What has been left after all well-written dialogues, which were once deemed to be the spirit of Shakespeare’s play, were to be removed? An all-female nonverbal stage version of King Lear adapted and directed by Tang Shu-wing opens on October 28 at the Hong Kong Arts Centre in Wan Chai might be a perfect response. They showcase lethargy and grievance of life without uttering a word, but louder with body movements and expressions.

The play’s breathtakingly wild tone is set in the opening scene, where the aging King Lear is dividing his kingdom amongst his three daughters. Being fooled by the beautiful lies of Goneril and Regan, King Lear rejects his youngest daughter Cordelia’s unspeakable but true love for him. He tenaciously grabs Cordelia’s long curly hair, making her figure distortedly backbending. The servant Kent steps forward immediately. With his arms outstretched and his fingers splayed, he cries in horror.

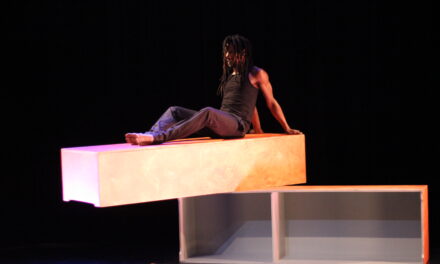

PC: Tang Shu-wing Theatre Studio

Such a stunning opening just demonstrates that even when languages were pulled out, the work still touches the core of humanity. As Tang says, ‘what exists ontologically is the human body rather than language,’. With the usage of exaggerated yet straightforward expressions, the viewers are to be equipped with a rudimentary understanding of the plot and characters’ emotions.

Besides focusing on gestures and voices, the adapted King Lear, featuring an all-female cast including Yip Tung, Lindzay Chan, and Lai Yuk-ching, is trying to break gender stereotypes as well. Tang believes that gender has become a more liquid concept especially in acting, we should be allowed to freely transgress the borders between men and women. Tang also regards his choice as a counter to the misogyny inherent in many of Shakespeare’s plays, along with the spirits of an artist. That is, always breaking free from the classical and old. As Tang does not want to do Shakespeare as a museum piece and retain all the original historic settings, he decides to explore the unlimited possibilities with the bold originality in style, making the adapted King Lear a newborn star.

PC: Tang Shu-wing Theatre Studio

What goes even further is the costume design. Characters in King Lear are supposed to be royalty and noble families 400 years ago, but they dress in very modern, shiny, and fashionable outfits today. The unorthodox costume setting by Jade Leung even gives a sense of the sci-fi genre and presents the play to be free from any time or space restrictions.

Another highlight is the textured lighting design by Yeung Tsz-yan. The various changes of multiple or single light sources, sometimes bright, sometimes dim, sometimes casting shadows with precise angles on the cursed person, adjust the emotion level of the play. A few stunning moments include someone being stabbed to death, the flaming red light instantly floods the stage, spreading uneasiness among the audience. Along with tension rises and falls, the light has been giving us a ride.

And any gaps in the show would be filled with the soaring imagination created by the audience. At some point, it echoes ‘the art of leaving blank’, originating from the technique of expression in Chinese painting, that is always leaving some spacious white on paper, so as to expand the room for the viewers’ fascination and creativity. King Lear, also vacates the dialogue and verbal conversation, letting characters, and viewers alike, just immerse in silence and their own ruminations. Those who are not so familiar with Bard’s script may find it challenging, as many complicated and always changing relationships are tightly woven together. But some obvious metaphors are well placed to assist, such as a ladder representing power that everyone desires and fights against each other, and once someone climbs upon it his enemies sooner appear to pull him down. For the crown and fame, how cruel could humans be? The answer reverberates deep within all of us.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Dawna Fung.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.