Juan Mayorga has been keeping busy. He was recently elected to the Royal Spanish Academy—the foremost national body for the preservation and promotion of the Spanish language—and he has three stagings traveling around Spain. One of his most popular works, El chico de la ultima fila (English title The Boy At The Back)—with over 25 professional productions across the globe to date in addition to a radio version realised by the BBC in 2014 and a film adaptation, Dans la maison (English title In The House) made by François Ozon in 2012—is now touring Catalonia. Following a run at Barcelona’s Sala Beckett and directed by Andrés Lima, it boasts Sergi López in the role of the high school teacher increasingly obsessed with the narratives of a sharp but unpredictable student in his class. El mago (English title The Magician) is also touring through Spain following its opening at Madrid’s Centro Dramático Nacional in late November. Intensamente azules (English title Intensely Blue), opened in June 2018 and remains on tour through 2019 with a month-long run at Madrid’s Teatro de la Abadía from January 10 to February 10. Developed from a short story with illustrations by Daniel Montero Galán first published by La uña rota books in 2017, Mayorga crafts a one-man show for César Sarachu—the pair had previously worked together on Rejkavik (2015) where the Basque actor again took on a plethora of different roles. Sarachu is perhaps best known for his role as Joseph, the Schulz alter-ego in Complicité’s Street Of Crocodiles (1992) but the Lecoq-trained actor has also worked in France with Peter Brook, Sweden with Susanne Osten, and Spain on Luis Guridi’s Camera Café.

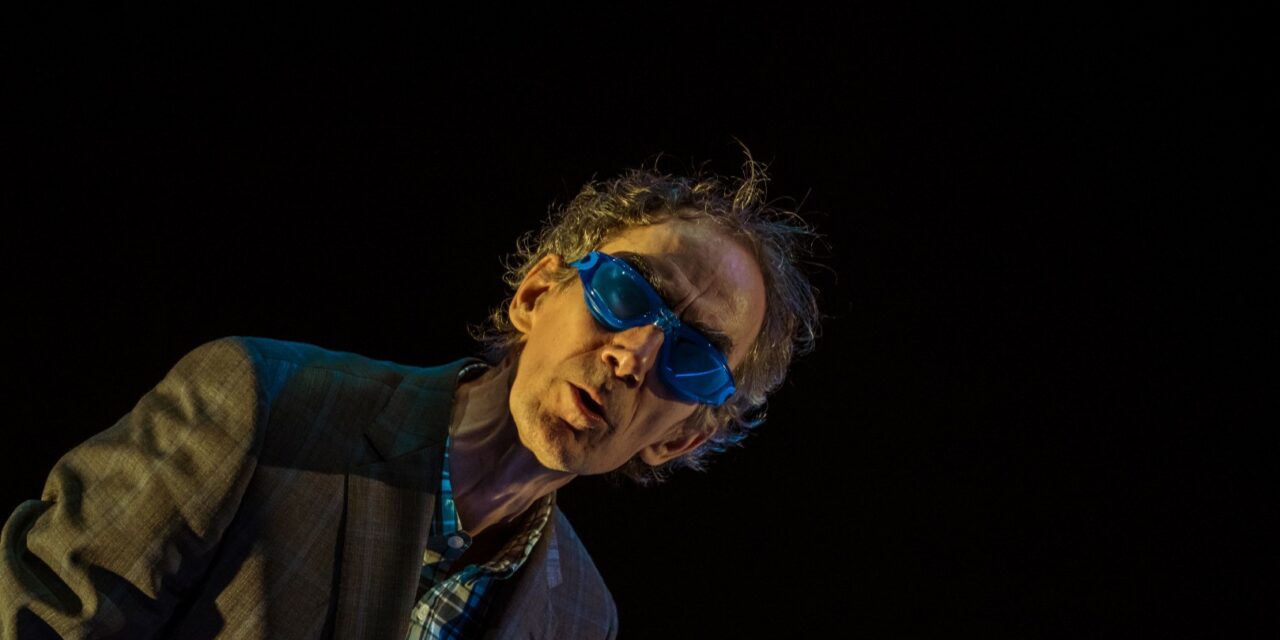

For Intensely Blue, Sarachu plays a middle-aged father of three who wakes up one morning to find that his glasses have broken; when he takes to wearing his prescription blue-lensed swimming goggles instead, he finds the world looks very different. The premise of the play is based on an incident suffered by Mayorga while on holiday in Andalusia some years back. He had no alternative but to wear his swimming goggles for a week while his glasses were being repaired. He discovered that on wearing the goggles around the house and to the supermarket others viewed him rather differently—predominantly as a threat or as someone in need of help. He sat down to write about the experience and Intensely Blue is the result.

Alejandro Andújar creates a rectangular set that shifts colors depending on the mood of the scene. A fluorescent line marks out the parameters of the space where the tall, angular Sarachu creates the world of the play. The line mutates across different colors capturing the production’s shift of moods. When the goggles go on it is as if he is walking in water, finding his way through new, unfamiliar terrain. The world becomes a new space of discovery and wonder as the unnamed protagonist looks at things, literally, through different eyes. He reads Don Quixote and “understands things that I had never previously comprehended.” Turning to Schopenhauer’s The World As Will and Representation he makes sense of the mammoth work for the first time: the world as representation, the object as perception itself, object and subject unable to be separated.

And this is, in essence, the focus of Mayorga’s piece with Jordi Francés’s busy soundscape and Juan Gómez Cornejo’s shifting light—moving from bright blue to faded yellow—used to conjure a visual accompaniment to the experiences narrated by Sarachu. The whirring sound of a projector and flickering light accompanies his narrative of having seen Buñuel’s 1929 film Un chien andalou seven times in a row—black and white reframed through brightest blue. He creates a bed from a lime green double pillow and plays both himself and his wife conversing in bed. The Royal Palace is evoked by the sound of the Spanish National anthem. The underground Number i bar is induced through the melancholy sound of an accordion. The local pool is conjured through a swimming cap—particularly entertaining is his fight with a fellow swimmer who steals his goggles, leading Sarachu to conclude, ironically, that he had best not take his goggles to the pool any longer. His youngest daughter—who doesn’t want him to go watch her play with his goggles—is conjured initially through a basketball, that he bounces around to show her bubbly energy; he sways petulantly as he articulates her insistence that he only comes to watch her play if he sits well away from the other parents. The noise of crowds around the court accompanies Sarachu’s ebullient bouncing of the ball in search of the net. His rebellious middle daughter is shown through a can of (bright blue) paint that he sprays in front of the audience—she doesn’t want him to go to her wedding if he plans on wearing his goggles. “I didn’t know you had a boyfriend,” he replies. “I don’t,” she retorts, “It’s just a warning.” His energetic son embodied through a camera—a great metaphor for a generation who have grown up mediating reality through their smartphones—lays down some ground rules. “The swimming goggles are not to be used at weddings, baptisms, and funerals.” Sarachu appropriates each of the objects to initiate the shift of role. They remain on stage as embodiments of the different family members.

Objects acquire a new identity before his eyes. He spends hours gazing at Velázquez’s Las meninas (The Ladies In Waiting) at the Prado museum while a security guard watches him obsessively. He paints blue goggles onto all his photos, embracing the new gaze with a keenness that borders on fixation. He fights with a fellow swimmer who steals his glasses, his body tussling brusquely with the imaginary assailant. He takes to observing people and notices things never seen previously—as with an elderly nun feigning a limp. He leans ominously forward, follows a woman with red swimming goggles through the deserted streets of Madrid with the aplomb of Peter Sellers Inspector Clouseau.

Sarachu is an extraordinarily precise actor: lean and balletic, he moves like a pair of scissors, his long legs cutting through the stage with a sense of urgency and resolve. The classic imagery of Don Quixote appears evoked in his poses and demeanor—a man slightly out of tune with the world around him. Arriving home late at night following a night drinking with fellow revelers, all sporting different colored swimming goggles and all Schopenhauer-obsessed, his long fingers serve as keys that let him into the apartment. He creeps delicately on tiptoes around the marital bed, swaying uncertainly before his sleeping wife. His large hands open out like butterflies as he narrates his experiences in the downtown bar. At the pool, he removes his clothes as if they were tissue paper. He takes on a range of characters—from the prim and proper civil servant staring down at her papers as she considers whether she will issue the family’s passports to the King of Spain waving to the crowds—shifting in and out of a role with the most minimal of moves. Lean and dexterous, he suggests pathos, vulnerability or agitation through the shift of an arm, the arching of an eyebrow.

Intensely Blue is ultimately a work about the possibility of seeing the world differently—something too few of our political leaders currently seem able to do. References to the constitutional crisis over Catalonia suggest a world where listening needs to be prioritised anew. The swimming goggles are open up new avenues of conversation leading the King to incorporate Schopenhauer into his Christmas address and hand the visiting President of the United States a copy of The World As Will And Representation. Disney are even riding the wave with plans to make a movie version of Schopenhauer’s work complete with musical numbers and a happy ending. These blue goggles have opened up a range of different possibilities: new friends at the Number i club; a new relationship to the monarchy; new readings of the canon; and a way “accepting everything that comes my way.” When he decides to wear the goggles for an official dinner with the Icelandic President at the Spanish Royal Palace, he observes that they are airbrushed out of official photographs of the event. He doesn’t take it personally: the Icelandic President has been retouched also and is now wearing a formal evening suit.

There is gloriously playful quality to Mayorga’s production. A plain box stage left serves as a magic toybox filled with objects that Sarachu uses to create the different scenarios: the weighty volume of Schopenhauer, the wedding photo he has now retouched; the items that represent his three children. For seventy minutes Sarachu dances across the stage creating the world of Mayorga’s protagonist, his family and the different individuals he comes into contact with—from the intense Number i bar regulars to the monarch’s security guard. The sensation, much like Philippe Quesne’s L’effete de Serge, is one where the audience see objects given a new agency and identity. Intensely Blue is a deliciously amusing play but it is one that is not afraid to scratch at some of the discontents currently eroding contemporary society. And in Sarachu Mayorga has located an actor capable of personifying wildly different elements of a community engaging with one man’s quirky new-found view of the world.

Intensely Blue, presented by La Loca de la Casa theatre company, remains on tour during 2019.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Maria Delgado.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.