The long-term collaboration between the China National Peking Opera Company (Guojia jingju yuan) and Sinolink Productions continues to be a success, as they carry forward their project to bring Chinese traditional theatre to the London stage.

This year, the London audience has been presented with a superb production of a Peking Opera play entitled The Emperor And The Concubine, which was performed at Sadler’s Wells Theatre on October 19 and 20, 2018.

With a plot largely based on historical events and characters, this play portrays the amorous relationship between Emperor Xuanzong of the Tang dynasty (618-907 AD) and his favorite consort Yang Yuhuan, who was one of the Four Beauties of ancient China and was better known by her acquired nobiliary title of (Yang) Guifei.

The play starts with a long musical introduction whose Western-style dreamy melodic tones suggest an atmosphere of idyllic bliss, well suited to anticipate the romantic content of the story. However, presently, a female voiceover announces that said love story will meet a tragic end. The audience is therefore prepared to expect a terrible fate to destroy the romance of the emperor and his concubine, as befits a (Western) tragedy.

Photo credits: Sinolink Productions

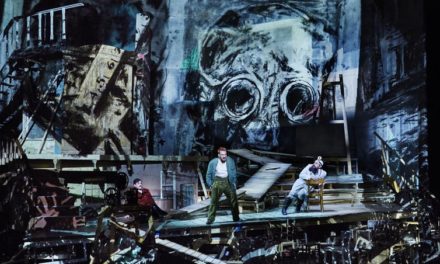

Still, before such worse befalls the couple, the audience can feast their eyes on a series of visually and aesthetically magnificent scenes, mainly aimed at celebrating the astonishing attractiveness of Lady Yang (played by Li Shengxu), which is enhanced by her spine-tingling singing and delightful dancing and, not least, by the surrounding kaleidoscopic performance apparatus that is typical of Peking Opera. Quite noticeably, and deviating from the convention of Peking Opera, this production employs quasi-illusionistic scenography, with naturalistic backdrops and a diverse array of stage props, including a bathtub, a tree, and a rock. Particularly noteworthy moments are when she dances for the emperor (played by Yu Kuizhi), when she takes a bath at the thermal spa, and when she worships the moon goddess with the stars Vega and Altair on the Chinese Valentine’s Day (Qixi). Furthermore, the emperor never ceases to laud her good looks, using a rich natural and supernatural linguistic imagery, whereby he likens her to a phoenix, a fairy, and a lotus flower. Even potentially disturbing scenes, such as Lady Yang’s death, are highly aestheticized thanks to the interplay of visual and aural elements, including frequent changes of lighting and graceful pantomime.

Photo credits: Sinolink Productions

Indeed, a general sense of aesthetic beauty pervades the whole play, actively taking center stage, while the actual plot is overshadowed, coming across as less important. The latter contains some interruptions and ellipses, whereby key turning points are skipped, briefly narrated by a chou (clown character; played by Chen Guosen), who performs the emperor’s attendant Gao Lishi. These gaps can be a bit confusing but help speed up the rhythm of the play, which is quite slow-paced and repetitive, especially in the first part. The second part, instead, is more varied and tense, as it features some spectacular combat scenes as well as Lady Yang’s suicide by self-hanging. The couple’s love story, which has already known a few crises, is definitively brought to an abrupt end by the concubine’s coerced suicide as she is accused by the imperial army and by the populace of indirectly favoring the outbreak of the An Lushan Rebellion and of distracting the emperor from his duties.

Photo credits: Sinolink Productions

Still, contrary to any previous expectations, this is not the end, for, after many long years of mourning and separation, the emperor and his concubine are finally (and incredibly) reunited, as she welcomes him in her heavenly palace upon his death. At the conclusion of another visually delightful scene, the audience hears once more the romantic musical theme that was played in the beginning plus the words spoken by the female voiceover. Yet, this time the word “tragedy” is obscured by the sound of bells and an atmosphere of triumphal joy fills the stage, while audiences clap their hands in exultation.

Curiously, the Western-sounding music is deployed to heighten the circular structure of this play, which is predicated on the typically Chinese dramaturgical principle of “separations and reunions” (beihuan lihe), culminating with the “great reunion” (da tuanyuan) in heaven.

As there is no substantial difference between the natural and the supernatural worlds in ancient Chinese culture, for they are both part of the same, holistic reality (the Dao), The Emperor And The Concubine is, indeed, a tragedy with a happy ending.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Letizia Fusini.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.