Empty Gregory’s coffee cups and PureLeaf bottles reside on a table, Trader Joe’s bags are against the coat rack. String lights are hung with haphazard care, and, perched beneath the coffee table, there are books by Moshfegh, Playbill, and Brecht. The small room is messy and cozy, welcome, and, within its detail-oriented minutiae, instantly recognizable. This isn’t just the home of someone young. It’s the home of a young artist. In this case, a brash, extroverted, insecure actor, working on her solo show about breast painting.

So begins Sophie McIntosh’s cityscrape. This inaugural production of Good Apples Collective follows the tumultuous friendship of two artists in New York City: Kitt, a novelist struggling to make it past 200 pages, and Kat, an actress working to marry self-worth with the righteous study. The irony of their names is not lost in this relationship. In parallel to the iconic chocolate bar, Kitt and Kat are perfectly fit, twin souls with a telling crack stretching between them. When they end up roommates—mutual friends of the perpetually absent Eileen—the crack waits for human fragility and fallacy to snap in half.

Mia Fowler and Simone Policano in cityscrape. PC: Nina Goodheart

In totality, cityscrape feels oddly Brechtian (ironic, once again, when considering Kat’s love of the man’s work). We, as an audience, follow this dysfunctional dynamic through its blossoming, its breaking, and its open resolution through a series of chronological vignettes. McIntosh’s wordplay balances exposition and observation with ease: one feels so very welcomed into this space, able to bare their heart alongside these young women. The back story is compelling, never draining, and statements on humanness arrive with subtlety in their bravado. Kitt and Kat are two louder-than-life characters commanding intimacy; it’s this very juxtaposition that gives them power. Brecht meets Sir Chloe. Shakespeare meets Sweater Weather.

Dialogue is not the only place where cityscrape excels. In fact, though the exchanges are captivating, I’d argue it’s not the strongest part of the show. Silent action provides even more. McIntosh’s script meets director Nina Goodheart’s vision in a sublime way: the foreshadowing of mental disorder and addiction, of possession and implosion, begins from the very moment we meet these two ladies. Whether it’s Kitt’s migration to the bar cart or Kat’s growing pile of carrots, the seeds of disaster are planted with masterful understatement. As an audience, one’s subconscious knows exactly where this train is headed, and it makes the wreck all the more wrenching.

The partnership between Goodheart and McIntosh epitomizes what makes this play so successful. I was blown away by the ensemble effort of this artistic team. Red Guhde’s precise attention to detail in set and prop design allowed the eye to gain insight with every object seen. Paige Seber’s impeccable lighting design provided a myriad of environments without once shifting physical set. Cora Cicala’s sound design, from Kitt-Kat’s playlist to the soundscape of Brooklyn, gave a real sense of grounding and intimate knowledge to a play rife with big ideas. And Saawan Tiwari’s costume design was a spectacular study in color theory and subtle hints. The marriage of all four—seamless, might I add—gave a full world, an effect I marveled at more than once. The technical design felt both inevitable and highly innovative.

Simone Policano and Mia Fowler in cityscrape. PC: Nina Goodheart

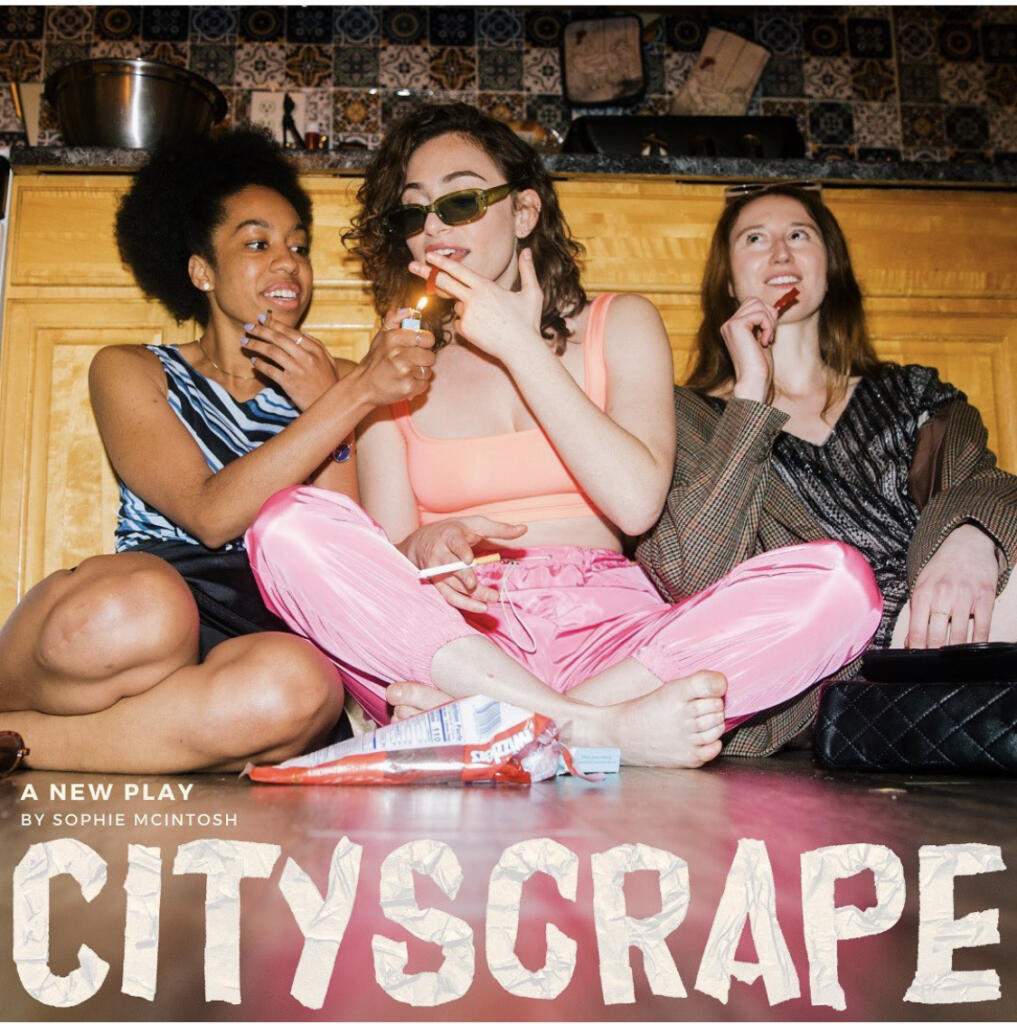

The actors lived up to this expectation and beyond. Simone Policano (Kat), in particular, was luminous. Capturing the intricacies of vulnerability and pain within a boisterous character can prove difficult, and Policano navigated the divide effortlessly. Kat felt beautifully fragile, painfully alive. Mia Fowler (Kitt) played Policano’s counterpart with skill. The author-artist felt a bit too staccato at first, but the establishment of this pattern led to a lovely realization of catharsis in becoming verbal. Fowler’s youth lent itself well to uncertain discovery. Marianna Gailus joined for a short period of time as wealthy-and-wanting Eileen, providing an eye to the outside world.

It is worth noting here that the cast and creative of cityscrape is composed entirely of marginalized gender artists. This allows for further nuance. For instance, the bi-lighting utilized on Kitt and Kat seems to symbolize a relationship teetering on the edge of platonic: whether it’s romance or codependent possession, the audience can decide. Though both young women royally screw up, they are neither perpetrators nor victims only. The denouement is not a catfight, either, but an open-ended question: are they better or worse apart?

In short, cityscrape is a highly atmospheric, bombastic, envelope-pushing piece, highlighting our deepest intimacies in a loud proclamation. Its humor may be niche (New York artists, prepare to feel confronted), and you may want to see a little more of Eileen, but, all in all, McIntosh and Goodheart’s inaugural piece is a heart-clenching joy.

Mia Fowler, Simone Policano, and Marianna Gailus in “cityscrape.” PC: Good Apples Collective

To see more from Good Apples Collective, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Rhiannon Ling.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.