Attending a performance of a classic work is always a humbling experience. Getting in touch with words and meanings so uniquely conceived and put together centuries ago brings you back to the foundations of the art of theater and the roots of the humankind. How is it possible that plays like these continue to be ever relevant and resonating with audiences of every era?

That very question brings on the thought that such texts, if you approach them with respect and humility, possess the power to create a theatrical experience without the need of external means. If directors and actors dig really deeply and analyze what the playwright was aiming for, then the words and their sense shine and reach the audience. This is a time-consuming process that emanates from within and later on is depicted on the body and voice of the actor and on the production choices.

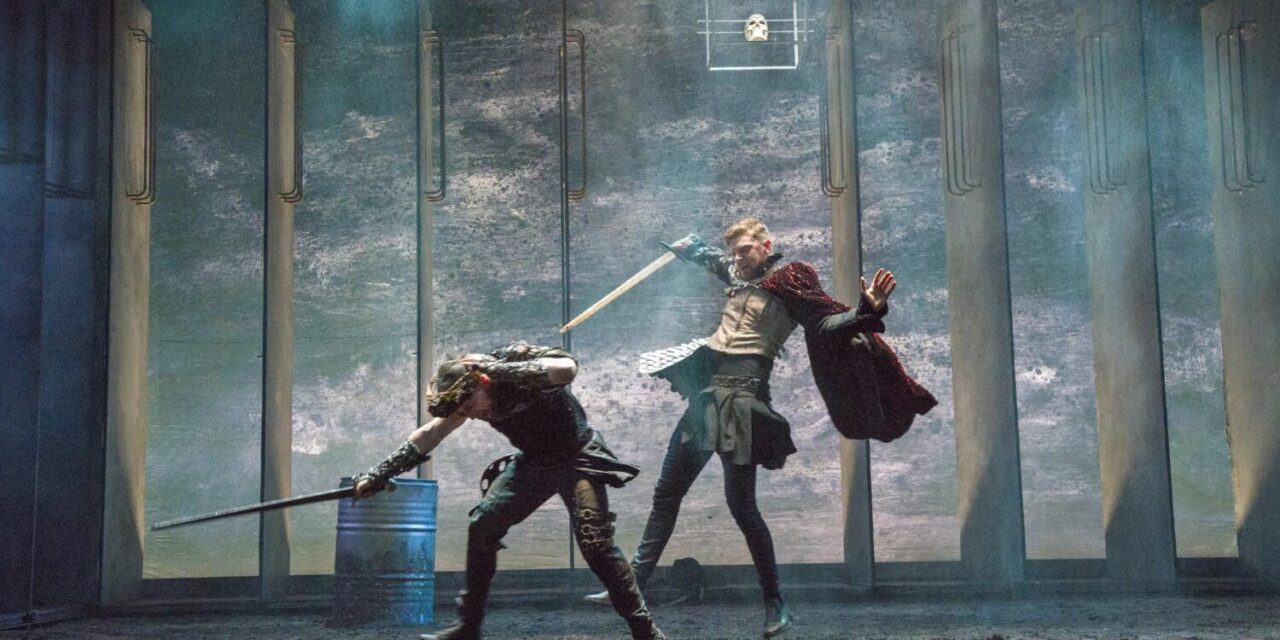

Aaron Monaghan as Richard III. Photo Credit: Richard Termine.

Back in 1979, when Sir Ian McKellen gave a Masterclass on Shakespeare, he said: “If you look after the sense, the sounds take care of themselves. I saw Maurizio Pollini play a late Beethoven Sonata recently, and I had a strange feeling. I did not know whether he was putting the music into the piano or whether he was taking it out of the piano. Acting at its best is in Shakespeare, I think, of that nature – that the actor is the playwright and the character simultaneously. This can only be achieved by the actor having total awareness of all the complexities of Shakespeare … it is not enough to put the quality of despair into the voice and just follow the rhythms. You’ve got to do other things, you have to think and have analyzed in rehearsal totally so that your imagination is being fed by the concrete metaphors, concrete images that can then feed into the body, gesture, into timbre of voice, into eyelids, into every part of the actor’s make up.”

In this specific Shakespearean production of Richard III by the Druid Ensemble, the above was not applied. The production was designed based on external elements that were not organically connected to the text and intention of the playwright. A series of questions filled my mind. What was the motivation behind the choice of sets and costumes? In my opinion, the only thing that really worked well set wise was the ever-present void on stage, the grave downstage in which all bodies were thrown in – a constant reminder of death and of Richard’s deeds. As a side note, I must say that maybe the production would look different if it was presented in a black box theater. I missed the focused feeling a theater like that offers, as at Gerald W. Lynch Theater, there was no total black out in the hall, and I found that this was taking away from the stage.

Aaron Monaghan as Richard III. Photo Credit: Richard Termine

Why was the inflection of the actors so flat? With the exception of Aaron Monaghan, who played Richard, all of the actors did not sound like they had “digested” the text, they were just saying the words, and at times, even the diction was problematic. Monaghan had an extremely clear diction, and his voice carried well in space throughout the performance; however, his inflection, as well his body movements and gestures, were informed externally rather than from a deep understanding of the role. To me, his body was almost a caricature and his portrayal of the character lacked the bitterness and the darkness of a person like Richard.

I left the theater that evening in awe of Shakespeare’s work, but without it being in that transcendent state you expect to reach when you have the opportunity to attend productions of classic works.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Antigoni Gaitana.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.