When asked to pick one word that describes the city of Hong Kong, Romanian performance artist Manuel Pelmus opts for “spiraling.” Staying for a few weeks in the city to open his show at art institution Para Site, he notes the intensity of life here.

By spiraling, he is referring to the sense of energy and vertigo one feels moving about the city, upwards and downwards, and how the layers of architecture feel disorientating and endless. He expresses these sentiments from a barren art space offering a birds-eye view of Victoria Harbour, adding that he plans to spend the afternoon exploring more of his host city.

Experiencing Hong Kong is exciting for him: the city provides quite a contrast to his native Bucharest, not to mention tranquil Oslo, which he now calls home. But Hong Kong is not without its parallels to his place of birth. As citizens of a former satellite state of the USSR, Romanians understand some of the anxieties and existential crises that come with having a history intertwined with a geopolitical behemoth. Even today, almost 30 years after the fall of the Soviet Union, the specter of Russian influence and encroachment looms large in the Baltics and Eastern Europe, and the memories of life under the yoke of communism have yet to fade for Pelmus’ generation.

Hong Kong’s increasing enmeshment with mainland China produces tensions that feel familiar to Pelmus. Among them are uncertainties around national identity and feelings of cultural suppression–alongside a sense of foreboding as to what the future will hold. His latest work draws on these tensions, exploring assertions of identity that come in the form of bodily actions, many of which reference political movements pertaining to Hong Kong and Taiwan’s quest for cultural autonomy.

But, while the region’s complex relationship with mainland China serves as a strong thread in his interrogation of the region’s performance art history, Pelmus is quick to note this aspect isn’t the be-all-and-end-all of the piece. It also incorporates gestures that speak to social issues, including movements that invoke Hong Kong’s many scavenging, cardboard box collecting poor. And though the work is pegged to the city, it is not without wider relevance. Part of the aim of the piece is to invite audiences to draw connections between local histories and wider solidarity movements, tapping into an idea of universal solidarity and shared collective experiences.

Born in 1974, Pelmus trained in Bucharest, where he grew up under Nicolae Ceausescu’s authoritarian regime. The decision to make a career out of dance was one he and his parents believed might offer a way out of the country, alongside being a good fit for him. Pensive, sincere and expressive, but without airs, Pelmus is easy enough to engage with and has a thought process containing a level of nuance and complexity that makes every answer to a question on his work and ideas paragraphs long. That he would cross into the world of conceptual, research-based art seems like an inevitability.

After completing dance school in Bucharest, Pelmus earned a scholarship to study contemporary dance in Hamburg, later joining a company as a professional dancer. Wanting a greater sense of autonomy and creativity, he shifted into the world of contemporary dance and later established himself as a performance artist and choreographer.

A seminal moment in his career was a 2013 work, An Immaterial Retrospective, produced alongside artist Alexandra Pirici, which turned heads at the Venice Biennale. It involved a group of plain-clad dancers in a sparse white space re-enacting works from previous biennales continuously, in a way that reframed passages of the history of modern art pertaining to the institution.

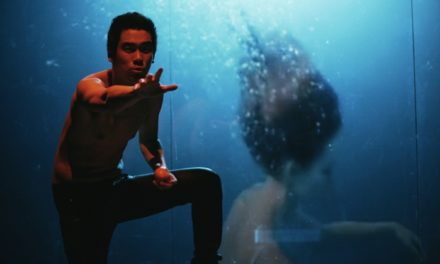

The anti-express rail procession on January 18, 2010, Hong Kong–Photo by Benson Tsang–Image of performance–courtesy Eddie C. Y. Lam–Image Art Studio.

A key interest of Pelmus’ is looking at the way art, particularly object-less art can be reworked in new contexts, creating subjective takes on art history that invite audiences to reimagine the spaces they are exhibited or performed in. This is part of a wider movement in art theory that deals with the place and purpose of museums and exhibitions and how art exists within them in the contemporary age. Pelmus brings up various critiques on the role of the art space today, describing how some theorists argue that the increasing individualization of humanity, glued to their smartphones and living increasingly atomised existences, reflects itself in the way people engage in artworks at exhibits and museums.

Enjoying art has become an increasingly solitary experience, theorists argue, while others posit that a way forward might be to strive to counteract this atomisation by invoking collective, community-building art experiences. Rather undogmatically, Pelmus suggests that a purpose for performance art can be to help foster communal experiences.

This is one factor that drives his piece at Para Site, which has been created specifically with Hong Kong audiences in mind, drawing on their own history of performance art–although he says it will also resonate with wider audiences interested in expressions of social movements and how they might be conceptualised in an experimental, choreographed exhibition context. Called Movements In An Exhibition, the piece draws on gestures of social action and protests from recent Hong Kong and Taiwanese history. It is the result of months of research into the recent history of performance art here that have a generally activist bent, or else respond in a considered way to historical events impacting all layers of society.

The piece, which will be performed daily by a rotating team of eight dancers at one of Hong Kong’s oldest and most daring independent art institutions, involves gestures referencing the leftist riots of 1967, which grew from a labour dispute at a plastic flower factory into an anti-colonial uprising, alongside more recent passages of fraught history, including the Umbrella Movement, and a fragment drawn from Zuni Icosahedron‘s repeated work based on Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years Of Solitude.

Woven into this framework are also references to social movements in Taiwan, which grapples in its own way with its complex identity and its relationship to mainland China. Another reference Pelmus has incorporated into his work is an exhibit in a private house on Kennedy Road, where performance artist Robert Chui moved in with his belongings and invited audiences into his life as it existed in this space, striving to counteract the barriers between performer and audience.

Encompassing months of research, which drew particularly heavily from the increasingly ample resources at Asia Art Archive, Pelmus hopes that the show won’t just be engaging for those with an art history bent as fervent as his. “Anyone is welcome–it’s quite direct,” he says. “The wider public can get something out of it because it’s about bodily postures. [You] don’t have to have an education to relate to it. There are songs, lyrics, Taiwanese dialects, kinds of melodies, it’s also easy to follow, and there’s something for all ages to engage with.”

Part of what makes it particularly accessible is the fact that audiences are welcome to enter and leave the performances whenever they want. More crucially, the piece provides a space where corporeal expressions of belonging and identity can be enjoyed in a way that brings people together, and an invitation to contemplate the role of an art space and how it can exist to contain and help preserve ephemeral history.

Pelmus regrets that he can’t stay long in the city. He is soon heading back to Europe, where time passes much more slowly. But he is eager and curious to return to Asia. “Hong Kong is fast-paced,” he says. “It’s too easy to tell people to slow down, but what I would like is for them to spend a bit of time together.”

A History Of Movement runs until March 4, 2018, at Para Site. Click here for more information.

This article was originally written by Sarah Karacs for Zolima CityMag on December 20, 2017. Reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Zolima CityMag.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.