London fringe theatre is underfunded and under-resourced, but it often produces work that is more exciting than the mainstream. Much more. In particular, venues such as the Theatre 503, the Finborough, The Yard, and The Bunker are now staging shows that are emotionally profound, and that sparkle both with ideas and with a confident theatricality. Sarah Page’s Punts, which originally had a reading at the Finborough’s Vibrant 2016 festival, is a good example. It is irresistibly appealing in its wit, its truth, and its brio.

The plot kicks off with disarming simplicity. Alastair is a rich fortysomething legal eagle, married to Antonia, who is a housewife. They live in a beautiful London house with Jack, one of their three sons, who has a learning disability. He is 25, and a virgin. Like any young man, he thinks a lot about sex, and the guys at the local rugby club apparently talk about nothing else. To give him a helping hand, his parents arrange for him to watch “female-friendly pornography,” and then they hire a classy twentysomething prostitute, Julia, to pop his cherry. But the introduction of sex and money into this nice middle-class family has powerful, and unexpected, results.

The arrival of Julia, an articulate middle-class sex worker who has lots of experience with people like Jack because she volunteers as a care worker, overturns a lot of clichés about prostitution. Likewise, the anxiety of Alastair and Antonia that their son should fit in more, and be more like a “normal” man, is mildly parodied in their project of getting him laid. The opening scene, in which Antonia prepares Jack for Julia’s visit (selecting his best shirt, making sure he’s washed his privates) is both funny and a small masterpiece of exposition. As the 85-minute play develops, its main themes are revealed: parental control, consent to sex, and the ability of people with learning disabilities to make choices.

Punts contrasts two ways of dealing with disability. The first is from inside the family. Both parents have learned to live with Jack, and Antonia, in particular, is very defensive about any changes in his behavior. But this desire to control runs into the parents’ attempts to control his desire: what happens when Jack likes Julia so much that he wants to see her again? Are the parents over-protective? How can Jack be more autonomous? The second way is from the outside the family. Julia, in a scene so touching you scarcely dare to breathe, even while you’re laughing, relates to Jack with such intelligent care that you instantly want to give her an OBE.

What’s so special about Page’s writing is its delicacy and lightness of tone, as well as its comic sassiness. She manages to gently mix deep emotion with genuine hilarity, yet always with a smooth touch. Once you accept the basic premise of the plot, it develops elegantly and logically, pushed along by both character and ideas. Julia brims with bravado but, like many sex workers, she is emotionally bruised and her frankness barely conceals a vulnerability of her own. The difference, it turns out, between her and Antonia, both mothers, is one of class, and the issue of selling your body in order to make money is central to the story.

Page’s text is partly based on interviews with sex workers, and it defies many of the media images of crackheads and streetwalkers. At the same time, there’s a critical comparison between one woman who sells her body for cash and another that sells both body and mind for a cushy life. As in so much modernist drama, marriage is here compared to legalized prostitution. Both Alastair and Jack’s masculinity raise other questions about control, evident in the amusing episode of the sex game that the parents play at one point, and about the sexism of everyday life. Although this liberal household is quite enlightened about porn, it’s hard to accept the casual denigration of women that is not far from the surface of their privileged existences.

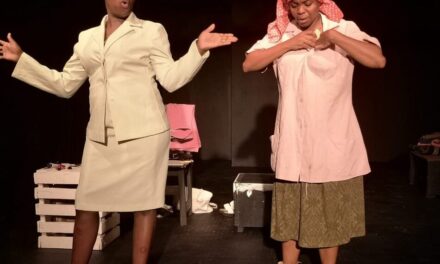

Jessica Edwards’s well-paced production, for Kuleshov Theatre, has a liberatory feel about it and builds up to a hopeful ending in which the characters discover new possibilities opening out for their lives. Amelia Jane Hankin’s minimalist set, with its strip lights, is ideal for fizzing scene changes and helps keep the show’s intimacy alive. Christopher Adams is beautifully restrained as the truth-telling Jack, while Florence Roberts’ Julia is both empowered and empowering. Graham O’Mara and Clare Lawrence-Moody play the parents with just the right mix of care and frustration (with each other as much as with their son). Punts — the title refers to the clients of prostitution — is a very absorbing, superbly written and marvelously well-played piece of new writing. Something very special.

Punts is at Theatre 503 until June 24.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Aleks Sierz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.