The political mantra “Nothing about us without us” is hard to object to immediately–it makes sense, it relies on self-awareness and cultural sensitivity, it even rhymes. Allies and social justice activists do well to keep this in mind, especially when advocating for groups of which we’re not members. It’s also healthy and important for policy-makers, for example, and doctors, to be aware of their own privilege and outsider status vis-à-vis the group they’re trying to help. But this kind of thinking is also fraught. When it comes to art, a dictum that can be productive quickly becomes paralyzing.

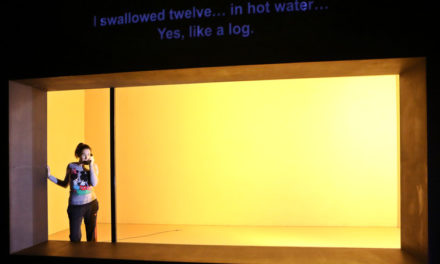

This is one of the problems that Larissa FastHorse tackles in The Thanksgiving Play at Playwrights Horizon. FastHorse, a member of the Lakota nation, has achieved something rare and wonderful with this play: out of the darkest, saddest, most infuriating material, she’s crafted a hilarious comedy. The play reifies the literal and figurative erasure of Native Americans from the American landscape and consciousness as two “woke” white theater artists, Logan (Jennifer Bareilles) and her boyfriend Jaxton (Greg Keller), try to create a Thanksgiving play that pleases the school board, satisfies the requirements of their grant funding, and eases their own political consciences. They have a perfectly admirable plan to thwart traditional power structures: this will be a devised theater experience, with input from Caden (Jeffrey Bean) a local history teacher/amateur playwright to keep it historically accurate, and in the lead role, a real live Native American actress.

Genius at work – the play satirizes devised theater and its proponents.

But they’re out-thwarted when their good intentions can’t compensate for the reality they’re up against. Devised theater proves too unruly an experiment and that Native American actress? Margo Seibert in a pitch-perfect performance plays Alicia, “French, English, and a little Spanish we think!” In other words, she’s white. At her agent’s suggestion, she has been circulating multiple headshots suggestive of the different ethnicities she can play. Logan took her Native American-looking shot, whatever that means, at face-value, and as Alicia informs her, “That’s on you.”

For Logan and Jaxton, the absence of an authentic Native American voice in the play becomes a crisis. But of course, that’s the Thanksgiving play within The Thanksgiving Play. The entire work is the expression of a Native American voice; it’s a world of FastHorse’s making, and her jokes that keep the audience in stitches. Towards the end of the play, Jaxton gives the lie to his own understanding of racial privilege, arguing that soon white people will be a minority, and wondering whether he has a right to speak for them. One of the most effective ironies of the play is FastHorse’s readiness to “speak for” these white characters. She’s rearranging what it means to be othered, and showing that “Nothing about us without us” would leave the art world dangerously under-populated.

By locating the conflict in the efforts of two white artist-activists, she doubles down on the problem of erasure, affecting authorial self-effacement and shifting the responsibility to her characters. At the same time, it’s a sympathetic depiction of people struggling with the crucial issue of representation. Logan and Jaxton, and by extension everybody like them (which, admittedly, includes the author of this review), are skewered, but lovingly.

As I watched the play, I thought that a bit more humanity could be squeezed out of those characters if Bareilles and Keller dialed back their performances, just from eleven down to nine. Logan and Jaxton are played as caricatures, which robs the characters of the complexity that FastHorse’s script endows them with. But on reflection, I wonder if this isn’t a response to hundreds of years of Native American caricaturing? I was born in Cleveland, Ohio, a city whose baseball team, the Indians, is represented by the logo Chief Wahoo, a big-nosed, big-teethed, befeathered cartoon created in 1932 and basically unchanged to this day. Chief Wahoo was the first “Indian” I ever saw; Tiger Lily, wooden statues outside cigar stores, the Land o’ Lakes princess, and Apache by Sugarhill Gang rounded out my concept. After all that, I think I can handle ninety minutes of caricatured whiteness. Not in the interest of settling scores, but to understand what FastHorse is up to: if Jaxton and Logan come across as unidimensional, it serves the scaffolding of dramatic conceits. And when their lofty ideals give way to more banal concerns (professional ambition, physical attractiveness), we see how performative their politics were all along.

I must say, however, that Jeffrey Bean plays Caden with such earnestness and genuine enthusiasm, you end up rooting for him and his historically-accurate script. And although Alicia, a hot, dumb actress, is a somewhat clichéd character, Seibert infuses her with real warmth. There is a conflict between her and Logan, not only in their competition for Jaxton’s attention but also in the fulfillment of the role of modern womanhood. In one of the more subtle examples of the blinding drive of political idealism, the feminist Logan refers to Alicia as an actor, but Alicia calls herself an actress. One way to read Caden and Alicia, single-minded in their respective purposes and happy because they are unfettered by political anxieties is as a contemporary play on the “noble savage” trope. But they also add levity, balancing out the activisty sophistry of the other two. For me, one of the funniest moments of the play comes during their initial blocking of The First Thanksgiving Dinner, when Alicia mimes a pepper-mill.

How to treat history in art is only one of FastHorse’s concerns; how to teach it in school is another. After all, the play-within-the-play is being devised for a public middle school (although it’s never explained why there are no kids in this school play). The play is punctuated by a series of children’s songs arranged in order of grade-level and would-be enlightenment. The show opens with a Thanksgiving-themed parody of The Twelve Days Of Christmas (“Fiiiive pairs of moccasins!”) and escalates to a rap about police violence at a National Day of Mourning demonstration in 1997. The songs function as mini-Thanksgiving pageants, as well as a reminder that what is deemed appropriate for the classroom is always subject to recall. And can we talk about that moment in the 90s when mostly white teachers embraced rap as a teaching tool?

As a satire of white social justice crusading, the play moves into the same neighborhood as Get Out. But it also called to my mind another work, the short-lived but brilliant Comedy Central show Strangers With Candy. The episode Trail Of Tears begins with an exaggerated casting of a Thanksgiving play, with all the white students eager to play pilgrims and the school’s one ethnically ambiguous brown student unhappily made to take the role of the savage Indian. Later the heroine Jerri Blank (Amy Sedaris), having learned that she was adopted from a Native American family, enrolls in the Bob Whitely Cultural Immersion Camp For Adopted Indians. Whitely, a well-intentioned white guy played by Will Ferrell, has made it his mission to teach his campers about the glories of their heritage; camp activities include archery, sending smoke signals, dealing blackjack and passing around a peace pipe (bong.) When Jerri returns to her high school, she proudly brings her own Native American heritage to bear on the role of the Indian in the Thanksgiving play, improvising a speech in which she deeds the continental United States plus Alaska and Hawaii to the white man.

Strangers With Candy’s stock in trade was exploiting the comedic value of stereotypes, including the highly formulaic tv genre of the after-school special, and co-creator Stephen Colbert later said that Trail Of Tears was their most perfectly realized episode. For me as an avid fan of the show, this episode has always been the hardest to watch. In part this is because it goes so far in its depiction of dehumanizing stereotypes, it’s genuinely shocking. But after seeing The Thanksgiving Play, I’m thinking about it differently. As a product of the American public education system, and white American society, I never really learned how to think about the Native American culture and history. The legacy of slavery, for example, is a lot more visible and legible to me. But in a high school American history class, you get maybe one unit to cover all of Indigenous American culture; in Ohio, that included the local Iroquois nations and the entire Aztec empire. As a consumer of pop culture, you’re exposed to far more caricatures of Native Americans than real-life models. The Thanksgiving Play addresses this poverty and the sometimes absurd efforts to make up for it and laughs in its smug face. Larissa FastHorse generously invites us to share in her laughter, and for that, I’m thankful.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Abigail Weil.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.