Set in the leafy grounds of Holmwood House in Glasgow’s Southside, Simon Starling and Graham Eatough’s performance At Twilight: A play for two actors, three musicians, one dancer, eight masks (and a donkey costume) was a successful example of the Common Guild Gallery’s commitment to putting visual art and theatre into innovative dialogue. The performance, which combined dance, music, and drama, was striking for its structure, for the way in which W.B. Yeats’ Noh-inspired, symbolist play At The Hawk’s Well was placed within the framework of an artist’s talk or public lecture. In keeping with Starling’s rhizomatic mode of working in Project for a Masquerade (2010), a piece that At Twlight organically grew out of, the staging sought to explode the autonomous confines of the fictional world. Instead, the aim was to open up Yeats’ modernist text to a series of historical, biographical and aesthetic entanglements. The play’s dramaturgy was constructed around the interplay of three different performance modes: the presentational style of the lecture-performance in which the two actors (Adam Clifford and Stephen Clyde), dressed in judo suits, took on the personae of the play’s creators, Graham Eatough and Simon Starling; the representational aesthetic of dramatic theatre when the same actors told the story of W. B. Yeats’ and Ezra Pound’s tense, competitive relationship at Stone Cottage in Ashdown Forest during World War I; and, the strange hybrid style for At the Hawk’s Well that fused the hieratic, anti-naturalism of Symbolist performance with what is perhaps best described as a DIY Noh aesthetic.

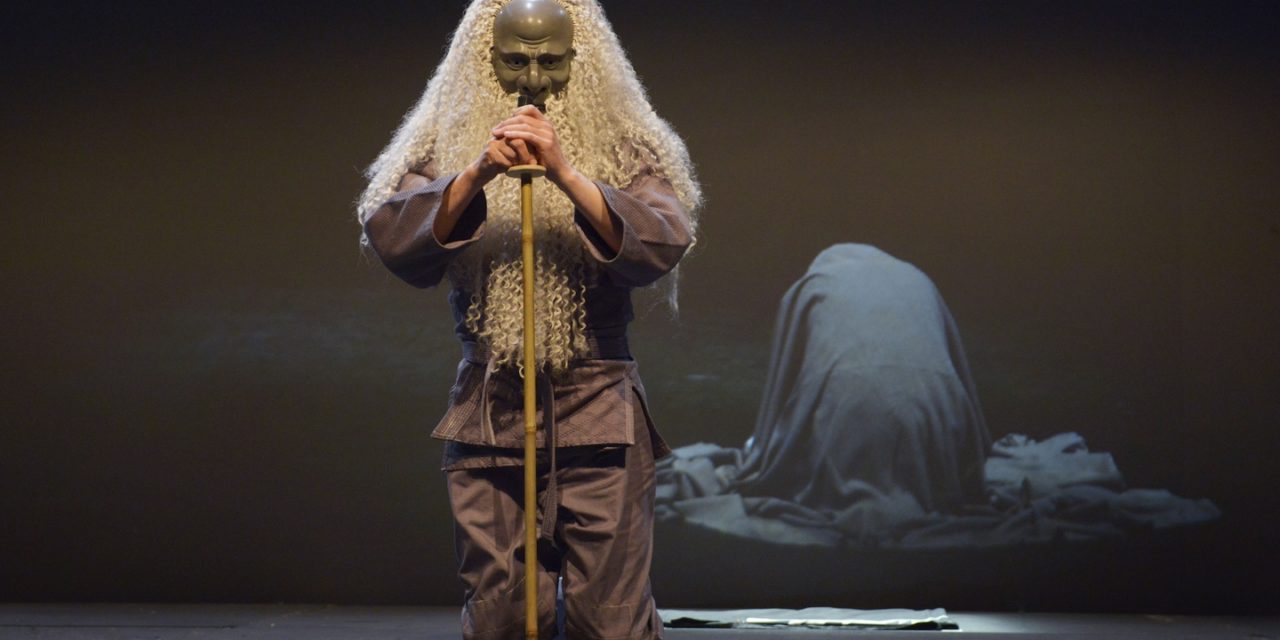

In keeping with the simplicity of both Symbolism and Noh Theatre, the stage itself was largely left bare, except for a number of blackened, ‘blast trees’ on which the masks of the principal protagonists and artworks of the drama were hung: W. B. Yeats, Ezra Pound, The Old Man, The Young Man, the Hawk, Nancy Cunard, Jacob Epstein’s Rock Drill, and Michio Ito, a Japanese dancer who danced the part of the Hawk in the original production in 1916. One of the intriguing (but uncanny) aspects of performance was the way in which the masks acted as both artwork and prop, artifacts that formed part of an exhibition of the work at the Common Guild, and yet had a very different ‘life’ when on stage. As opposed to the usual logic of props, which is largely, to disappear reticently from view, here the masks constantly drew attention to themselves. This interrupted the naturalism of the performance and highlighted how theatre always functions as a medium that shows itself in the very act of showing, and so cannot help but interrupt its own theatricality.

The interruptive quality of the masks, the sense of disjunction they caused, complemented the Symbolism of Yeats’ play. At The Hawk’s Well is a work in which the evident artificiality or stylisation of the performance demands a different form of attention. Here the point is not to identify with the psychology of ‘ real’ characters, to get under their skin, so to speak, in order to learn about their deeper motivations. On the contrary, the primary concern is to produce a kind of ‘complex seeing’ – the phrase is Brecht’s – in which the ‘distanciation’ produced by the mask creates a greater intensity of imagining. The entire logic of Symbolist performance, in other words, is to remain on the surface, to insist on theatricality, and so produce a new kind of tragic experience that avoids the excesses of dramatic theatre.

A commitment to theatricality is evident too in the relationship between the characters of Simon and Graham. Whereas ‘Graham’ is desperate to ‘play’ and constantly tries to get the Simon persona to move out of his comfort zone and perform, the latter responds by anxiously holding on to the lectern and sticking doggedly to his pre-written text. The humour inherent in this relationship is reiterated at the very end of the play. Here the two actors don the same donkey costume that had appeared so congruous at the very start of the performance and tell the story of how A.A Milne, the author of Winnie the Pooh, composed his book at the same time as Yeats and Pound were musing on the aesthetics of Noh in Ashdown forest. Finally, then, in the dénouement, the audience gets to ‘know’: the pantomime donkey is Eeyore, a central protagonist in Pooh’s adventures.

The reference to Eeyore and the ensuing dramatization of the story of his tail is no mere act of whimsy. Not only does it place Yeats’ play at the centre of a dense and ever expanding nexus of connections, it also undercuts the lofty and elitist modernism at work in Yeats’ thinking and democratizes the work, replacing autonomy with relationality, ‘genius’ with context.

There are a number of reasons why theatre is the perfect place for Simon Starling. First, it is a space of transformation in which objects take on a life of their own; second, it is a space where the theatrical image produces thinking by asking spectators to make connections between words, gestures, and materials; and finally, and perhaps most importantly, it exists as a space of haunting, a site whereby the thing that is depicted, is always doubled by what is not there. So in this play or piece of dramatic storytelling that did so much to contextualize Yeats’ works historically and personally, there was always an excess of signification, always a ‘more’. Watching the play unfold in Glasgow, at twilight and on the cusp of late Summer/Early Autumn, I was reminded of the influence at At The Hawk’s Well on Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot; Ezra Pound’s fascination with Mussolini; and, of course, of the Easter Rising in Ireland that took place in 1916, the same year in which At The Hawk’s Well was written and which Yeats depicted in his poem ‘Easter, 1916’. Fittingly, and beautifully, all of these connections were left unspoken, and hovered like spectres in the air. I could have made hundreds more.

This article was originally published on http://www.e-tcetera.be/. Reposted with permission. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Carl Lavery.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.