The popularity of vampires has endured since Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Bride of Corinth (1797) and Bram Stoker’s better-known Dracula (1897), based on a Transylvanian folk myth. Stoker’s novel set many of the literary conventions for the genre: drinking fresh blood, the constant search for new (young, female) victims, the male vampire as a lonely outsider, superhuman strength and agility, immortality, and many more.

Black Swan Theatre Company’s production of Let the Right One In, directed by Clare Watson, revisits the vampire story and stays true to many of these tropes, using copious amounts of blood. But it has a major difference: the vampire is a teenage girl.

Let the Right One In is Jack Thorne’s adaptation of the novel by John Ajvide Lindqvist (Låt den rätte komma in) published in 2004, a year before the popular teenage vampire saga Twilight. It was made into a Swedish-language film in 2008, and a Hollywood adaptation followed in 2010. The stage version premiered in Scotland in 2013 and became an international hit after its transfer to London’s West End.

Linqvist began his career as a playwright and screenwriter, and Let the Right One In is a versatile story that can be told in any genre. At its core, it is a love story for our times. The vampire, Eli (Sophia Forrest), while able to scale walls and kill people at will (all the victims are men), still wants to share her life with someone. The reasons are practical, such as helping her to feed without detection, but as the play unfolds, she seems to want to have a genuine friendship with 12-year-old Oskar (Ian Michael), and cares enough about him to push him away so he cannot discover her terrible secret.

Rory O Keeffe, Alison van Reeken, Clarence Ryan and Ian Michael in Let The Right One In. Photo: Daniel J Grant

This is in stark contrast to the mature man, Harkan (Steve Turner), who arrives in the Swedish town of Blackeberg with her. At first, it seems he is her father, but we soon learn he is in love with her, and he wants her to love him back.

Even though Eli is several hundred years old she has the body of an immature girl. The sexual overtones between her and Harkan are disturbing, to say the least. This is echoed by the overly clingy actions of Oskar’s mother (Alison Van Reeken) who cuddles up on the sofa or in bed with her son after one too many red wines.

As the story unfolds, our perceptions change and Eli shows her true nature. She has an old and very manipulative head on young shoulders, and her kitten-like helplessness comes with fangs.

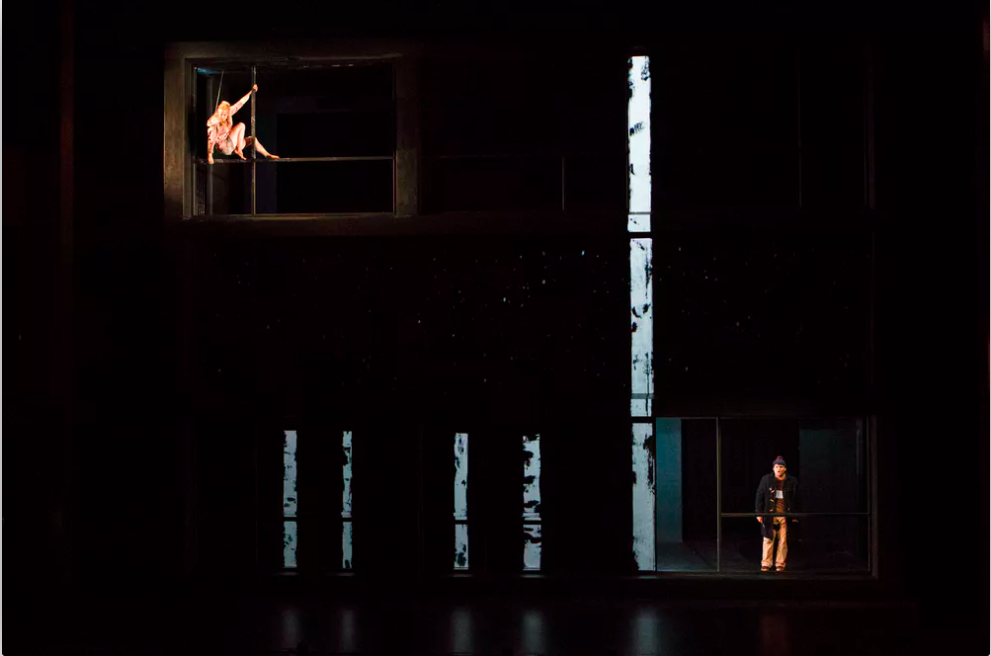

For her directorial debut with the company, Watson has teamed up with Bruce McKinven (designer) and Richard Vabre (lighting) to create a visually stunning, three-story set that supports the isolation and loneliness of the main characters. Stark flat surfaces evoke the concrete walls of an apartment or the smooth segments of a Rubric’s cube, and serve as a backdrop for Michael Carmody’s projections of falling snow or bare trees under a dark winter glow. Rachael Dease’s dramatic and often ethereal soundtrack completes the mood.

There are excellent performances, particularly from the young cast members. The two thugs who bully Oskar, Jonny (Rory O’Keefe) and Micke (Clarence Ryan), are at times quite terrifying. Both are comfortable in their physicality and navigate the demanding set with ease. Forrest is also exceptional and exhibits the movements of a gravity-defying vampire with grace and agility. Oskar is body-shamed by the bullies, and Michael’s gestures and stance poignantly show his pain and his fear of his persecutors.

Sophia Forrest as Eli and Ian Michael as Oskar. Photo: Daniel J Grant

The other members of this ensemble cast (completed by Stuart Halusz and Maitland Schnaars) put in fine performances in multiple roles, making the most of their function to move the story along with minimal character development. This is perhaps the result of taking a novel-cum-film and making it into a play. The scenes are all relatively short and jump across time and location; they are framed around physically dramatic action, making the dialogue seem quite sparse; and the coming and going of many minor characters.

The constant sliding to and fro of the nine screens to reveal a new scene is at times slow and becomes predictable despite attempts to disrupt this with projections, music, and occasional choreography. The contained spaces work well for the claustrophobic rooms of the apartment block, but the set loses the isolation of a town surrounded by a wild forest. Sitting near the front of the stalls my view of the upper levels was not ideal and occasionally the onstage lighting was blinding.

Nonetheless, this is a fine debut for Watson and demonstrates a bold vision for the company she now leads. She is unafraid of expanding theatre’s appeal to a younger, screen-driven audience through plays such as this while keeping the regular and possibly more theatrically sophisticated patrons entertained with strong narrative and visual spectacle. Her previous experience is varied but her work in theatre for young audiences has served her well here. The troubled relationships of the young characters are touching to watch, and their energy and emotional lives on stage are captivating.

Watson has programmed the complete 2018 season, titled The Conversation. It aims “to catalyze and contribute to the big conversations” we face at local, national and international levels. It is an opportunity for her to provoke, engage and stimulate an Australian audience and I look forward to it with great interest.

This post originally appeared on The Conversation on November 22, 2017 and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Vivienne Glance.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.