I.

So when a man pinches my ass or grabs my boob or another tries to rub his dick against my thigh … you want me to go on stage and share this by just saying: he tried to do/say something inappropriate?’

–BuSSy monologue, performed in 2012

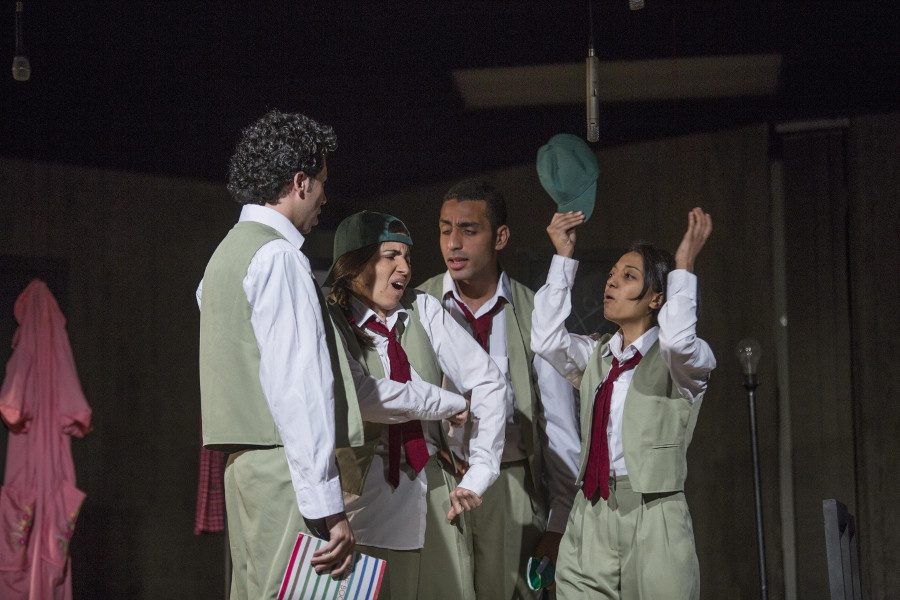

I am the director of the BuSSy project, a performing arts project that documents and gives voice to untold stories about gender in different communities in Egypt. These stories are later shared on stage by their tellers in performances usually referred to as ‘testimonial theatre’, since we document and take raw stories to the stage. Women share experiences of harassment, rape, gender discrimination, honour killing, forced marriage, female genital mutilation, motherhood, domestic violence, child abuse, mass sexual assaults, and others. Given the nature of such testimonies, our constant battle is how to reflect the reality as truthfully as possible and – quite literally – get away with it; we have been subjected several times to multiple forms of censorship by various state and private entities in Egypt and abroad.

Trying to challenge this equation is often futile, but many continue to do so, BuSSy included. This essay will consider the ways that the project has, since its inception, navigated the murky waters of censorship both from outside and within.

II.

The BuSSy project was originally founded in 2006 by a group of female students at the American University in Cairo in reaction to a performance of the Vagina Monologues in Cairo the year before. The name we gave the project is a play on words (BuSSy in Arabic means: look, and in English it looks similar to a word commonly used to describe female genitalia), and it is also one of the reasons why a renowned cultural venue in Cairo, Sakia or El Sawy Culture Wheel, refused our request to rent the space to perform. It is also the same reason that we were refused to perform at Georgetown University, Washington D.C., USA, after the professor who had invited us emailed us, saying: ‘I would love to find a way to bring “BuSSy (we have to discuss that name) Monologues” to my university.’ She later explained that she thought the name and the clear play on words would be offensive to an American audience.

Nowadays, we at BuSSy are very careful when we consider the language we use to write the project name and whether or not we mention the original inspiration behind its creation. The word ‘vagina’ in Arabic is unspeakable; it is hardly ever used except in medical textbooks, so much so that many are not even familiar with the term. But aside from this issue, associating a local theatre project with the Vagina Monologues (as an American theatre project) produces a certain number of negative associations that would often affect how the project was received and our ability to connect with local partners in different cities and local communities around Egypt. As such, we only mention the reason behind the name or the meaning of it when we know we are not going to be shunned as a result.

But the issue of our project’s name has become the least of our problems. During the early years of the project, most of the stories we performed were in English. As the years went by, we steadily shifted to telling more Arabic stories, after agreeing that the project’s mission is to reach a wider audience. By 2010, all the stories we performed were in Arabic, with a couple in English.

Throughout the project’s history, we have come across stories we felt we could not perform. We received one such story in 2010 about a female domestic cleaner who lives in a very poor neighbourhood in Cairo, with ten family members in one room. The story is told by one of her clients, who discovered that the cleaner had decided to wed her son to her daughter. We received two similar stories before this specific one, but decided until then that incest is a topic that is too much of a taboo to be told on stage. But this third time, we felt we could no longer ignore the narrative. After all, the project is meant to act as a channel through which stories are collected from the public and passed back to the public, without setting agendas or selection criteria other than the fact that the story has to be real and related to issues of gender.

There was another story we received in 2010 that we struggled with: a beautiful piece written by a young lady about her vagina, and the names her friends and family use to refer to the vagina and how that makes her feel. We decided not to include it in the final performance; there was a lot happening that year, after all. We were moving the project outside the university and trying to establish it as an independent project, unaffiliated with any establishment, and preparing for the first performance mostly in Arabic, outside of university premises. We already had several other stories that we foresaw might cause problems: testimonies of premarital and marital sexual problems, incest, taking off the veil, a chronic harasser. We decide not to include it, and I often look back at this story and doubt if the decision right or wrong.

But then I am reminded of our first battle with state censorship back in 2010, when we performed at the Cairo Opera House on a small wooden built stage in the cafeteria right next to Creativity Centre after being refused a space to perform in several private and state-owned venues. After the first night, several members of the audience, journalists, and employees in the Cairo Opera House complained to different authorities about ‘inappropriate’ content in the performance. We learned that members of the moral police, state security, and tourism police had spoken with the person in charge of the space and informed him of the possible repercussions should the performance continue unedited. We took the decision to censor the already censored script in order to perform it. After the show, we told the audience that we performed half of the script because the other half had been censored. Yet, in truth, the performance had gone through a number of rounds of censoring, beginning with our own – that story of the woman who talks about how the names for the vagina make her feel. In the end, I feel like we might have made the right decision at that time.

Of course, we were often engaging in our own form of self-censorship by that time: the university also tried in 2008 and 2009 to take copies of our scripts so that they could be submitted to censors for the approval of any performance. We would remove words or phrases that would cause any form of discomfort to the audience or replace them with a ‘bleep’ or a ‘teeet’ sound. Once, we told an entire story with bleeps; but even this was labeled ‘inappropriate’ due to the topics the performance tackled despite the ‘appropriate’ text.

Coincidentally or not, ‘inappropriate’ was the same word the director of the Hanageur Theatre inside the Cairo Opera House used to describe BuSSy’s last show 500s in 2015. This was a performance of stories by teenagers in Egypt, scheduled as part of the Hakawy Theatre Festival. But during rehearsal, a technician flagged our performance as offensive and the director asked for a private performance before the public showing so as to view the content. As a team, we decided against it and expressed that this would be another form of censorship, which we opposed. The next day, just a few hours before the performance, we were banned from performing in the Hanageur, ever.

This is the problem when it comes to self-censorship: it is one of the most commonly practised yet rarely spoken of types of censorship and a process that most artists in Egypt engage with, either knowingly or not. We battle with this challenge everyday at BuSSy: Do we mention the Vagina Monologues or not? Do we keep those words or not? Do we put this story out or not? Do we perform there or not? But when it comes to how we deal with censorship, we still don’t really talk about it. As Mona El Shimi, a BuSSy story-teller who has been part of the project since 2009, notes that a self-censorship is an act of negotiation. As she explains: ‘If I self-censor, then I don’t give the full truth but I’m more likely to be listened to, but if I don’t self-censor and I give the full truth, I won’t be listened to at all. So let me give a distorted version of the truth so I don’t lose everything.’

Anyone working in the scene of performing arts in Egypt will tell you that it all boils down to this equation in the end: perform ‘appropriate’ content and get better chances for shows in state and privately owned theatres, and thus reach more viewers. Or else perform ‘inappropriate’ content in very limited venues and with limited access to a viewership.

In 2010, we wondered: if we were received this way even when practicing self-censorship, what would happen if we didn’t? Quoting El Shimi again: ‘We keep giving up parts of the truth so that we will be accepted and listened to. We try to get something better than nothing. We do it out of a fear of losing. But I guess the only people who end up getting most or all of what they want are those who are willing to risk it all.’

In the case of BuSSy, though we have come a long way, our hands are still tied. We are unable, for instance, to work on all the gender issues present in the society. We are unable to come close to dealing with homosexuality since it would jeopardize the entire project – by law homosexual acts are banned and the regime have recently embarked on one of the biggest crackdowns on the community of homosexuals in Egypt.[1] Performing or publishing a story of a homosexual would instantly put the teller and the project team in danger of being arrested, which in turn jeopardizes the project’s continuity.

The negotiation of self-censorship, in this sense, is ongoing. Even BuSSy’s 2015 performance of 500s was labeled ‘inappropriate’ because of the use of ‘inappropriate’ words and the tackling of ‘Inappropriate’ content. Not only were we talking about masturbation; one of the characters actually said the word on stage. After the ban of 500s, we showed it in a private venue. It later travelled to Portsaid and Assiut. In both cities, we decided to take votes on whether the audience wanted to see a censored or uncensored show. In both cities, the majority voted for an uncensored performance. After the Assiut performance bystanders and people who had been present in the venue during the show but didn’t come to watch it, directly and indirectly, threatened the team.

III.

As a result of the Hanageur ban in 2015, I have been thinking about the stakes of censorship today from both sides of the coin: the perspectives of the individual and the state. In Egypt, though state censorship laws and regulations have not changed, the 2011 revolution has affected self-expression and encouraged several artists to challenge both the state- and self-enforced limitations that often prevent an artwork from reaching its full potential. BuSSy is but one part of an entire art scene that has silently and collectively embarked on a similar journey in different ways.

On a personal level, I remember during the protests of 2011 and later on, that I would go down each time to the crowd and test how far I would walk towards the front line. It was as if part of me wanted to see how far I could push myself beyond a certain fear. Later, during conversations with friends, I realized it wasn’t just me who was drawn into the protests this way: many others, not just from Egypt, described the same thing. The question is simple: how far can I go this time and get away with it? Self-censorship, to me, is very similar to this experience. You either choose to stick to one place or you decide to walk into the unknown.

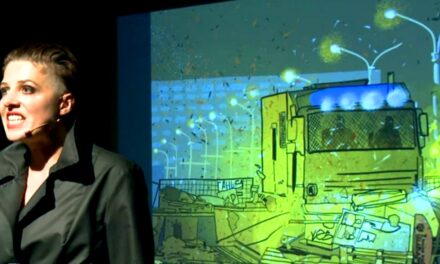

In February 2011, a week after Egypt’s revolution, a few members of BuSSY started brainstorming for a new performance: Tahrir Monologues (Stories from Egypt’s Revolution). We used the same mechanism for story collection and documentation as we did for BuSSY, except for one little detail: we did not censor inappropriate words, many of which were said in the scripts by police officers arresting or beating up protestors performed by storytellers who collectively agreed that cutting out those words would affect the story. So we decided to keep the words and read out a disclaimer before each performance:

This performance is for +18 only. The performance contains some words and phrases which some may find inappropriate or offensive. We have decided to keep those words out of respect to the author of the story and in an attempt to truthfully pass on the story to you.

I read it out during the first performance in May 2011 in the Rawabet Theatre and held my breath. An hour and a half later, the audience applauded and kept chanting slogans from the protests. Several members of the audience came up to me and said though they disagreed about keeping the inappropriate words, they respected our way of doing things. Of course, not all disagreements were that friendly, but despite this, we managed to pull off more than 30 different performances in Cairo, Alexandria, Minya, and Marsa Matrouh, all uncensored and with the disclaimer. We performed in different venues, one of which was state owned, and got away with it.

IV.

In 2012, we stopped performing Tahrir Monologues (Stories from Egypt’s Revolution), and went back to working on BuSSy and stories of women in our community. We staged our first uncensored performance of BuSSY in 2012, with testimonies about harassment taking place during the protests on Tahrir Square. Most of the stories were brutal, to say the least. The storytellers themselves had a hard time rehearsing with the actual words. I remember my father suddenly showing up and walking into the performance (thanks to social media, the family knows everything). I did not see him after the performance and he never spoke about it and neither did I, though I often wonder how he must have felt seeing me stand on stage and say the word ‘fuck’ in Arabic. The performance was followed by an open mic session during which members of the audience were invited to go on stage and share their own stories. The open mic lasted for hours and the stories shared were equally as brave and daring as those shared in the performance. Courage is sometimes contagious, it seems: it just takes one person to break a barrier for others to follow.

The first performance was followed by a couple of other uncensored performances, though one performance we did censor at the time was performed on the subway carriages of Cairo (we would go onto a carriage, do a 15-minute performance, then leave and take another). For BuSSy’s subway performances, we decided to perform a couple of relatively light stories that contained no words or phrases that might encourage anyone to beat us up. The positive feedback outnumbered the negative. By the end of the day, we came away with stories shared by various women on the subway after each performance and a lot of prayers and blessings. Still, we almost got beaten up.

In 2013, we were invited to perform in Sens Interdits Theatre Festival in Lyon, France. We used this opportunity to test our ability to challenge our own boundaries. How far could we go in a place where the old risks aren’t there? The process of creating and performing the piece Look at Me – stories about the female body from childhood to adulthood – in Lyon and later in Cairo was very insightful: one of the most liberating performances I have ever worked on. Yet, when we went back to Cairo and prepared to show the performance there, it was painful to realize, admit and accept our limitations, so often self-inflicted. For the Cairo show, we sat down and carefully examined the script and censored bits here and there from the original performance in Lyon. We performed for one night, did not publicize it, and invited only a handful of people. That was it.

V.

As this piece was in editing, I received some alarming news. The American University in Cairo committee, which co-manages The Falaki Theatre (built and owned by the American University in Cairo) with Ahmed El Attar (renowned theatre director and founder of Emad Eldin Studio) has recently decided that a censorship permit is required for performing in the Falaki Theatre. The space that once witnessed and encouraged The BuSSy Project now refuses to host it without censorship. From the 2010 ban of BuSSy to the events of 2015, performances were labelled ‘inappropriate’ and banned. Self-censorship made no difference to what seems to be an inevitable outcome.

But if something has changed between then and now, it would be that we have become braver, more experienced and better connected with our supporters and audience. In 2010, BuSSy accepted censorship and performed a slaughtered script. In 2015, we refused to be censored in any shape or form, issued a press release about the ban and launched a campaign on our social media about it. Outcomes are not always the same, after all.

[1] Patrick Kingsley, ‘Egypt’s Gay Community Fears Government Crackdown,’ The Guardian, 17 April 2014 http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/apr/17/egypt-gay-community-fears-government-crackdown.

This article was first published on www.ibraaz.org. Reposted with permission of the publisher. Read the original article here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Sondos Shabayek.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.