I caught up with The Thanksgiving Play a few days after Thanksgiving. I was in the mood to laugh and figured I might learn something. This work by Larissa FastHorse is (according to The Interval) the first full-length play by a Native American to be fully produced in a major New York theater. That seemed pretty important.

Reviewers had called it a sharp satire. I was (am) woefully ignorant about Native American cultural politics and know next to nothing about NA views on Thanksgiving (you can’t read everything). The air, as always in November, was full of anodyne pabulum about turkeys and pilgrims and magically abundant corn—all those childish tokens of social concord we use to evoke a harmonious Eden our country never really had. I put on my shoes to go get happy and woke.

How strange, then, to find that this play offered little corrective to any of that. It turned out to be an extended gag about the cluelessness of politically correct white people that, disturbingly and incongruously, recapitulated the historical erasure of Native Americans. Ha, ha, indeed.

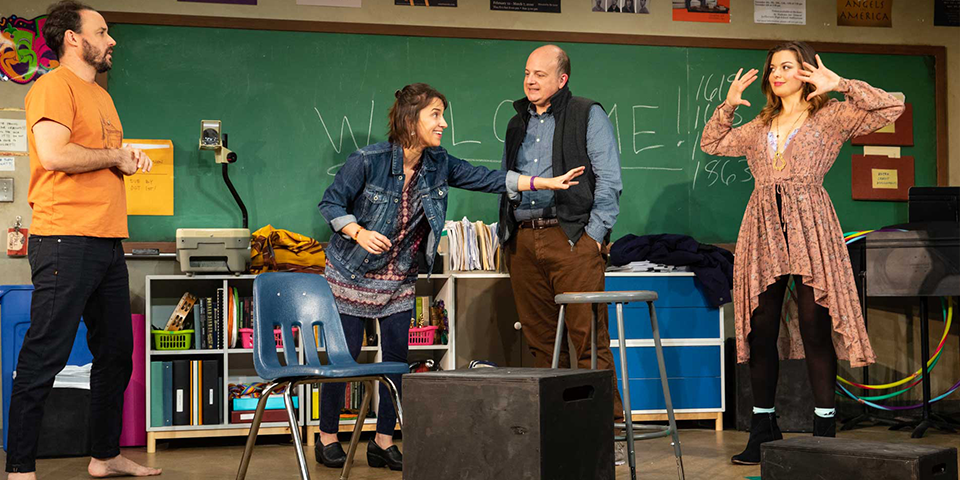

The Thanksgiving Play is constructed around a single situational joke, hammered home with a variety of comic nails over 90 minutes: a group of well-meaning white folks meet to devise a school Thanksgiving play that is sensitive to privilege and genocide…but it has no Native Americans in it.

The plucky and hip director Logan (Jennifer Bareilles, perfectly insufferable) thought she had an NA actress. Her “Native American Heritage Month Awareness Through Art Grant” was supposed to be used to hire one. The self-absorbed ditz who shows up, though—Alicia (a terrific Margo Seibert)—is no such thing. Her head shot taken with braids and a turquoise necklace fooled Logan (“Every actress in LA has different types of shots. My agent told me to.”) So much for due diligence.

The rest of the play, adroitly directed by Moritz von Stuelpnagel, rides this comic wavelet, such as it is, with a succession of hapless attempts to rescue the playmaking project while skewering the participants for their various foibles. Logan spouts female empowerment and trust in “inner beauty,” then laps up Alicia’s advice about makeup and hair-flipping. Jaxton (Greg Keller), a street performer who is Logan’s boyfriend, is so ridiculously open-minded he sees both sides of her direct insults (“You’re a terrible actor!” “I know that her lashing out is not about her and me but actually her double X’s fighting back against centuries of patriarchal oppression.”)

Caden (Jeffrey Bean, duly wry), an elementary school teacher who not-so-secretly wants to be a playwright, has been assigned to the project as a historical consultant. He is the sanest of the group and has come with a thick sheaf of new-written pages, hoping to try his scenes out.

Caden is the reason the play feels vaguely promising even after its satire grows monotonous after 20 minutes. His research seems like a vehicle to finally teach us something within FastHorse’s farcical frame—something we didn’t know, say, about Native American history, customs, thought, or even the story of Thanksgiving. That hope too is crushed, though, because everyone else treats his scene suggestions as diffuse or inappropriate and quickly dismisses them.

In the end Logan’s brain-wave—her brilliant means of avoiding “red-face” (that no-go option of Caucasian actors portraying Native Americans)—is to ditch writing and acting entirely and simply make a play of “nothingness”: “We’ve been trying too hard. The empty space is completely, finally equal. That is our Thanksgiving play.”

FastHorse has said her motivation for writing The Thanksgiving Play was her repeated rejection by American theaters due to casting excuses. I quote her at length so as not to edit her.

I’m gonna get myself fired from American theater for telling this story. The reality is that the number one reason that I’m given for my plays not getting produced is casting. My past plays have all had at least one Indigenous character in them, and theaters believe they can’t find actors for the parts. (We can debate about this for a long time, but this is what I am told, often after they have already passed.) I know that American audiences are hungry to learn more about Native American issues through art because otherwise they don’t learn about them in this country. So, I set a challenge for myself to write a play that deals with Native American issues and in a way that removes the excuse of casting difficulty from the equation. I wish this was not a necessary step to get Indigenous stories into the cannon [sic], but this is where we are. However, I do like this play very much, and it is getting produced. (interview in DC Metro, Oct. 10, 2016)

These remarks raise some pointed questions.

First, did the stratagem succeed? Will this major New York production open up production opportunities for her other works? Or for plays by other Indigenous dramatists? We’ll see.

Second, was the ploy worth it? Apart from the tacit erasure of Native Americans, FastHorse has risked the appearance of vindictiveness, of having introduced herself to the New York theater world by basically mocking its prime demographic.

Third, what has Playwrights Horizons’s position been on the issues FastHorse raises? Did Tim Sanford choose this play over her others because he thought it was her best? And did he also raise “excuse[s] of casting difficulty?”

Playwrights Horizons’s web page for The Thanksgiving Play contains, among a slew of other great supporting materials, an article by Emma Miller about “the large community of Native artists making work here in New York City.” How did the theater’s awareness of this pool of artists affect its choices here? And did anybody consider the obvious choice of casting all the roles with NAs—surely the best rejoinder possible to the doubters out there?

I have no answers to any of these questions. Yet they are irretrievably out there now, and we should all hope the conversation continues.

The Thanksgiving Play

By Larissa FastHorse

Directed by Moritz von Stuelpnagel

Playwrights Horizons

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Jonathan Kalb.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.