Of all the non-human animals that human animals love, the primate is the most embarrassing. (The syntax of the previous sentence shows how incestuous this relationship is: what are we if not animals, what animals if not primates?) They’re the best at simulating our actions, activities, and expressions, so they’re the easiest to project our emotions onto. Sometimes we coax them towards language, like Koko, the late sign language savant, sometimes towards love, like Michael Jackson’s euphemism Bubbles. These attachments can form quickly too, in as little time as it takes for a monkey to pick up the pair of sunglasses or disposable camera in their enclosure at the zoo. The embarrassment comes in because resemblance is always a mutual relation. We can’t realize that they are like us, without acknowledging that we are just like them.

Chimpanzee, at HERE Arts Center, is a puppet show written and directed by Nick Lehane that explores these tensions, and it’s an extraordinary and heartbreaking piece. It’s the story of a single chimp looking back over a life spent in different kinds of human environments. Memories of a happy but strange and artificial domesticity punctuate her bleak and isolated existence in some kind of institution.

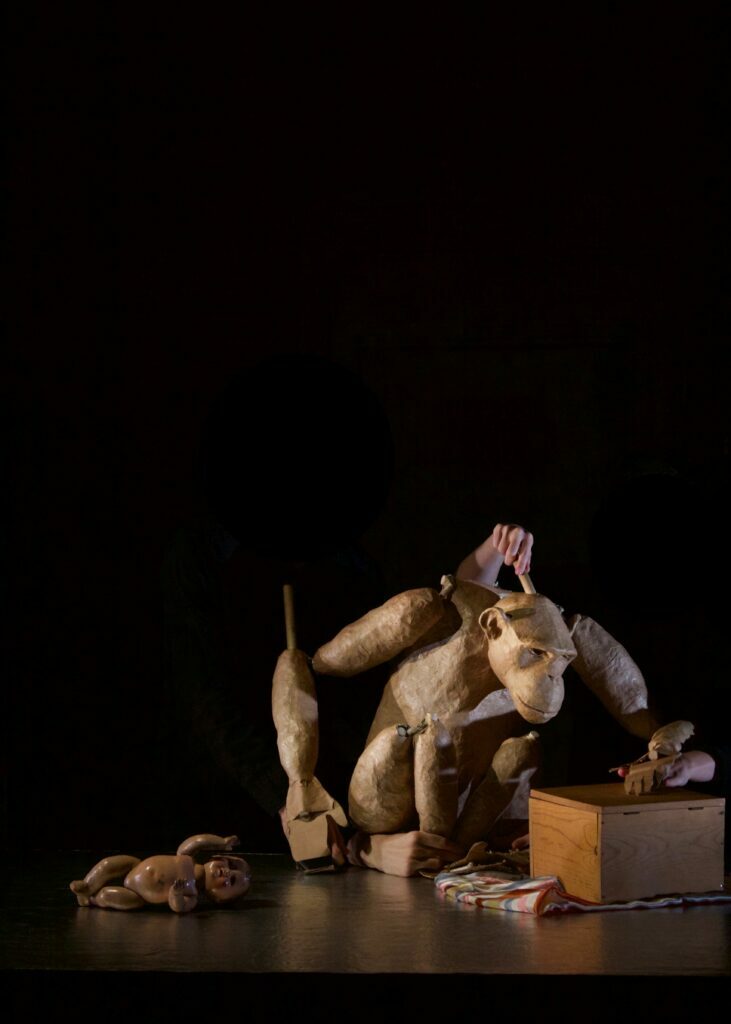

Photo by Richard Termine.

Where is she exactly, and where was that happy past? There’s no dialogue, no set save for a raised platform, and no other characters to provide sign-posts. And yet there’s an exquisite specificity to the emotions she expresses. (There’s no gender specificity though. I’m using “she” arbitrarily.) She bends her knees against her chest, arms wrapped around herself, and rocks slightly back and forth, displaying her fear and loneliness, looking like someone wrongly accused in solitary confinement. She runs freely, climbs trees, swings from branches. She breathes. The audience didn’t need any dialogue to know what she was feeling.

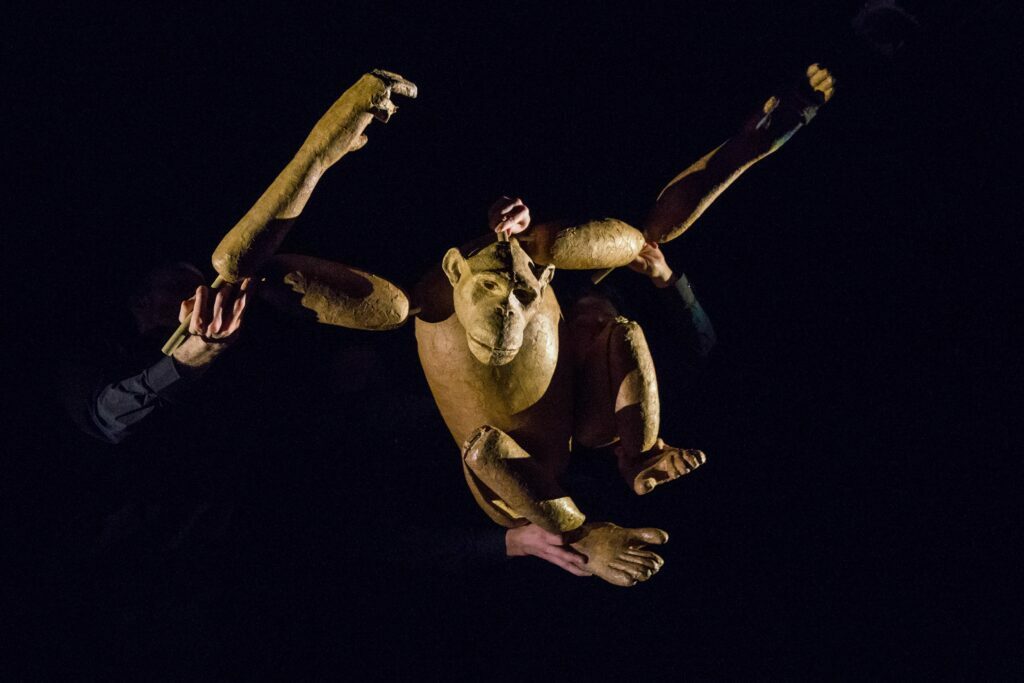

Photo by Richard Termine.

All the particularity of the chimp’s experience comes from the technical virtuosity of the puppetry. The life-sized puppet was worked by three puppeteers: Emma Wiseman on her head and left limbs, Rowan Magee on her torso and left limbs, and Andy Manjuck adding the extra touches that make her movements so nuanced, as well as providing props for her to interact with, like a baby doll, a teacup, and kettle, a box of scarves, a rubber duckie. The construction of the puppet allows for dynamic motion: her arms, legs, and head are jointed, and the palm of her left hand has a band in which Magee occasionally inserted his hand, giving her opposable fingers.

So much of the puppet’s body is mobile and malleable, but apart from a mouth that opens, there’s no movement in her face. That makes her range of expressions all the more impressive, but it also forces us to confront the question of whether she is, in fact, a blank slate. How embarrassing!

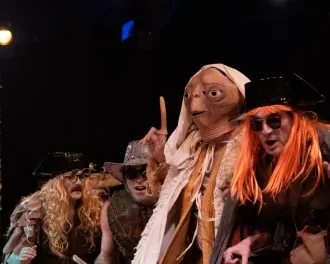

Photo by Marika Kent.

The puppeteers are visible onstage throughout the show, and while they aren’t really characters, they occasionally fill the role of the chimp’s keepers/owners/captors. Many of the objects she uses appear as if out of nowhere, thanks to the pitch-darkness of the surrounding stage. But sometimes the puppeteers interact with her: feeding her, running her a bath. Sometimes she looks to them for comfort, sometimes she rages against them.

Puppetry itself becomes a meaningful metaphor in this show. After all, what do puppeteers do to a puppet? They give it life, but they also control it and manipulate it. It’s the dramatic equivalent of a master-slave relationship. This show, produced by the Jim Henson Foundation, was inspired by the now illegal practice raising chimpanzees as human children in private homes and then dumping them in research labs. It’s a story that could be told through any number of means–documentary footage, animation, a feature film (with the cooperation of the American Humane Society). But only live theater allows us to understand this phenomenon so intimately, and only puppetry reifies the tendentious relationship the show explores.

In fact, you don’t need to know about the factual basis of this show to be moved by it. Chimpanzee isn’t a work of protest art; it’s a depiction of a relationship, a quest for love, a miscommunication. Art about animals is never about the animals, is it? And this kind of simian simulation, well, it’s the most obviously autobiographical.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Abigail Weil.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.