“Man can change the world with bayonet and with science, but only art can renew it, in play, in illusion.”

– Otto F. Best

This review is the second in a series exploring current New York City theatre’s interaction with the current political moment, analyzed in conjunction with theories and ideas from Carol Martin’s Theatre Of The Real. Read the first article on Heidi Schreck’s What the Constitution Means to Me here.

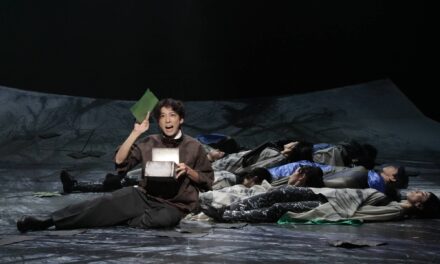

Lee Hall and Paddy Chayefsky’s Network, originally produced on the Lyttelton stage of the National Theatre, transferred to Broadway’s Belasco Theater in the Fall of 2018 and brought the National production’s director, Ivo van Hove, and Obie-winning-star, Bryan Cranston, along with it. The stage play Network was adapted by Hall from Chayefsky’s 1976 screenplay of the same title. Both the film and the play follow the story of UBS––a television network––and its fervent efforts at damage control after their lead nightly news anchor Howard Beale––played by Cranston––has a breakdown during his broadcast and announces that, in the wake of his imminent retirement, he will commit suicide on live television. This declaration sends the studio into a frenzy of damage control; the network allows him to go on the air once more to apologize to the public. Beale proceeds to go on the air and declare that his previous antics were a result of him “[running] out of bullshit” and proceeds to go on a two-minute ramble about how fed up he is with the “bullshit” of the world before the broadcast feed is cut (Hall 23). This causes a further upset in the studio and immediate remorse for allowing Beale to return to the air. Beale is immediately terminated, but when a young female program director Diana Christiansen––played by Tatiana Maslany on Broadway––working in a different division of UBS notices the ratings for Beale’s show take a dramatic uptick after his second incident, she has the idea to put him on the air again. Beale becomes a new-age prophet for the masses and develops a huge following, all of whom galvanize around his signature phrase, “I’m mad as hell and I’m not going to take this any more” (50). While the network sees this as a rating-points gold mine, the gospel of Beale is just that to Howard himself; an intervention of God. The piece is not religious topically, so this idea points rather to Beale’s wavering sanity. In light of this, UBS exploits the truthful proclamations of a deranged man for capitalist gains, as they completely reform the nightly news to become the Howard Beale show—an overproduced hour of preaching with flashy graphics resembling shows like Infowars. Beale rapidly becomes more analogous to a TV Evangelical than a Walter Cronkite, but for UBS, it gets the job done. Hall describes this piece of the story as “a man losing it, and that anger being absorbed and manipulated by a capitalist machine” (v). The piece concludes with Beale’s show losing ratings again, causing Christiansen to take evasive actions. Fueled by her greed for ratings, she and one other UBS executive arrange for Beale to be assassinated at the top of his next broadcast. The assassin––a member of the company who has been sitting alone in the front row for the entirety of the show––is successful, and so ends Howard Beale. As the audience watches aerial footage of the studio team attempting to save him, a bit of sleight of hand and excellent direction from van Hove allows the real Howard Beale to appear on stage once more and deliver the final message of the play:

And so Howard Beale became the only TV personality who died because of bad ratings. But here is the truth: the real truth, the thing that we must be most afraid of is the destructive power of absolute beliefs – that we can know anything conclusively, absolutely – whether we are compelled to it by anger, fear, righteousness, injustice, indignation. As soon as you have ossified that belief, as soon as you start believing in the absolute, you stop believing in human beings, as mad and tragic as they are… in all their complexity, their otherness, their intractable reality… The only total commitment any of us can have is to other people… This is Howard Beale signing off for the final time. (78)

The fictional narrative of Network has clear thematic roots in analyzing greed and exploitation in a capitalist society, the dangers of polarization, and the exposing of the truth. Through a critical lens of Theatre of the Real, however, the production becomes more complex. To start, since the play is an adaptation of the pre-existing screenplay, it is innately representative of something else. Paddy Chayefsky wrote the original screenplay for the film in 1976 and was, in turn, interacting with some of the most complicated pieces of modern American history––namely the Vietnam war, the Watergate scandal, and the increased role of the media in day-to-day politics. In his introduction to the play, Hall writes that “watching the movie again about ten years ago, I realized that Chayefsky’s analysis of seventies TV could equally apply to the internet… what you see isn’t necessarily what you are getting.” In this way, “Chayefsky’s satire has become almost documentary realism” (v-vi).

Carol Martin explores what it means for a story to remain relevant across multiple different moments of history in the chapter of her book Theatre of the Real titled “Seems Like I Can See Him Sometimes.” Martin tells of a piece of theatre called House/Divided by The Builders Association (TBA) that chronicles the non-fictional economic disaster of 2007 alongside the fictional narrative of John Steinbeck’s masterwork Grapes Of Wrath. The piece alternates between the two stories, in addition to the incorporation of real physical elements of foreclosed homes from 2007, to highlight the parallels between the real economic crisis and the fictional narrative of the Joad family––which in and of itself was based on the real economic disparities of late nineteen-twenties and thirties. In an interview with Richard Schechner, Marianne Weems of TBA said the union of Grapes Of Wrath and the crash narrative was obvious to them: “It became so clear that it was still such unbelievably contemporary material… it’s the same story” (44). Martin classifies this juxtaposition of real and fictional as “[producing] consciousness of the repetition of traumatic events” and “an indexical sign of the real” (161-163).

Network does the same thing by juxtaposing the fictional world of UBC and Howard Beale––which, like Grapes Of Wrath, is based on a real time in American history––with the modern setting of the play in 2018 America––where the role of broadcast news has been replaced by the internet and social media, feeding news that is often partisan, hyperbolic, or even falsified; the modern self-fulfilling echo chamber phenomenon where people only see their own beliefs in the news, thus validating them to double-down on their own opinions. Through this critical lens, Howard Beale’s final speech becomes more relevant to the 2018 climate than 1976 one, transforming Network from a parable of capitalism into a call to action against “the bullshit”––one of many terms in the modern lexicon that stands opposite to the truth.

Throughout the show, director van Hove incorporates a multitude of live video feeds and projections all across the stage––engaging the Real in an extra-textual manner. After Beale delivers his final monologue and the actors have their bows, the house lights come up and one final projection plays. The footage consists of clips from all of the presidential inaugurations from Gerald Ford––the assumed, but never explicitly specified president in the play’s fictional time––to modern day. Each president is shown swearing in, sometimes more than once if they served two terms. The afternoon I saw Network, the audience remained quiet, almost reverent, for the majority of the inauguration footage. When President Obama’s oaths were played, however, there was an eruption of supportive applause. Of course, at that point, my heart sank to the bottom of my stomach, out my feet, and through the mezzanine floor, as I knew who was next. I expected the jeers and boos during the clip of Donald Trump, but what I did not expect were cheers. Even still, amidst the tidal wave of disgust were small, isolated––but extremely convicted––pockets of support for the 45th President. In and of my own expectations of audience reaction and anticipation of who was to come next in the footage sequence lay my personal polarized political beliefs––blinding me from at least trying to see from both sides of the aisle. There I was, having just heard defamation of polarization from Network’s protagonist, engaging in a display of polarized-partisan agendas. Van Hove had force-fed us our own hypocrisy, leaving me asking: What happens now? Do we fight each other? Do we make up? Or neither. We all proceeded to stand in the moment of tension, leave the theatre, and return to our lives. The placement of real video footage drawn from “Donald Trump’s America”––the current political moment of 2018, not 1976––piggybacks on the audience’s deeply coded opinions of these US Presidents in order to exemplify the very issues decried in the two-hour long fiction narrative prior. Van Hove creates a theatrical moment independent of the actors and script, but completely dependent on the real people in the audience, providing another “indexical sign of the real” and forcing us to confront our own realities in real time as they relate to the current political moment. This final moment of the production serves as a test for the audience, to see if they really did hear Howard Beale’s cry against polarization––ultimately in an effort to support the production’s goal of impacting the audience’s minds with Beale’s parable.

I will concede, the play at times becomes so focused on Cranston’s technical ability that it transforms into more of a feat of strength-esque exhibitionist fantasy for Breaking Bad fans and less of a well developed character-driven narrative. Personally, I don’t mind that all too much. I love Breaking Bad! Moreover, in light of this, it is important to emphasize the exploration of Network as a parable. Religious parables are filled with archetypal characters depicting greed, sin, altruism, etc. Network is yet another exploration of these ideas but in the political-media paradigm of the modern climate instead of BCE Israel. It is the exploration of a system where sources of entertainment––namely social media and news outlets––are influencing global political dealings in ways unseen. It is time for the entertainment industry to take a more active hand in fighting the abuse of these media tools to gain unjustified power.

Augusto Boal said, “All theater is necessarily political because all the activities of man are political and theater is one of them” (ix). There is a need for a call upon the highest pillars of commercial artistic society to capitalize on the political nature of the theatre, as those who are perpetuating structures of marginalization are already capitalizing on the theatrical nature of politics. Ivo van Hove has put his best foot forward in making Network an unwavering step in the right direction. Network’s final extension in the Belasco Theatre runs through June 8th.

Works Cited

Boal, Augusto. Theatre of the Oppressed. New York: Theatre Communications Group, 1985. Web.

Hall, Lee. Network. Faber and Faber Limited, 2018. Print.

Martin, Carol. Theatre of the Real. Ed. SpringerLink. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK: Imprint: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013. Web.

Schechner, Richard. “Building the Builders Association: A Conversation with Marianne Weems, James Gibbs, and Moe Angelos.” TDR (1988-).3 (2012): 36. Web.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Lucas M. Kernan.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.