How do Iranian artists adapt Shakespeare’s drama? The Iranian directors, Mohammad Aghebati and Mehdi Koushki, revised Hamlet and Richard II for the Iranian audience and incorporated some parts of the plot and a few characters from the original plays. The playwrights, Mohammad Charmshir and Koushki wrote Hamlet, Prince of Grief and Richard II, respectively, which veered sharply from the original texts. They were produced in 2011 and 2013 respectively. Hamlet, Prince of Grief found an exceptional opportunity to be part of Under the Radar Festival in New York City in 2013.

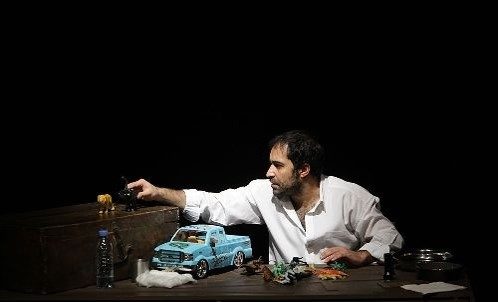

Aghebati’s Hamlet is a thirty-minute monologue, performed by a male performer, Afshin Hashemi. He performs while seated at the table in a single proscenium stage throughout the performance. The set is only a table, a chair, and a suitcase. The play is about a young student, Hamlet, who drives to go to a picnic with his family and his friends after finishing his exams.

He recites a fragmented plot of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, which is the only use of Shakespeare’s drama. The child-like figure plays with his toys and enacts the story on a countryside road. The performer opens his suitcase on the table and displays its content as his trip necessities: a saucepan, a sieve, a flashlight, a cup, and a car. Then, he takes out a bag of animal toys and cast them as his family members. His father is represented by a lion, his mother by an elephant, his uncle by a tyrannosaurus rex, and the king’s advisor by a penguin, and also Ophelia by a fragile, dead-eyed doll. The use of puppets and puppeteer expresses the fictive world of the play and also infuses some humor to saturnine mood of the play.

Hamlet, Prince of Grief is about Hamlet who is agitated and recites the story of his life. He mentions that his father and his fiancée were killed, and his uncle plans to marry his mother. At the end, he accepts his uncle’s plan of marriage. The only moment that Hamlet stands is at the end of the play when he turns his back in order that the audience sees the blood on his back as if he has been shot suggesting that whole play is Hamlet’s imagined/unconsciousness moments prior to his death.

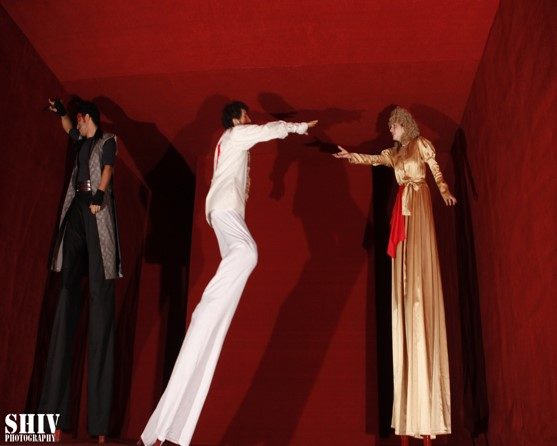

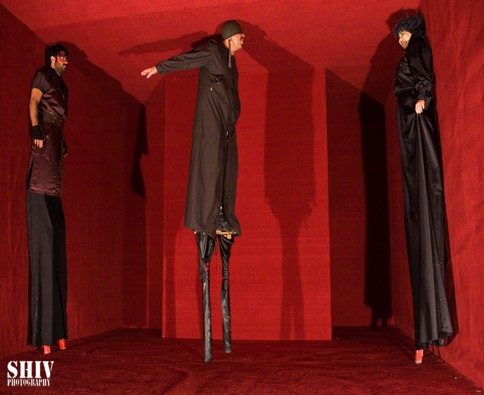

Koushki’s fifty-three-minute play includes only twelve characters from Shakespeare’s Richard II and also uses a new character, Falstaff. Reducing thirty-four characters to twelve ones affects the casting; four actresses and five actors perform the play. It is an ahistorical play based on a historical drama. For instance, a historical joke is Falstaff that doesn’t exist in Shakespeare’s Richard II. He was taken from another Shakespeare’s historical play, Henry IV. Falstaff performs a comical role throughout the play. He is fat, corrupt, libertine, and depraved alcoholic. He is somehow reminiscent of Ubu the King. In addition, the figures live in a ghastly carnival. The play has a macabre quality as the figures deceive and betray each other to their death. Death and violence are rampant. The carnival is not joyful and exuberant. The costume and make-up design evokes James Ensor’s paintings, especially “Death and Masks” and his dark vision. The setting was a single proscenium stage without any décor or accessory—only four red walls, and a back wall for creating two entrances. It was reminiscent of the abstract expressionistic paintings of Mark Rothko, especially Red on Maroon. Since all the performers wear stilts in the small room in the entire play, claustrophobic and suffocating space is implied. The tall figures are trapped in a confined place where even some heads touch the ceiling. The landscape can be seen both as a theater or a circus hall or the red box. Though Koushki sought to create the world with no geographic location, some clues to a few places including the Duke of Lancaster’s palace, Coventry, Richard’s palace, Ely place in London, a camp, and a prison are mentioned in the play.

Richard II is about Richard who has organized a carnival for his people. When Bolingbroke and Mowbray want to duel with each other, Richard exiles them from England. Then, Richard goes to the war with Ireland, and puts Falstaff in charge of his kingdom. Since Richard needs more funds for the war, Falstaff kills John of Gaunt and confiscates his lands and money. When Bolingbroke realizes that his father is killed, he returns to the country and gathers an army to revolt against Richard. The three witches foretell that Richard would be overthrown. In addition, people are sick and tired of the war and the ongoing carnival. At the end, Bolingbroke overthrows Richard, and Mowbray, who has become faithful to Bolingbroke, kills Richard in the prison. Bolingbroke’s height is over the height of the room; therefore, his back is bent in the last scene. The figures have a sardonic attitude, especially Falstaff. The figures have the title of king, queen, etc.; however, they are corrupt and do not have the qualities of excellence.

In my interview with Koushki, I found out that the idea of the carnival was extracted from Mowbray’s line: “Never did captive with a freer heart Cast off his chains of bondage and embrace His golden uncontroll’d enfranchisement, More than my dancing soul doth celebrate. This feast of battle with mine adversary” (Act 1, Scene 3). Mowbray and Bolingbroke show their excitement for their fight, which strikes Koushki to get such feeling of joyfulness and apply it to the entire play. Richard’s carnival is listless and dull, and nobody does anything except wearing the stilts, as the figures do not have enough courage to dance, make noise, and play games. They are dispirited, dejected, and feeble.

Hamlet and Richard II use the Brechtian technique of narration and a stylized acting in order that the audiences think about the worlds of the plays mainly. Hamlet’s method of acting is story telling. In Hamlet, the performer enacts statically and produces soundscape like the bird’s signings, and supplies the toys with voices. Mostly, the figures of Richard II narrate their lines standing directly toward the audiences. Moreover, there is a sense of urgency in both plays because of the abridged and abrupt scripts. The pace of the actions in both plays is impetuous. The events happen imprudently, which offers a feeling of terror. Hamlet’s territory is only the confined area at the table. His isolation in the territory implies the incommunicado of his environment. Richard II’s tall figures live in a small room, which is like a prison cell. The tallest, Richard falls down on the floor finally, and then Bolingbroke grows taller unusually. They do not see any prospect for themselves. Even if they progress and grow taller, the ceiling prevents them from improving.

Iranian audiences keep decoding the vague and unclear significations and infer meanings from them. As a result, the worlds of the plays are completed in the minds of audiences. The plays talk about the social situations in the world. In Richard II, the figures keep lying to each other to achieve more power. Aghebati centers his play on Hamlet’s position because students have historically played important roles for any sociopolitical change in any country. Aghebati and Koushki deliberately eliminate any information about time and setting suggesting that their plays do not belong or associated to any specific geographical region or society. In my interview, Koushki frames his play as “global.” In sum, the worlds of the plays imply that the true values and peace are replaced with false values and war. The notions of injustice, imprisonment, deceitfulness, terror, hypocrisy, and isolation are depicted in the plays, which invite the audiences to ponder about them.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Ali Pour Issa.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.