With this year’s Egypt National Theatre Festival drawing to a close, a closer look at the featured plays reveals a return to literary adaptations and mystical works, as well as an apparent fascination with student theatre.

Shaman, Toqoos Al-Esharat Wa Al-Tahwlat (Rituals of Signs and Metamorphoses), Al-Toqoos (The Ritual), and Qawaed Al-Eshq Al-Arbeoon (Forty Rules of Love): all are plays based on Sufi tradition which have had great success. Is Sufism becoming a trend? It has been incorporated into various directors’ works, all of whom relied on the spiritual atmosphere to attract audiences.

“We must learn to comprehend the circumstances in which we live. The state is attempting to spread tolerance and interreligious dialogue, thus these Sufi plays work well within their strategy. I cannot, however, claim that this fascination with Sufism directly stems from the authorities,” says Ahmed Khamis, critic and member of the National Theatre Festival’s selection committee.

“Adel Hassan’s play, for instance, which was based on Elif Shafak’s best seller, The Forty Rules of Love. [The play] has done an impressive job of capitalizing on the work by creating a great marketing campaign on social media. The idea of tolerance and spirituality resonates with contemporary audiences, which serves to explain the success of Said Soliman’s play, Shaman. The director has, for some time now, dedicated himself to the creation of Sufi plays,” adds the critic.

The same themes of tolerance and peace are also present in the play Youm An Qatalo Al-Ghenaa (The Day They Killed Singing). The play is more abstract and doesn’t directly delve into Sufi rituals, it rather draws inspiration from such rituals to profit from the trend. This trend is even visible among the Palace of Culture’s productions in different regions.

“Artists in the various governorates of Egypt often imitate prevalent trends in the capital,” notes Khamis. This year’s edition of the festival has also been marked by many adaptations of literary works.

“It is quite a positive phenomenon. The original works, both novels, and poems are mature and encompassing artworks. They help theatre artists in their creative process, they provide them with a solid base. This does not, however, mean that we should undermine new Egyptian playwrights,” he adds.

Mohamed El-Malki’s play, Lambo, draws inspiration from Abdel Rahman Al-Abnoudi’s poem. Playwright Mohamed Amin used the poem as a starting point, then proceeded to build on it and create an original work, addressing social justice in the wake of the revolution.

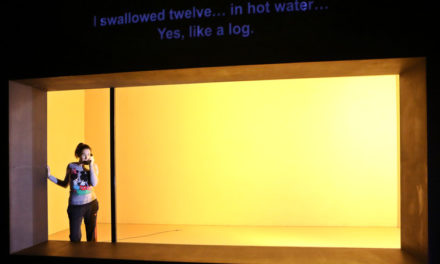

Tekoos El Esharat Wal Tahawolat. Photo: Bassam Al Zoghby

The limits of adaptation

Wahda Helwa (A Beautiful Woman) was directed by Akram Mostafa, and based on A Lonely Woman by Dario Fo and his wife Franca Rame. Mostafa successfully strayed from the details of the original work to create a very localized play, in Egyptian Arabic, about the condition of women in Egypt.

“Young artists often do not understand the limits of adaptation and playwriting, in my opinion. This is reflected in the plays shown at the festival, which constitute, in a way, a summary of this year in theatre,” explains Khamis, citing Islam Imam’s Otrok Anfi Min Fadlak (Let Go of my Nose, Please) as an example. The latter is a flagrant example of an artist who cannot differentiate between playwriting and literary adaptation.

Imam also claims to be the author of the play, when his work is based on two other, well-known works: Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, and Mexican author Maruxa Vilalta’s Question of Nose–a misappropriation which brought on much criticism last winter, when the play was first staged. Thus the festival has sparked much debate surrounding the question of adaptation.

Young people in line

There were often long lines in front of the venues hosting the National Theatre Festival. The plays performed by University troupes, in particular, attract a young audience, as was also the case in the past, as these fresh and original creations are highly appealing to the public.

Venues are fully booked an hour prior to the opening of the show. Tickets are usually free, but they have to be acquired in advance. When young people arrive late, there are no places left, resulting in general discontent, which was manifest on several occasions. Artists sometimes attempt to intervene and calm the audience; they usually end up promising a second showing.

Yet several of the student productions shown this year were not up to par, and rather fell into the trap of monotony. Among them was Pinocchio, a play staged by the faculty of literature at Helwan University.

While the staging and visuals were quite interesting, the sequences follow each other with no great purpose, and there was a real problem with the dramatic construction of the play. The student production strays far from the well-known children’s tale. Here, it is rather the story of a puppet struggling to blend into the world of the living, and suffering from this hopeless attempt.

Moghamrah Raas El-Mamlouk Gaber (The Adventure of the Head of Mamluk Gaber), staged by the faculty of literature at Cairo University, is an adaptation of Saadallah Wannous’ work.

The acting was banal and the literary adaptation was weak. The actors were trying to make the audience laugh, but all they did was repeat futile jokes. The back and forth between current events and the events of the story was in no way useful to the plotline. The applause from the young audience, most of whom came to support their friends, was not a testament to the greatness of this mediocre play.

The play Cinema 30 was the only exception. Written and staged by Mahmoud Gamal, who has been one of the stars of student theatre since 2013, the play was performed by the students of the faculty of commerce of Ain Shams University.

Gamal, who has written many a successful piece, including 1980 Wa Enta Talea (Generation 1980) and Al-Prouva (The Practice), has managed to impress audiences once again with a play in which everything is black and white, just like in 1930s Egyptian cinema. Yet superfluous details and repetition rendered it excessively long, harming the play overall.

With about one successful play out of every ten, and despite the presence of an audience coming to support their artist friends, the nature of this fascination with student theatre could be called into question.

This article was originally published on Ahram Online. Reposted with permission. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by May Sélim.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.