In the closing moments of Richard Maxwell’s Samara, the audience is plunged into near-total darkness. A low-creeping fog passes through what had been the playing space in a gesture that feels at once cleansing and indicative of a restless spirit on the move. We hear the gravelly voice of a man describing the night he had to explain to his young daughter what it means to die. The fog clears and the bare stage is illuminated in dozens of different aspects as the stage manager runs through all previous lighting cues in quick succession. The play doesn’t simply end; it expires after a series of protracted final exhalations, a long letting-go that might seem excessive or indulgent if Samara were not itself an off-kilter allegory of ends and endings great and small, and of the ways in which we try to stave them off.

The title of the play is a place name, an origin point that inspires allegiance, nostalgia, and fear each in turn. “Back home,” a philosophically drunk character opines, “we knew what the rules were…It was clear. Oh, those were some times, weren’t they…Samara was a good place. And who knows, maybe it will be good AGAIN.” The line evokes Donald Trump’s campaign slogan and the droves of “forgotten” rural Americans who wore it emblazoned on t-shirts and trucker hats, but Samara is set in a rugged outback territory of the mind. It takes days to travel between outposts where provisions can be procured, and when the rains come one can get stranded in certain parts of the frontier for months.

Samara begins with a murder. A young messenger is owed wages for his work, but his employer is owed, too, and can’t pay up. The messenger kills his boss, assumes control of the debt, and sets off to collect. He finds the aforementioned drunk and the manan who owes him. They have taken themselves “off the map.” To avoid paying, the manan shoots the messenger, regrets doing so immediately, and sets out to return the body to Samara. The manan meets the messenger’s mother by chance on the road and is revealed to be her son’s murderer. After much wailing and gnashing of teeth, the mother pronounces that the manan stole “their” culture. “They want their culture back,” she says to the manan, “You. You owe.” It is not specified whose culture was stolen by whom, but the lighter skin of the actors playing the manan and the drunk and darker skin of those playing the messenger and his mother conjure any number of colonialist scenarios.

Richard Maxwell generally directs his own work, and the distinctive qualities of his auteurship have frequently eclipsed his authorship. He encourages his performers to cultivate a relationship to language that has been described as “deadpan,” but this reductive description belies the infinite subtle gradations of freedom and vulnerability opened up by his approach. Maxwell performers often move through their insistently provisional environments giving the impression that they are “marking” their lines and blocking rather than fusing with their characters on a deep, psychological level. This leaves them exposed in ways that transformative actors who dissolve into their roles are not. The work of such actors is to efface evidence of artifice and anxiety, but Maxwell performers acknowledge and even emphasize these elements of the theatrical encounter. In embodying characters, they present situations, actions, and feelings, but they do not do all of the feeling for the audience. Being occupied with their own private emotional journeys, performers leave audience members alone to trace theirs. The experience is always revelatory: curiously solitary and refreshingly uncoercive.

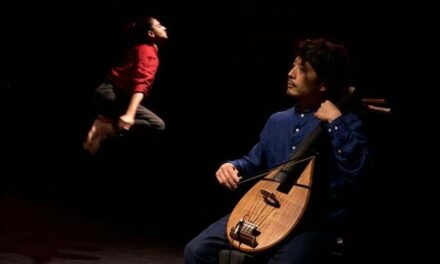

Samara is directed by Sarah Benson, under whose tenure as Artistic Director Soho Rep has become perhaps the most vital and intrepid theater in New York. Benson is a very fine director and a much more full-blooded one than Maxwell, so observing how a Maxwell play behaved under her guidance promised to be intriguing, and Samara does not disappoint. She stages Maxwell’s text on a severe set made entirely of plastic milk crates and gives the roles of both composer and on-stage narrator to Steve Earle, real-life hero of so-called “outlaw” country music. Other members of the eclectic cast include Vinie Burrows as the Mother, Paul Lazar as the Drunk, and Becca Blackwell, whose gender-indeterminacy in the role of the Manan complicates the story’s questions about patrilineal inheritance and responsibility. Benson encourages a more connected, emotive approach to character than Maxwell, and it changes the way we hear his text, which never allows us to forget its writtenness. Indeed, Samara might be his most self-consciously literary play yet. Debt and its collection drives the plot, but also hovers over the action as a layered metaphor for love, family, culture, and life itself. What do we owe our progenitors? What do they owe us? How much of what we have and who we are can truly be said to belong to us? How much borrowed? Stolen? The most cherished mythic American values—individualism, self-reliance, reinvention—have little currency in Samara. Instead, all of existence is figured as a loan that must eventually be paid back. With interest.

In Benson’s hands, the more soaring moments in the text do not feel as foreign, as received, as they do when Maxwell directs, and this brings the audience and the performers onto the same plane. We are more absorbed, less aloof and reflective, and this suits the lush, lyrical text, even if it leaves one craving some quiet time alone to read and reread the play after the curtain call. What Samara makes abundantly clear is that in addition to being a consummately unique man of the theater, Maxwell is also a true poet whose works, like Shakespeare’s, deserve to be staged in as many different styles as there are directors.

Samara

By Richard Maxwell

Directed by Sarah Benson

Original Music by Steve Earle

Produced by Soho Rep

Mezzanine Theatre, A.R.T./NY Theatres

April 4-May 7, 2017

New York City

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Jessica Rizzo.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.