de Belas Artes [National Society of Fine Arts] concluded that “We are on the eve of a resurgence in Portuguese theatre” (Gayo, 1923: 6). This resurgence was noticeable to Gayo due to several factors: the organization of the Teatro Nacional, the construction of new theatres, Portugal’s signing in 1911 of the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works (from 1886), appeals in favour of original plays, and the influence of repertories from foreign companies performing in Portugal.

Amongst these significant signposts of change was the establishment of two important theatres: the Teatro da Juvénia–Escola Teatro (1924) directed by Araújo Pereira and the Teatro Novo (1925) founded by António Ferro. In 1924, Araújo Pereira, collaborating with César Porto, inaugurated the Escola de Teatro, also known as the Teatro Juvénia. Its pedagogical and artistic approach, determined by his Republican, socialist and progressive convictions, would represent a bold contrast to the prevailing attitudes in Portuguese theatre. A man of firm reputation in the theatre, Araújo Pereira focused on training actors to shun the vices of the acting profession; basically, he sought to create actors for the new theatre. At the end of the performances, for example, applause was not permitted, nor could mention be made of the actors’ names in the press, as this would prevent the seed of vanity or pretentiousness from being planted. The Teatro Juvénia was one of the collectives that most clearly advocated the need for a more demanding theatre, one whose only objective was not simply to please the masses or to satisfy the commercial interests of theatre impresarios. This socialist ideal embedded in theatre, however, would not survive the military coup of 1926.

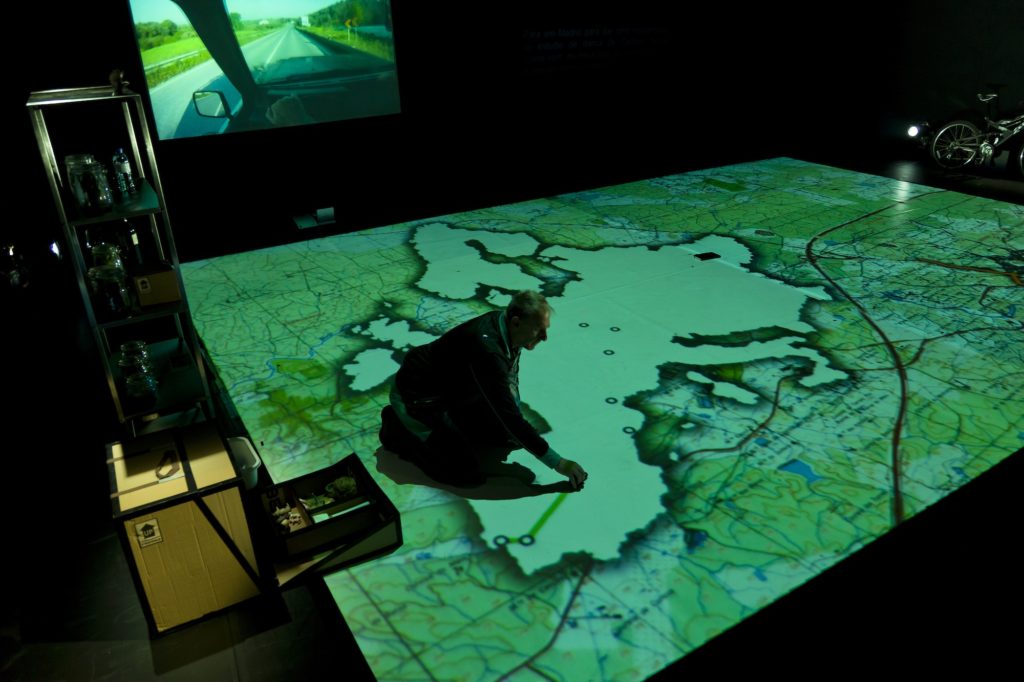

Rui Horta talks about the importance of losing oneself. To make the loss a method, especially when the experience of life tends to become a weight that leads us not to risk. The loss, then, as a method.

The Teatro Novo (1925), with its radically diverse political profile, was founded by António Ferro, who would later become Director of the Secretariat for National Propaganda during the Estado Novo, and José Pacheco. It was decidedly in line with theatre arts practices similar to those at other European theatres and focused on modernizing Portuguese stagecraft in terms of European standards, namely those in France. They would nevertheless produce only two plays – Uma Verdade Para Cada Um [Each In His Own Way] by Pirandello and Knock Ou O Triunfo Da Medicina [Doctor Knock, Or The Triumph Of Medicine] by Jules Romains–given that they only existed for approximately one month, controversial and incongruent as it was.

The nationalist and anti-parliamentary military coup of May 28, 1926 that would supplant Portugal’s First Republic, install a military dictatorship (later to be transformed into the fascist Estado Novo following the adoption of the Constitution of 1933), and require prior state approval of theatre performances, would effectively put an end to any fledgling attempts at experimental theatre.

The history of theatre deemed “experimental” in Portugal would only return to having any continuity in the period immediately following World War II. Given the defeat of the fascist German-Italian axis, the tight grip of Salazar’s censors began to slacken from 1946 to the early 1950s, which ushered in a period that can be characterised by the yearning for revival and greater closeness to the more modern currents and theatrical trends in Europe, marked by a still timid experimentalism that would inaugurate a new chapter for Portuguese theatre. This “experimentalism,” however, would not correspond exactly to the same practices of stagecraft that would be called experimental in European theatre elsewhere across the continent at the time. Instead, it would essentially correspond to the rejection of commercial interests and obsolete conventions of the acting profession, finding the tutelary example in the lesson from Jacques Copeau: a theatre centred on the actor’s physical expressiveness; a theatre of a humanistic dimension with lofty aesthetic values; a theatre of art which disdains the artistic concessions made for the sake of commerce.

Thus, groups formed to flesh out a type of “experimental movement,” comprising separate and short-lived enterprises constituted by amateurs or young actors in training. These attempts would not, however, reach out outside the stronghold of the shrinking class of intellectuals in Lisbon or Oporto. On this list were theatres such as Teatro Estúdio do Salitre (1946), Companheiros do Pátio das Comédias (1948); Manuela Porto’s Grupo Dramático Lisbonense (1948-50), Pedro Bom’s Grupo de Teatro Experimental (1951); Fernando Amado’s Casa da Comédia; Teatro Experimental do Porto (1953) and Teatro d’Arte de Lisboa (1955). Although we may recognize similar aims and a common context in this set of theatrical undertakings, each one of them had an individual profile.

Theory of The Three Ages S of Sara Barros Leitão June 18 and 19, Teatro Municipal Rivoli, Porto

The inaugural moment for this new chapter in theatre Portugal was April 30, 1946, the debut of the first performance produced at the Teatro Estúdio do Salitre, a group run by Vasco Mendonça Alves, Luiz Francisco Rebello, and Gino Saviotti, a whimsical assemblage made up of “conservatives and avant-gardists, monarchists and republicans, Catholics and Marxists, critics and creators, students and professors” (Rebello, 1996: 14) who would gather in protest against the stagnation and the systemic backwardness found in Portuguese culture. At the premiere of the first performance, a document called Manifesto Do Essencialismo Teatral [Manifesto Of Theatrical Essentialism] was read and distributed in which twelve points conveyed and explained the theatrical ideals that the group upheld, which defended a theatre that could present itself as a collective phenomenon freed from the dictates of the naturalist stage, the compulsory themes taken from the institution of theatre as social art, and the excesses and abuses of interpretative staging choices and the impositions of the apparatus of theatre. This “essentialist” theatre, in the singular rhetoric at the Salitre, echoed Copeau’s teaching in a notable way. Between 1946 and 1950 seventeen plays were performed, not all of which conformed to the group’s initial intentions, but in the end, they played a decisive role in the dissemination of new playwriting, new authors, and a new way of understanding the workings of theatre.

Pátio das Comédias, a name which later changed to Companheiros do Pátio das Comédias, in 1949, when it went professional, was founded by a rally of intellectuals and artists that included António Pedro, Jorge de Faria, Adolfo Casais Monteiro, Jorge de Sena, Luiz Francisco Rebello, José Blanc de Portugal, and José Augusto França (later joined by Costa Ferreira, Armando Ventura Ferreira, and Tomás Ribas, among others). It would be in the context of the activity of the Companheiros that António Pedro–one of the most important figures in this period and one of the most prominent theatre promoters and ideologues–would sign his first stage production.

Grupo Dramático Lisbonense (1948-1950), an amateur group led by Manuela Porto, was mostly comprised of members of the Fernando Lopes Graça’s choir, which essentially brought together young activists from the Movimento de Unidade Democrática [Movement for Democratic Unity] (MUD), which combined its artistic interests with a clear civic and political expression.

Pedro Bom’s Grupo de Teatro Experimental was founded in 1951 following the last performance occurring at the Teatro Estúdio do Salitre. Witnessing the end of this laboratory theatre and wanting to preserve the work which this collective was dedicated to, Pedro Bom carried on with the Salitre’s experimentalist adventure but in a new context.

The Casa da Comédia, an amateur collective which originated in the theatre section of the National Centre of Culture (CNC), presented two plays to the public, one in June 1946 and the other in May 1947, both at the Teatro do Ginásio. They reappeared approximately twenty years later (in 1962), again under the name of Casa Da Comédia and led by the same director, Fernando Amado, yet this time with their own space and a relatively stable cast of amateur actors.

Teatro d’Arte de Lisboa, founded a bit later than the previous groups in 1955 and run by Orlando Vitorino and Azinhal Abelho, was characterized above all by a certain cultural rigor in their selection of repertory and their philosophical penchants, and in their approach to dramaturgy.

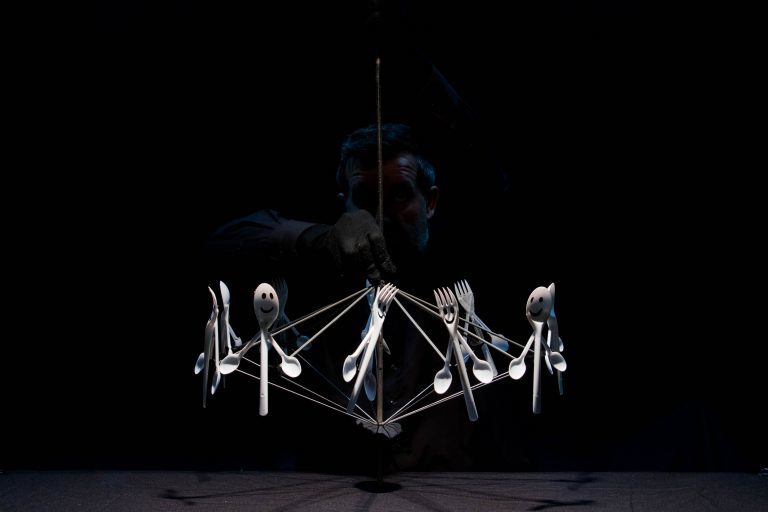

Objectsphere, by the Fair Puppets

All these initiatives and theatre collectives would end up foundering due to the imperviousness of the professional theatre fabric, which balked at any proposal that suggested a more experimental nature. All except one: the Teatro Experimental do Porto (TEP). Founded in 1953 within the framework of a “theatrical culture association” (the CCT – Círculo de Cultura Teatral), the group was amateur in its early years and later turned professional in 1957. Active still in the present day, TEP was the collective which served as the standard-bearer for experimentalism in Portuguese theatre in the 1950s. From 1953 to 1961, António Pedro served as Artistic Director and was responsible for turning the TEP into Portugal’s foremost theatre for modern stagecraft and for a repertory both congruent and appropriate for its theatrical time.

Mention should clearly also be made of the experiences and contributions of university theatres which, together with amateur theatres, were veritable bastions of theatre revival. Groups such as the TEUC–Teatro dos Estudantes da Universidade de Coimbra (1938), TUP–Teatro Universitário do Porto (1948), CITAC–Círculo de Iniciação Teatral da Academia de Coimbra (1954), the Grupo Cénico da Associação de Estudantes da Faculdade de Direito da Universidade de Lisboa (1954) and the Grupo de Teatro da Faculdade de Letras de Lisboa (1964), provided the necessary laboratory for experimentation and the application of the values of theatre revivalists such as Paulo Quintela, Luís de Lima, Victor Garcia, Ricardo Salvat, Juan Carlos Uviedo, Adolfo Gutkin, and António Pedro.

Also of important note are some of the efforts to bolster Portuguese theatre in its pursuit of novelty and experimentation as shown by the company Rey Colaço/Robles Monteiro, the resident company at the D. Maria II National Theatre from 1929 to 1964 whose attempt to stage Mother Courage by the banned playwright Bertolt Brecht in 1955 is but a simple example. Or the activity of the TNP–Teatro Nacional Popular (1956-69), directed by Francisco Ribeiro, an initiative also characterised by an atmosphere of theatrical rigor and by a practice of stagecraft more conducive with the theatre of his time–although this theatre was subject to a different framework given to the circumstances that obliged it to observe an official profile more in line with the Regime.

In general terms, it was also these ideals of intellectual thoroughness and artistic rigor that would come to motivate the Teatro Independente, which began in the 1960s, at a time coinciding with the colonial wars, student unrest on university campuses, and waves of emigration which saw thousands of Portuguese leave their own country.

The Teatro Moderno de Lisboa–Sociedade de Actores, operating from 1961 to 1965, is frequently viewed as a precursor to the independent theatre movement in Portugal. Many of its founding members, (Carmen Dolores, Armando Cortez, Fernando Gusmão, Rogério Paulo, and Armando Caldas), having begun their careers in post-war experimental groups or having been part of the regular cast at Francisco Ribeiro’s Teatro Nacional Popular over the years, found in the Teatro Moderno de Lisboa a place for a forceful and unfettered theatre.

The “independence” of the theatre companies that would exemplify this movement would be defined by two different modes: independence from meddling by the State in terms of choices of repertory, and independence from the box office. This situation would nevertheless lead to a strict “dependence” on government support for creation as this would represent the only way to safeguard any artistic freedom for the artists–with this being true in general terms even in the present day. From this movement collectives would be born that still today are central to Portugal’s theatrical life: Teatro Experimental de Cascais (dir. Carlos Avilez, 1966), a repertory theatre company, at times interventionist, at times drawing on absurdist inspiration–dazzling in its early years; A Comuna–Teatro de Pesquisa (dir. João Mota, 1972), Brookian inspired, minimalistic, ritualistic, and centred on the expressive resources of the actor; Teatro da Cornucópia (dir. Luís Miguel Cintra, 1973), an art and repertoire theatre company, known for its exacting standards and excellence; Seiva Trupe (dir. Júlio Cardoso, 1973), created in the interest of establishing more direct contact between the stage and the audience; Teatro O Bando (dir. João Brites, 1974), characterized by its intimate relationship with the plastic arts, by its use of unconventional spaces and its occasional use of monumental set machines; A Barraca (dir. Maria do Céu Guerra and Hélder Costa, 1975), a group whose initial repertory mostly selected themes from Portuguese culture and history, with music being one of the essential components of its productions; Novo Grupo–Teatro Aberto (dir. João Lourenço, 1982), with a repertory strongly linked to the German tradition and attentive to contemporary writing. To be included in this list are those theatres which have since disappeared, such as Teatro Estúdio de Lisboa (1963-1989), Grupo 4 (1966-1981), and Grupo Teatro Hoje (1975-1993)–groups which stretched the limits of theatrical revival to their greatest possible limits.

A variety of companies were founded outside of Lisbon, throughout the country, for the most part, heirs to a vibrant movement of amateur theatre that did much to enliven the 1950s, 60s, and 70s. The decentralised model, inspired by the French, served to frame the work undertaken by collectives such as the Grupo de Campolide/Companhia de Teatro de Almada (1971-1983), the Centro Cultural de Évora/CENDREV (1975-1990), GICC/Teatro das Beiras (1976-1994), Cena/Companhia Teatral de Braga (1980-1988), Teatro da Rainha (1985) Teatro Regional da Serra de Montemuro (1990), Escola da Noite (Coimbra, 1992), and ACTA – A Companhia de Teatro do Algarve (1995), among many others. Safeguarding the natural uniqueness of each group’s theatrical work, the sphere of activity of these theatre groups was one in which they disseminated a repertory of classical, national and universal import, promoted culture, and stressed local involvement and the education of the public.

With the model for organizing theatre into companies now relatively stable and less susceptible to other types of groupings, the situation in the late 1980s nevertheless began to look bleak for young actors, who despite being increasingly well trained, faced difficulties in finding professional work. Thus, various one-time freelance projects emerged, or ones with new ways of structuring the production, as in Cassefaz (1987) and Prótea–Acção Pró Teatro (1988), which combined the production, dissemination, and management aspects of theatrical projects. This new generation continued to collaborate with diverse groups and sought out other outlets for work (namely cinema and television), working without prejudice in more commercial circuits. They would quickly become the impetus for the modernization of Portuguese theatre, itself increasingly universalist and cosmopolitan.

The 1990s would provide continuity for this revival. Nonetheless, without their own venues, creators such as Lúcia Sigalho (later, in the collective Sensuround) and Mónica Calle (in the collective Casa Conveniente) would go in search of alternative spaces, their exploration playing a determining role in the provisional, intuitive, visceral, and autobiographical aspects of their first works. During this period, the work produced by collectives such as O Olho (dir. João Garcia Miguel, 1993) and Útero (dir. Miguel Moreira, 1998) also reflected the desire to create alternative forms which would begin to highlight the theatrical creations in Portugal as being some of the most original in Europe. Their impressive mark on Portuguese theatre was seen in the innovative forms with which they relate to the audience, the space, and the text, presenting performances which were invariably received as daring and radical.

The Tecedeira Que Lia Zola, by Gonçalo Amorim

April 26, 9:30 p.m., Teatro das Figuras, Faro

April 13, 9:30 pm, Teatro Aveirense, Aveiro

But also in the 1990s, at a time when the theatre company model was on the wane, groups would also form which would later go on to achieve success through their regular and coherent work. This was the case with the Teatro do Século (1983-1999), in particular the works by Inês Câmara Pestana (from 1991 onwards); the Teatro da Garagem (1989), founded on the elongated, dream-like and imagination-filled theatre of Carlos J. Pessoa who was both the primary playwright and director for the group; the Teatro Meridional (dir. Miguel Seabra and Natália Luiza, 1992) which divided its energies amongst performances which featured non-dramatic texts, performances where language did not play a central role and were essentially visual, and performances which either revisited plays from the global repertory or featured new Portuguese playwriting; and the Escola de Mulheres (dir. Fernanda Lapa, 1995), which dealt with a repertory that debated women’s issues and the place of women in theatre and in society. Later, in 1996, continuing along the vein of the Teatro da Malaposta, the Teatro dos Aloés (dir. José Peixoto) was founded, named in honor of an Athol Fugard play (A Lesson From Aloes) the group’s debut performance, which paid particular attention to a repertory of a Brechtian lineage. Also in the late 1990s and following the performance of one of the most relevant recent plays to emerge in Portuguese drama–António, Um Rapaz De Lisboa [António, A Boy From Lisbon] by Jorge Silva Melo, Artistas Unidos (AU) were created around the pivotal figure of Jorge Silva Melo (also a founder of the Cornucópia in 1973). Following a period (1995-2000) in which the company staged performances with large casts, reflecting a choral, polyphonic, electric, and monumental dimension, they then turned to plays from modern European dramaturgy in a titanic effort to highlight, disseminate, translate, and stage the most recent playwrights, the majority of whom had never been published in Portugal before. The years in which the AU performed in Lisbon (2000-2002), in an abandoned building in the heart of the Bairro Alto, at the time the Mecca for nightlife in the capital, remain to this very day as being amongst the most treasured memories of theatre in Portugal as these performances simply bubbled with vitality.

But to this we should also add the contribution of Ricardo Pais, from 1972 to his artistic direction at the São João National Theatre (TNSJ, Porto), the one whom theatre critic Paulo Eduardo Carvalho described as “one of the most singularly talented creators of Portuguese theatre of recent decades” (Carvalho, 2006: 9). Additionally, Ricardo Pais’ work at the TNSJ was in great part responsible for the revitalisation of the cultural fabric in the city of Oporto in the mid-1990s, which would pave the way for the appearance of a series of noteworthy new actors and the creation of various groups which would transform Oporto into a rather theatrically stimulating city, particularly following the investment in culture resulting from Oporto 2001–European Capital of Culture. Also involved were Assédio, As Boas Raparigas Vão para o Céu e as Más para Todo o Lado, Teatro Bruto, and Lilástico, amongst many others, and namely the work of the present director at TNSJ–Teatro Nacional de São João, the director and set designer Nuno Carinhas. It was also in Oporto where João Paulo Seara Cardoso (1956-2010) developed his work with Teatro de Marionetas do Porto, a major exponent of a rich theatre tradition in puppetry.

During the 1990s, the work of the newly established theatres and younger artists achieved a level of success which then led them to greater exposure on the national stage thanks to their overall recognition and quality. These new directors, heirs elect to the successful experimental and openly creative projects that Portuguese theatre had achieved in the 1980s and 90s, worked in non-conventional or especially adapted spaces, and were finding in the programming of structures such as Culturgest, the Belém Cultural Centre, the Municipal Theatres of São Luiz and Maria Matos, the Almada International Festival and the Alkantara Festival, the platforms that allowed them a regular and visible exposure. Of seminal importance was also the creation of the Espaço do Tempo in 2000, directed by choreographer Rui Horta at the Convento da Saudação in Montemor-o-Novo, a structure that served as an anchor for an extensive program of artists-in-residence in the areas of theatre, dance, performance, music, and visual arts intended to support promising efforts in contemporary artistic creation. These structures which aided in the creative process enabled young artists to survive and assured the continuity of their projects. Otherwise, they would find it difficult to resist to the growing precariousness of the sector, due to limited or occasional access to State-awarded financing and to a lack of a permanent performing space.

Rui Horta talks about the importance of losing oneself. To make the loss a method, especially when the experience of life tends to become a weight that leads us not to risk. The loss, then, as a method.

What also played a determining role in the work carried out by this new generation of theatrical creators was, for the most part, their regular presence on the international circuit. This participation proved to benefit them via shared experiences within a transnational movement that put artistic codes and languages into greater harmony with the most recent trends in the performing arts. These young theatre collectives and creators allied their inventiveness and creativity with ongoing research into the specificities of theatrical language, often working on the boundary between the arts, crisscrossing different artistic modeling, and navigating in and amongst theatre, narration, new dance, video, and artistic installations.

Without eroding the singularity of the artistic work achieved by any of these theatre artists, companies, or structures for a theatrical production in question, we can trace some thematic axes, many shared concerns, and various modes for approaching great formal and aesthetic proximity. There is–and this is one of the most singular aspects of theatre today in Portugal–a constant circulation of artists working in a wide variety of projects and assuming different degrees of responsibility in each undertaking, which highlights the particularly high level of closeness, which denounces a singular generational complicity.

This article was originally published as “Introduction” to the edited collection entitled Contemporary Portuguese Theatre: Experimentalism, Politics And Utopia [Working Title] (edited by Rui Pina Coelho). Lisboa: Teatro Nacional D. Maria II / Bicho do Mato, 2017.

Rui Horta talks about the importance of losing oneself. To make loss a method, especially when the experience of life tends to become a weight that leads us not to risk. The loss, then, as a method.

We are grateful to the publisher for granting us permission to re-publish this article.

Bibliographical references:

GAYO, Afonso (1923), Evolução do teatro português contemporâneo (conferência realizada, em 25 de Março de 1923, na Sala da Sociedade Nacional das Belas Artes e promovida pela Associação de Classe dos Trabalhadores de Teatro), Lisboa: Associação de Classe dos Trabalhadores de Teatro.

REBELLO, Luiz Francisco (1996), Teatro-Estúdio do Salitre – 50 anos, 9 peças em 1 acto. Prefácio de Luiz Francisco Rebello, Lisboa: Sociedade Portuguesa de Autores/ Publicações Dom Quixote, pp. 11-27.

CARVALHO, Paulo Eduardo (2006), Ricardo Pais: Actos e Variedades. Porto: Campo das Letras.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Rui Pina Coelho.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.