When, some eight or nine years ago, I began researching the responses of Australian and refugee theatre-makers, filmmakers and writers to asylum seeker debates it was very easy to share the hopes for political change that underpinned much of their work.

Theatre is a fundamentally ephemeral art, and one of my aims in editing the new collection, Staging Asylum: Contemporary Australian Plays about Refugees, was to account in some way for theatre’s unique role in heated and ongoing cultural conversations about how Australia treats asylum seekers.

Theatre movements that opposed the baldly punitive asylum seeker policies introduced by the Keating Labor government and fortified under Howard’s conservative coalition tended to coalesce around many of the same imperative verbs as activist organizations: Change! Stop! Free! Support!

There’s a habit we English speakers have of turning to French for neat epigrammatic flourishes: how apt, for instance, is that Gallic philosophical shrug, plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose (the more it changes, the more it’s the same thing), to the subject of refugees in this country?

What can political theatre do?

And while I’m sure plays about asylum seekers’ plights tend to generate discussion among those already sympathetic more often than they provoke conversions, they nevertheless push a discussion forward – crucially, within the public sphere, where critics who are for or against a play’s politics may enter the fray. Theatre is unique in this context because of its peculiar capacity to inspire subjective (personal) and intersubjective (collective) meaning-making.

Staging Asylum is, perhaps surprisingly, the first of its kind, and it complements academic work that has painstakingly archived plays that might otherwise have faded from memory.

The purpose of political arts is sometimes assumed to be broadly akin to that of activism – certainly, a politically-inflected theatre is frequently evaluated in terms of what it might do – even though few theatre practitioners would wholly subordinate the functions of imagining, communicating, questioning, reflecting and crafting to the aim of efficacy. Anyhow, the intention isn’t a zero-sum equation.

Doubts and limits

I’m sure that, in the last two or three years, a good many of us involved in Australian theatre, in whatever role, have had to recalibrate our beliefs in the cumulative capacity of theatre about refugees to trouble consciences and topple policies.

Obviously, this hasn’t happened.

The current global neoliberal consensus dovetails all too elegantly and adamantly into moral arguments for why political leaders of wealthy nations have an obligation to guard against errant and burdensome foreigners.

That some foreigners of the impoverished variety are both errant and burdensome is convenient; certainly this seems to be a far easier discursive pill to swallow than less digestible statistics on net benefits (and here the diet of Australians seems broadly similar to that in Britain, where the BBC has just screened a documentary on criminality and addiction among undocumented immigrants in Ilford, north-east London).

Even though refugees are owed protection from UN Convention signatory nations irrespective of their economic value, their presence is nevertheless weighed in popular discourse in terms of contribution versus a burden. Refugee advocates themselves frequently orient their arguments around this ledger, presenting myth-busting arguments for why refugees are not only economically “viable,” but also morally deserving.

Why these plays?

In selecting plays for Staging Asylum, I wasn’t interested in resurrecting the moral standing of asylum seekers and refugees – after all, a presumption of generalized “innocence” serves characters in plays far less well than it does the accused in our criminal justice system. I chose plays that staged the consequences of Australia’s dominant narratives on asylum in the lives of refugees and Australians.

What might surprise readers is the book’s preponderance of ironic and satiric work.

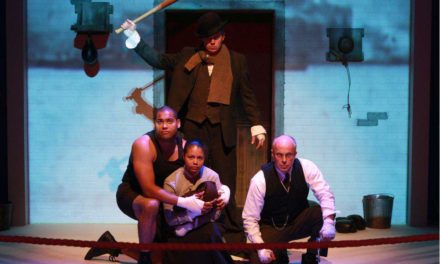

The first play, CMI (A Certain Maritime Incident), created by Sydney political theatre collective version 1.0 and performed in Sydney and Canberra in 2004, pushes verbatim theatre beyond naïve transparency to “remix” the 2002 Senate Select Committee on the Children Overboard incident and SIEV X disaster.

Two darkly funny plays by young playwrights, both of which premiered at Brisbane’s Metro Arts Theatre in 2006, Victoria Carless’s The Rainbow Dark and Ben Eltham’s The Pacific Solution, reimagine Australian suburban homes as sites of petty anxieties over the right to belong, and the power to exclude.

Linda Jaivin, something of an expert in the obscure genre of refugee satire, injects the odd wry exchange into an otherwise somber short play, Halal-el-Mashakel, inspired by young detainees she got to know as a visitor to Villawood IDC. Jaivin’s play was performed in Sydney, Canberra, Wollongong, Newcastle and Adelaide in 2003 and 2004.

Two plays in Staging Asylum were written by refugees.

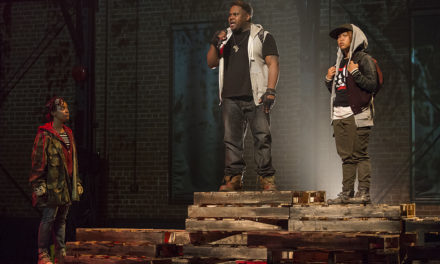

The collaborative community production, Journey of Asylum – Waiting, devised by members of the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre in Melbourne in 2010 and directed by Catherine Simmonds, presents a series of vignettes based upon members’ experiences before, during and after their arrival in Australia.

Towfiq Al-Qady’s Nothing But Nothing, performed by the writer at Brisbane’s Metro Arts Theatre in 2005, is a solo, stream-of-consciousness narrative that distils Al-Qady’s experiences and those of other Iraqi refugees.

It was Al-Qady’s play that pushed me most insistently to question my investment in the argument that tropes of refugee victimhood reinforce political powerlessness and risk voyeurism. Al-Qady’s text, with its direct (and yes, earnest) account of victimization and suffering, reminded me that when it comes to certain stories about one’s own life, any register other than distress may be a luxury.

That the relationship between theatre and political change is neither direct nor inevitable doesn’t mean people are going to stop making politically motivated work.

The six plays in Staging Asylum register the fact that the precipitous erosion of asylum seekers’ rights in the post-Tampa era has not gone unremarked in Australian theatre.![]()

Emma Cox, Lecturer in Drama and Theatre, Royal Holloway

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Reposted with permission. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Emma Cox.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.