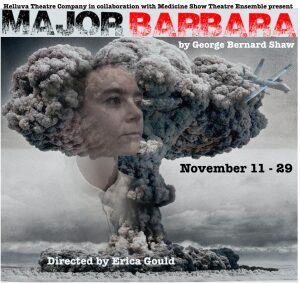

Helluva Theatre Company—newly formed under the mission to produce plays from the traditional canon that aren’t often seen, and in effect offering actors a spectrum of style beyond contemporary popularity—has ambitiously chosen George Bernard Shaw’s Major Barbara as its inaugural production. The dialogue-heavy, two-and-a-half-hour play set in 1906 was resurrected by Helluva Theatre in part for its parallels to our current societal conversation concerning the relationship between wealth and power (and the complex dilemmas of morality therein). One hundred years later, the force of Shaw’s language accomplishes the desired impact.

Major Barbara is reimagined at the Medicine Show Theatre with full utilization of the space, with what could be described as minimalist, mostly effective set design. The actors impressively carry the significant order of presence and intense dialogue called for by Shaw’s work. Associate Artistic Director Zoe Anastassiou stars as Major Barbara, with Artistic Director John Martello playing her father. Supported by a cast with an expansive range of experience, the differing approaches to the craft make for delightful moments of highlight interspersed between the anchors of magnitude dictated by the plot.

In the first act, we’re situated immediately and intimately in the Undershaft family’s wrought preparation to receive estranged father and wealthy armaments manufacturer, Andrew Undershaft. Dynamics of coercion are accentuated with focused physical staging, a strength that director Erica Gould has gained recognition for throughout her career. In simple and defined strokes, we’re clear that we’re following a high-stakes narrative with far-reaching implications, no less than suggesting father-figure to metaphorically represent god-figure.

Act Two exposes the various iterations of madness. Under Martello’s guidance, the Undershaft father slides seamlessly down the tonal register from jovial to dark—claiming, for example, that the “love of common people” is “an illness.” In one exchange, his response to a list of virtues is to matter-of-factly state the method by which each virtue can be twisted to exploit workers. Exploration of power dynamics continues in the compelling, fully believable portrayal of Bill Walker by Jared Culverhouse, along with the carefully-detailed character portraits delivered by Laralu Smith and Richard Brundage (playing Rummy Mitchens and Snobby Price, respectively). Set in the Salvation Army shelter, the characters wrangle with each other and themselves, snared in the angry confusion of shame and offense. It’s both engaging and saddening to watch the players pretzel into deeper and deeper rhetorical contortions, self-pressed to defend their individual belief system.

Allegiance to instilled belief system is carried to term, even after disproven in one of the play’s numerous philosophical jousts. With fully disclosed partiality for philosophy and specifically the Ancient Greeks, I appreciate Shaw’s integration of ancient thought through Adolphus Cusins (Barbara’s fiancé and professor of Greek, played endearingly by Richard Emerson). His station is subject to scrutiny like every perspective in Major Barbara—the father patronizingly refers to Adolphus as “Euripides”—but in my opinion, including ancient philosophy in the foreground is a significant factor in the play’s longstanding relevance. A favorite moment in the production was the climactic philosophical battle between Andrew Undershaft and Adolphus, by which point Helluva Theatre had transformed the black box space into a 360-degree, whitewashed interior of the Undershaft armaments factory and positioned the audience in the center. Physically placed in the middle of the heated argument, the analogy of audience as populous, caught between and trying to keep up with the powerful who debate their fate, had profound resonance.

Major Barbara is an exercise in inspecting nuance of a point of view—one any modern citizen would be served well by. It gives introspective voice to facets of anxiety that can feel beyond articulation, while reminding of the irrationality borne from fear (perhaps encapsulated most memorably with the line, “hatred is the coward’s revenge for being intimidated.”) Helluva Theatre’s timely choice of production, skillful stamina, and range of style all project a promising forecast on their beginning tenure in the theatre community.

Playwright: George Bernard Shaw

Director: Erica Gould

Off Off Broadway at Medicine Show Theatre, 549 West 52nd Street, New York, NY

First published by The Atticus Review on November 28, 2016. Reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Rachel E. Diken.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.