Francisco Nieva (1924-2016) ranks amongst the most respected Spanish playwrights of the second half of the twentieth century. The seat of the National Dramatic Centre in the hip Madrid neighborhood of Lavapiés has two auditoriums: the larger named in honor of Ramón María del Valle Inclán (1866-1936) and the smaller after Nieva. Inspired by the grotesque humor of Valle-Inclán’s dramatic output, Nieva’s plays are irreverent (he experienced several problems with censorship during the Franco dictatorship), and technically demanding. Requiring large casts and elaborate uses of space and costume design, the plays are studied more than they are staged. Written shortly before Franco’s death in 1974, Coronada and the Bull did not premiere until 1982, with a lavish state-funded production directed and designed by Nieva himself. The play promptly disappeared from the professional stage for four decades. Coronada’s return in 2023 to a smaller space in the Matadero, a former abattoir turned cultural center in Madrid, bore testament to the quality of Nieva’s play as well as the talent and tenacity of director Rakel Camacho and her company.

Conversely, however, it also underlined the text’s status as a difficult contemporary classic.

As a director and dramaturg, the forty-four year-old Camacho has had a varied career, staging works by canonical authors such as Federico García Lorca or Yasmina Reza as well as a theatrical adaptation of a Roberto Bolaño novel. A desire to forge a more unconventional trajectory is evident in her participation in a project bringing together professionals from the theatre and the circus alongside her willingness to embrace a rich Spanish literary dramatic tradition that often struggles to find a convincing stage register through productions of, say, Valle Inclán. She also has prior history with Nieva, having staged another of his plays, The Chariot of Red Hot Lead, as a graduation project at Madrid’s Royal School of Dramatic Arts.

Nieva and Camacho were both born in La Mancha, the rural plains of Castile best known internationally as home to Miguel de Cervantes’s Don Quixote. Within Spain, it is an area often disregarded as the natural habitat for all that is most archaic and barbaric in the country’s soul. Coronada and the Bull continues a venerable tradition in Spanish theatre for using rural festivities as a gateway into broader reflections on the customs and psychology of its people. Garrulous bully Zebedeo is the local mayor, in perpetuity, of the fictional village of Farolillo de San Blas. His biggest delight is presiding over the annual local festivities.

Confronted by Coronada, his unmarried sister, over the village’s celebrations for the local patron saint, he responds by locking her up indoors. The festivities do not in any case go to plan. The non-human participant in an amateur bullfight refuses to emerge into the open air, defying the expectations of both the on- and off-stage audiences. Unwittingly, the wild beast instead wanders into Coronada’s house. She provides sanctuary from her bullying brother – the unlikely tandem of bull and woman are joined by townsfolk, including a bearded male nun, united in their suffering at the hands of and resistance to Zebedeo’s tyrannical rule.

Following a dramatic tradition crafted by Valle-Inclán, Nieva’s depiction of the village is ambivalent. On the one hand, he is critical of Spain’s antiquated conservative forces. Conversely, however, he remains captivated by the irrational and primitive world of traditional costumes and rituals. Lacking the budget of the original 1982 production and its lavish mise-en-scène, Camacho relies instead on imagination to resolve the text’s difficult demands, using a ludic approach to capitalize on the energy and teamwork of her ensemble.

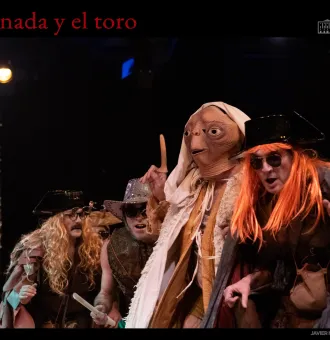

As spectators took their seats around a centre-stage, in their sight lines were legs of ham of the kind seen in both traditional and tourist-trap Spanish bars. The production began with the large cast (11 actors) storming the stage, their costumes and dancing a mixture of kitsch references from past and present: Zebedeo rehearsed a Robocop dance; the priest shook his hips Shakira style; and even E.T made an appearance. With characters consuming cocaine, Camacho’s contemporary take was particularly good at emphasizing the mix of rigidity and complete lack of control that so often characterizes such small-town celebrations.

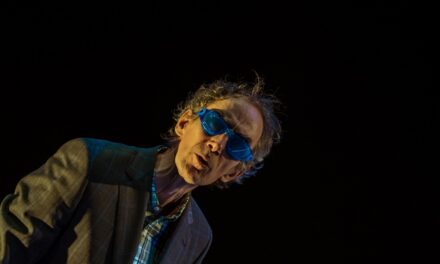

During the first few scenes, the audience engaged, clapping along and laughing at the parody of festive songs and exuberance. Not everyone, however, stayed on for the ride. The school groups present behaved more respectfully than some of the adults on their mobiles, one even clapping sarcastically at the end of a scene some two hours into the production in the hope the play itself had finished. The elaborate baroque expression and wordplay in turns of phrases no longer in circulation (relating, for example, to tauromachy) render Nieva’s plays difficult to follow for the uninitiated. Also potentially off-putting for audiences more accustomed to conventional realist fare was the production’s aesthetics. Camacho used tricks from her previous work in the circus, whilst being au-faux with performance techniques characteristic of recent post-dramatic theatre. The climax of the First Part involved the imprisoned Coronada defiantly stripping and masturbating. Whilst this action was understated and implicit in the 1982 production, in 2023 it was brought to the fore with a voyeuristic appropriation of the aesthetics of Angélica Liddell, Spain’s leading practitioner of performance art in traditional theatrical spaces. Another scene, this time created from scratch by Camacho, in which Coronada and her followers share some churros with chocolate, tipping it over each other’s bodies, recalled the food games associated with the work of Rodrigo García, a key reference point for the contemporary avant-garde in and beyond Spain.

One of the production’s highlights was the rereading of the male nun, rendered in a different universe to the grotesque creation of Nieva’s production to become a hyper-sensual drag queen (whose abilities on raised heels had to be seen to be believed). A celebratory approach to queer hybridity (the low with the high, the old with the new) was intimated through the substitution of a dark song and dance that Zebedeo, shotgun in hand, forces the townsfolk to sing and dance in an almost Voodoo-like conjuring act to coach the bull into the open air with another that invites them “to embrace difference”. Many spectators had, unfortunately, switched off by this stage. Theatre in Spain still receives relatively generous subsidies. The inability of much of the audience, reared on literary-text-based theatre, to appreciate many of this production’s qualities lends itself to two opposing conclusions. If the Spanish taxpayer is obliged to contribute to the theatre in publicly-run spaces, perhaps the least they can ask for in return is the right not to be bored? The counter-argument is that the niche appeal of such work requires protection by non-commercial theatrical spaces because, otherwise, this remarkably rich vein of Spanish theatre is seemingly doomed to disappear.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by María Bastianes and Duncan Wheeler.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.