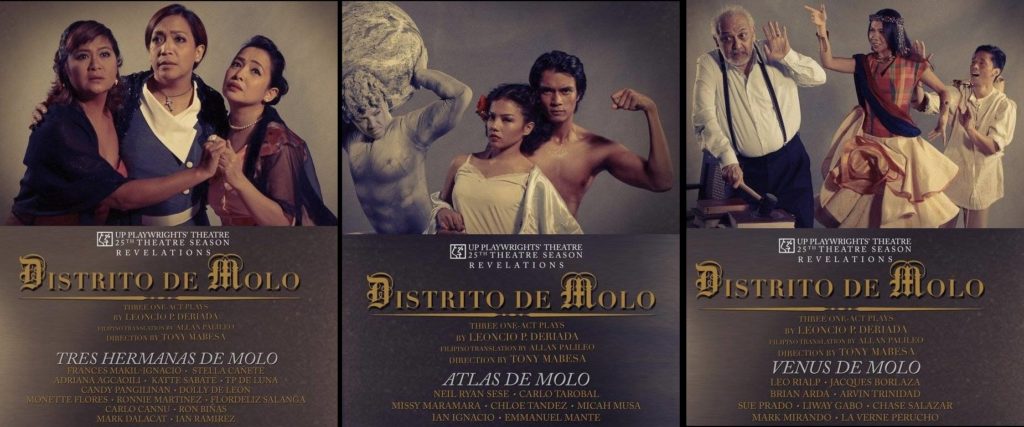

Quite possibly, for the inveterate theater-goer, what immediately comes to mind as one sits down to watch the official theater group of the University of the Philippines Diliman, Dulaang UP’s recent production—a triptych of one-act plays by UP Visayas Professor Emeritus and Palanca Hall of Fame awardee Leoncio Deriada, directed for the stage by Tony Mabesa—is Nick Joaquin’s A Portrait of the Artist as Filipino.

Like Nick Joaquin’s magnum opus, the plays in Deriada’s Distrito de Molo are theatrical odes—or more properly, dirges—for a grandiose city (and a life) that has long since capitulated to the ravages of historical time. In particular, these plays are about the legendary Molo district of Iloilo City, home to many illustrious and wealthy Ilonggo clans, whose majestic ancestral mansions still dot the much-revised landscape, albeit in increasingly sorry and decrepit states.

As in the famous lament for the loss of the distinguished and ever-loyal Intramuros, a crucial temporal marker for this trilogy of plays is the Second World War, an entirely catastrophic albeit little-discussed passage that has irreparably transformed—and, in many ways, destroyed—the character of this formerly urbane and cosmopolitan corner of Panay island, as well as the lives of its once-gracious residents.

Teresa Paula de Luna and Stella Cañete in the first play of the trilogy, Tres Hermanas de Molo. Photo credit VladGonzales.net

Central to these plays is art-making, both as a metaphor and as a literal activity, and even this recalls the crucial role played by Don Lorenzo Marasigan’s “classically themed” painting in Joaquin’s famous dramatic allegory. In all the three plays of Distrito, specific pieces of (likewise, mostly “classical”) sculpture function as symbols for personal and collective memory, as well as the material culture that it both engenders and is engendered by.

In the first play, Tres Hermanas de Molo, the three spinster sisters Visitacion, Asuncion, and Salvacion—arguably a throwback to the comparably tragicomic Paula and Candida—must decide to set themselves free from the specters of their traumatic pasts, whose claim to their present-day lives is their spooky and much-storied ancestral house and all the affinities and devotions that it embodies.

The commissioned sculpture of a downcast demon—caught under the heel of the winged prince of the heavenly host—haunts this play, like the secret loves and transgressions that the three sisters have kept from each other, but whose unbosoming surprisingly provides a common ground of compassion for them all. The play’s moving epiphany reawakens the sisters’ familial affection, as well as their loyalty to their mutual origins and hurts, that they must at once embrace and forgive, if only to go on living in the difficult but still possible present.

The second and third plays pursue the “Pygmalionesque” motif, but take it to darkly humorous and mythically resonant places that the original referent couldn’t have remotely anticipated. In Atlas de Molo, we are presented with the character of Eric Avanceña, the contemporary and superficial scion of a genteel and eminently continentally educated ancestor, one of Molo’s legendary founding fathers. Because his obsession with his own physical pulchritude is far from Neoplatonic (and is, therefore, merely Philistine), Eric becomes the beneficiary of a visitation by the supernaturally animated and classically argumentative statue of Atlas, left forlorn in the once-verdant and luxuriant garden, and thus literally a vestige of Molo’s glorious and Europeanized past.

Eric suffers from materialism and unremitting self-love—a pomposity that proves to be his own vainglorious undoing, when the statue lures him into taking its place in the middle of the dilapidated fountain. There, impaled on his vaunted pedestal, the culturally faithless and egotistical man promptly freezes into stone, even as his lookalike now takes over his life, which will henceforth be more metaphysically grounded, reinvigorated, and substantial—as well as happy, with the wife being entirely oblivious to the bizarre body-switching, all too pleased as she finally is to have a less narcissistic, more loving, and eager-to-please husband by her side.

It’s in the third play, Venus de Molo, where the difference with Joaquin’s familiar vision comes starkest, for it depicts its world as being helplessly transitional and simultaneous—its cognitive and cultural dissonances being all too clear in the chasmic divide between Iloilo’s landed and Westernized elite on one hand, and on the other the peasant, mountain-dwelling, and folk, who are also the keepers of this mythologically rife island’s enduring pre-Conquista memory. By contrast, Joaquin’s peace- and war-time Intramuros appears thoroughly Westernized, its spiritual systems converted effectively away from the animist toward the Catholic—in particular, the Mariological (of course, while this seems to be the case in A Portrait, it isn’t entirely true of Joaquin’s oeuvre, as a whole: in his novels and stories, we, in fact, see Joaquin eloquently arguing for the persistence of autochthonous energies well into colonial and neocolonial times).

In Deriada’s third play, we see this mythological conflict coming to a veritable head, when the Hispanic Don Guillermo Arroyo commissions an indigent native sculptor—a descendant of Panay’s famous babaylan, Estrella Bangotbanwa, viciously demonized by the island’s ecclesiastical authorities—to make for him a replica of Venus de Milo. Soon enough this agonistic world’s repressed indigenous energies conjoin with the pent up resentments of its downtrodden and dispossessed, and their potent brew—a disavowed but powerful class antagonism between Ilonggo society’s teeming taga-uma and its buenas familias, that in fact seethes everywhere in this trilogy—bubbles up to this play’s mythically luminous surface.

Memorable enough, the trilogy ends phantasmagorically, with the apparition of the primordial animist goddess Laun Sina who, identifying herself with all the disgruntled deities that the monotheistic tyranny has exiled throughout history, proceeds to call down her punishment—classical locura, or madness—on the greedy and uncharitable landlord and his fetish for all things nostalgically colonial, derivative, and fake.

Hence, despite its comparable investment in the mythologizing of communal place, what distinguishes this play is its recognition of cultural continuity despite the traumas of historical rupture—something possible to imagine for this unevenly developed and ex-centric part of our country perhaps, but ostensibly not for Manila, its social and economic center, which has borne the privilege (and the brunt) of both national and global incorporations across the brutally syncretic centuries. This constitutes a vision of “hopeful recuperation” that Joaquin’s play—enmeshed as it is in the utter devastation of wave after wave of violent and merciless conquest— sadly can no longer entertain.

Mabesa’s direction is pretty straightforward, although he does give himself over to fitful moments of whimsy, as well—especially since the plays do encourage it, in between whiles. Originally anglophone texts—written by one of our country’s best and most accomplished writers in English—what’s pleasantly surprising is that these plays do lend themselves relatively seamlessly to the rituals of interlingual translation, as Allan Palileo’s carefully textured achievement so audibly proves. Nick Deocampo’s stage design looks and feels appropriately cinematic, while the performances of the Filipino cast are all exceptional, as well—especially those by the formidable Frances Makil Ignacio and Adriana Agcaoili, the ethereally and maternally androgynous Ronnie Martinez, Missy Maramara, Sue Prado, and the always dependable and charming Neil Ryan Sese.

The English and Filipino versions of this trilogy of plays had a successful run for three weeks at the Wilfrido Ma. Guerrero Theater of UP Diliman in October 2016. A restaging is scheduled in February 2017 at the University of the Philippines in the Visayas (Iloilo City). Original Philippine Theater at its finest. Go and watch.

J Neil Garcia is a professor of creative writing and comparative literature at the Department of English and Comparative Literature at the University of the Philippines Diliman.

This essay published online via GMA News Online on 2 November 2016. Reposted with permission. To read original essay, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by J Neil Garcia.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.