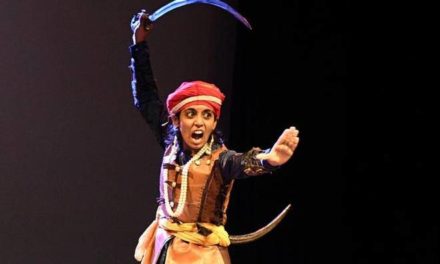

Three gramophones affixed to angular wooden boxes stood tall, almost animal-like, on wiry metal legs. Nearby, colorful patches of outrageous, yet sleek costumes nearly lept off the stark white mannequins they adorned. Angular theatrical models, small, but magnificent, could easily be imagined to contain the large-scale, black-and-white photos of theatre productions that loomed from the walls.

Exhibition view, Enrico Prampolini. Futurism, Stage Design, And The Polish Avant-Garde Theatre, curated by Przemysław Strożek, Łódź Museum of Art (Łódź Muzeum Sztuki), 2017.

The inspiration for Enrico Prampolini. Futurism, Stage Design, And The Polish Avant-Garde Theatre, an exhibition curated by Przemysław Strożek at the Łódź Museum of Art (Łódź Muzeum Sztuki), was a painting: Tarantella, by the pioneering Italian Futurist of the show’s title. This bright, dynamic, and geometric deconstruction of Italian folk dancers was a fitting invitation to freely explore the colors, textures, and shapes of the artfully curated drawings, film clips, objects, paintings, and publications that peeked out from an open maze of separated gallery walls. It is rare to see the artifacts of theatre history presented in a way that feels as live as the art form itself—and to have the chance to explore Futurism from a Polish perspective.

Exhibition view, Enrico Prampolini. Futurism, Stage Design, And The Polish Avant-Garde Theatre, curated by Przemysław Strożek, Łódź Museum of Art (Łódź Muzeum Sztuki), 2017.

As noted by Strożek in the show’s catalog, Prampolini—also a sculptor and painter who worked in realms as diverse as advertising, film, and mural art—developed his own term for his practice as a scenographer. “Scenotecnica,” in the artist’s native Italian, could be translated into English as “sceno-technics”—a design-based theatre “technology,” almost like architecture, that was rooted in the Futurist vision of creative mechanization. Its rejection of a more illustrative approach to theatre design was exemplified in his work with the brief-lived Théatre Du Pantomime Futuriste, which performed in Paris and several Italian cities in 1927 and 1928. Prampolini described its all-encompassing, rhythmic expression of performance as “the geometric splendor of the ultra-modern motor.”

Exhibition view, Enrico Prampolini. Futurism, Stage Design, And The Polish Avant-Garde Theatre, curated by Przemysław Strożek, Łódź Museum of Art (Łódź Muzeum Sztuki), 2017.

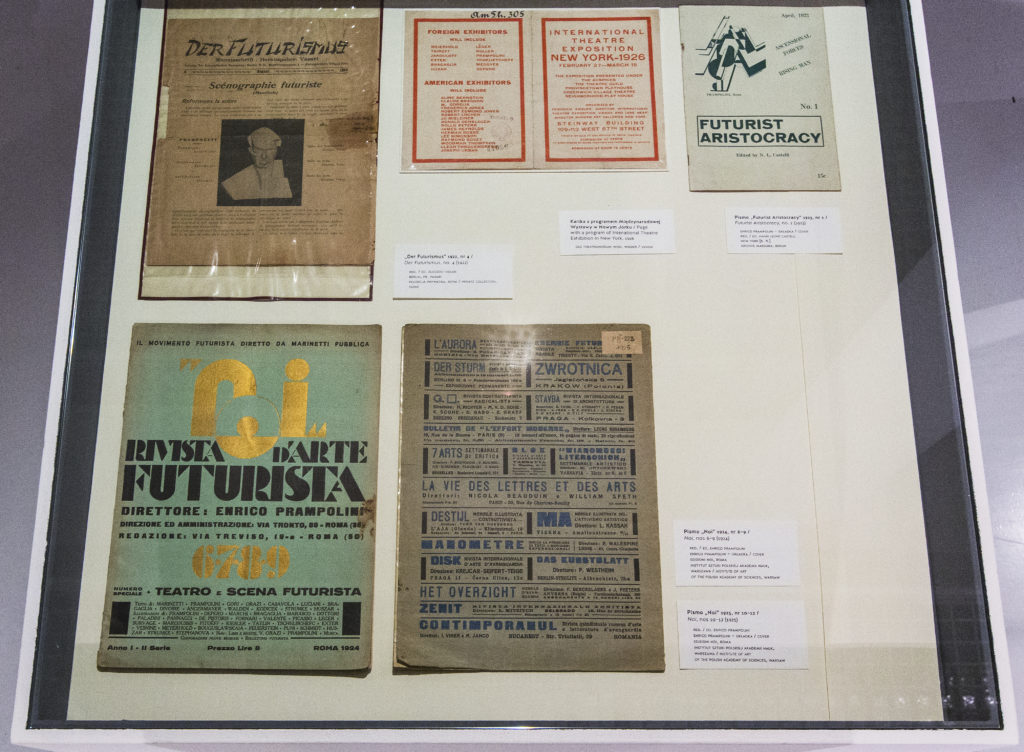

A “total” art form in conversation with Wagner’s Gesamtkunstwerk, Prampolini’s “sceno-technics” resonated with the aftereffects of the Polish “monumental” tradition that had emerged in the wake of the First World War, out of the Romantic and Young Poland movements before it. Strożek’s extensive research shows that through exhibitions, performances, and publications, avant-garde artists and writers in Poland encountered Italian Futurism directly, as early as 1909. By the end of that decade, collectives such as “Bunt” in Poznań, the Kraków Formists, and the Polish Futurist circles in Kraków and Warsaw had adopted—and rebelled against—the ideas of Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and the members, like Prampolini, of his Futurist group. This formed a fundamental part of the Polish artists’ own search for new ways to create and conceive of the theatrical experience, particularly after 1918, when their country gained its independence after more than 100 years of foreign occupation.

Materials from Enrico Prampolini. Futurism, Stage Design, And The Polish Avant-Garde Theatre, curated by Przemysław Strożek, Łódź Museum of Art (Łódź Muzeum Sztuki), 2017.

Strożek’s exhibition was the first ever to directly link Italian and Polish Futurism in the context of theatre, as well as the largest of the work of Prampolini, or any one Italian Futurist, outside of Italy to date. Strożek’s thoughtful selection of Italian, Polish, and other European works—by Anton Giulio Bragaglia, Maria Nicz-Borowiakowa, Władysław Strzemiński, Ruggero Vasari, Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, Rougena Zátková, and others—allowed visitors to trace these creative connections for themselves. One of the most important of those presented was between Prampolini and the Polish stage designer Andrzej Pronaszko—renowned for his collaborations with the influential director Leon Schiller, a relationship begun in this period in Warsaw. A look into Prampolini’s model for a”Magnetic Theatre”—more of an all-encompassing, technology-driven design machine—was an apt culmination of the show’s content and form.

Exhibition view, Enrico Prampolini. Futurism, Stage Design, And The Polish Avant-Garde Theatre, curated by Przemysław Strożek, Łódź Museum of Art (Łódź Muzeum Sztuki), 2017.

Enrico Prampolini. Futurism, Stage Design, And The Polish Avant-Garde Theatre was presented from June to October this year as part of the current centennial celebration of the avant-garde in Poland (100 Lat Awangardy W Polsce). Prampolini was himself a curator, of the international avant-garde stage-design show at the Milan Triennale in 1936—only five years after the radical “a.r.” collective launched the Łódź Museum. The group of artists and poets had hand-picked and developed its collection, which many of the works in this show were from, as they secured donations—of what are now some of the world’s most renowned works of art—from their own network of fellow avant-garde artists across Europe.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Lauren Dubowski.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.