George Bernard Shaw was a theatrical superman. A critical attack dog, as well as a creator of problem plays both pleasant and unpleasant, he invented the drama of ideas, under the motto: “If you do not say a thing in an irritating way, you may just as well not say it at all.” Misalliance, his 1909 play about class relations, family, and feminism, is a fine example of his intellectual sparkle and makes for a stimulating evening in the theatre. Having successfully revived GBS’s Widowers’ Houses (in 2014) and The Philanderer (last year), the Orange Tree’s Paul Miller now takes on this Shavian rarity.

Misalliance is set in Hindhead, Surrey, in the country house conservatory of Tarleton, a self-made draper who has made millions from the sale of female underwear. This upwardly mobile businessman, an exemplar of the rising bourgeoisie, lives with his wife, sensible son Johnny, and daughter Hypatia. She is engaged to Bentley “Bunny” Summerhays, the young and rather effete son of Lord Summerhays, a former colonial administrator, and the match of two people from different social classes is clearly a misalliance. But not just because of their different class backgrounds: while Bentley is lazy, spoiled, and neurotic, Hypatia is active, resourceful and alive to the possibilities of life.

When, in the middle of the play, a light aircraft crashes into the family greenhouse, two new arrivals raise the temperature of the play: Joey is the glamorous upper-class pilot and his passenger is Lina Szczepanowska, a Polish acrobat and feminist who immediately makes her presence felt. Then another visitor arrives, a mystery man from the lower classes who questions Tarleton’s moral standing in no uncertain terms. He is an out and out socialist, who boldly if comically announces: “Rome fell, Babylon fell—Hindhead’s turn will come.” As all of these outsiders show, the solid middle-class family is actually a fragile affair, and the idea of a misalliance applies to almost all of the characters.

GBS’s play is a comedy of both manners and ideas. The writing is amusingly self-aware, with Hypatia complaining that all everyone does is “Talk, talk, talk, talk,” but then, what talk it is. The playwright, who can often be a loquacious bore, is here nimble and fleet, with ideas tumbling out and falling over each other on the stage. At one point, we are asked to think about free public libraries, at another about Europe; then there’s stuff about social equality and a running joke about book reading. The play criticises the rigid conventions of Edwardian respectability and the uncaring relations between parents and children. In its plea for youth to understand, and therefore forgive old age, there is a fairness and balance that means that GBS offers no solutions to the dozen or so moral quandaries he presents.

Today, perhaps the most troubling of these is sexual abuse. Tarleton, for all his energy as a philanthropist, bibliophile, and autodidact, is exposed as an adulterer and philanderer, using his power as an employer to seduce younger women. Because his wife seems to accept this, he never quite gets his comeuppance. Likewise, Lord Summerhays is attracted to the young Hypatia and makes a fool of himself. This results in some wry comedy, but the attraction, or not, between older men and younger women, as playwright Elinor Cook suggests in her program note, leads to the behavior of the Harvey Weinsteins of our age. As she points out, “The status quo has a horrible habit of reasserting itself.”

In the play, Hypatia represents the female force that will disrupt the sexual and familial status quo. For her, the family is a prison. “Men like conventions,” she observes, “because men make them.” She wants to be an “active verb,” for something to happen, and to be able to be independent. Her instinctive desire to do better than her current engagement to a weak young man is bolstered by the arrival of Lina, a fully fledged feminist whose parting speech emphasizes in its directness and simplicity—“I am strong; I am skillful; I am brave; I am independent”—not only the suffragette creed but also the feminism of the whole 20th century. In her dealings with men, she offers a sharp antidote to sentimentality and soppiness.

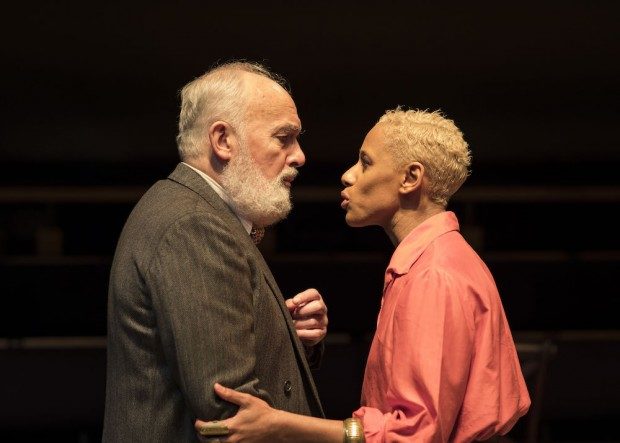

Miller’s wonderfully entertaining revival of this rather rare GBS play, simply designed by Laura Hopkins, brings out both the comedy and the fairness of the original, leaving us to make up our own minds about who is good, who is right, and what is wrong. As Tarleton, Pip Donaghy brings an attractive energy to a man whose lines include “It’s not bad language—it’s only socialism.” His daughter Hypatia (Marli Siu) has an appealingly sunny openness and bright directness while his down-to-earth wife (Gabrielle Lloyd) and philistine son (Tom Hanson) are good in support.

Simon Shepherd gives Lord Summerhays a justified dignity, while Rhys Isaac-Jones lends a high-pitched voice to the highly strung Bentley. Luke Thallon and Jordan Mifsúd perfectly embody the opposite classes of the aristocratic aviator and the lowly clerk. Casting Lara Rossi, a black actress, as the Polish Lina adds a reminder of Empire to her excellent portrait of the self-possessed, disdainful, and intelligent outsider. Thought-provoking, playful and fun, the play is a joy to watch, but the fact that the Orange Tree still has no Arts Council grant is little short of a scandal—you can imagine what GBS would have said about that!

Misalliance is at the Orange Tree Theatre until January 20.

This post originally appeared in Aleks Sierz on December 15, 2017, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Aleks Sierz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.