Lorca’s first play contains beautiful verses. However, its characters, a group of insects did not conquer the audience’s fervor, but received instead boos and jeers. In their version of Lorca’s incomplete text, Trece Gatos include songs and their own identity.

| El hilo va a la estrella

donde está mi tesoro. Mis alas son de plata, mi corazón es de oro. El hilo está soñando con su vibrar sonoro. |

Thread reaching to a far-off star Where all my being’s to be found. My silver wings, my heart of gold, Thread dreaming of the magic sound.[i] |

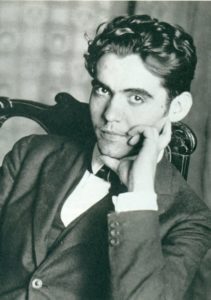

Federico García Lorca (1898-1936) premiered his first theatre play, El maleficio de la mariposa (The Butterfly’s Evil Spell) in 1920 at the Eslava theatre in Madrid. It only ran for four nights, and it received a “beautiful booing,” according to Lorca.

The audience at the Eslava was however used to avant-garde productions, and García Lorca had brought a good claque from the Residencia de Estudiantes. To no avail, it was not enough to avoid the play’s resounding disaster. They still did not know him who will become one of the most important poets in Spanish of the 20th Century, or even the most important one.

The Butterfly’s Evil Spell premiere in 1920. La Argentinita as the Butterfly, center. Courtesy of Moon Magazine.

The Butterfly’s Evil Spell shows some features of Lorca’s later theatre, but the staging is determined by the space in which the tragedy takes place: a field amplified by a powerful magnifying glass, with cockroaches[ii], worms, a butterfly and a scorpion. All these insects are the characters in the play, which has a certain Franciscan praise of the insignificant natural world. It is not the only one, as Lorca gave voice to beasts in other plays that were never staged and for which we only have fragments. One of them is Of Love (Animal Theatre) (1918), a one-act play with a dove and a pig as main characters, accompanied by a choir of cicadas, a donkey and a nightingale.[iii]

In the Residencia de Estudiantes, Lorca became interested in Ultraism and Surrealism, he met important theatre figures of the time, and he took part in avant-garde movements. In this context, giving voice to insects, dressing them with human passions or imagining them as if they were little people did not seem risky. However, the audience’s rejection of the roaches outweighed the aesthetic appreciation of the play. Revulsion prevailed and the insects did not receive their deserved recognition on stage.

The genesis of the play was humble. Lorca met Gregorio Martínez Sierra, director of the Eslava theatre, at the Centro Artístico y Literario in Granada. Lorca recited a poem for him and Catalina Bárcena —Martínez Sierra’s first wife and first actress in the Eslava company-, a poem about a butterfly with a broken wing that falls into a nest of roaches. The roaches take care of her and cure her wing. When the butterfly flies away, she leaves behind a small cockroach who dies love-struck.

Ian Gibson — who was not there, but heard the story — documented Martínez Sierra’s reaction to Lorca’s poem:

This poem is pure theatre! Marvelous! You must extend it and turn it into real theatre. I give you my word that it will open at the Eslava.[iv]

Federico García Lorca, around 1925. Courtesy of Moon Magazine.

When Federico finished reciting the poem, – Gibson explains – Catalina Bárcena’s face was covered in tears and Martínez Sierra could not contain his enthusiasm.

The young Lorca –as often happened- had enraptured his audience. Lorca agreed with pleasure, excited to premiere a play in the most avant-garde theatre in the capital. The play was first titled Comedia ínfima (Minimal Comedy), then La estrella del prado (The Meadow’s Star) and finally, following Martínez Sierra’s suggestion, it was entitled El maleficio de la mariposa (The Butterfly’s Evil Spell).[v]

It premiered on March 22nd, 1920. With music by Grieg, cubist set designs by Mignoni, and costume design by Barradas. Encarnación López, la Argentinita, played the wounded Butterfly, and Catalina Bárcena played the young cockroach (the Boybeetle).

The text in verse is, according to Lorca, a sin of youth. Years later, in an interview with Juan Alfarache for the only issue the ambitious magazine Miradero, edited by José Gallo Renovales, García Lorca would declare his reluctance to use verse for drama: “prose gradually makes us become owners of ourselves as the years go by.”[vi]

Besides the avant-garde features and the love for puppet theatre, The Butterfly’s Evil Spell also includes modernist elements characteristic of Lorca’s early phase: synesthesia, musical lexical choices, precious stage directions, care for every little detail. However, as the genuine supporter of the avant-garde he was, Lorca did not limit himself to the modernist canon, but he rather subverted it: not all the insects in The Butterfly’s Evil Spell are beautiful. The caterpillar contains the germ of beauty, since it will transform into a butterfly. The scorpion incarnates evil and represents danger, so it is ugly, like in children’s fairy tales. The butterfly is all beauty. Beauty and death. And the cockroach… Oh the cockroach!

Lorca dignifies the humble cockroach; far from despising this modest and disowned animal, he does not emphasize its ugliness. When the Boybeetle (the young male cockroach) falls in love with the Buttlerfly, Lorca reproduces the relationship of Beast and Beauty with no Beast: he makes both of them beautiful. There is no Beast, no ugliness in the Boybeetle. The first audience and critics did not understand it and thought choosing cockroaches as protagonists of the play was grotesque and unnecessarily ugly. This is Andrenio (Eduardo Gómez Baquero)’s main critique in his review, published in La Época: Lorca’s main mistake was presenting a drama with beetles since these will never be a “poetic symbol”[vii]. Manuel Machado’s rejection of the play is more subtle. Even though he does not think a story of cockroaches can possibly have a dramatic development, he saves Lorca’s “beautiful verses.” He rejects the cockroach for being too simple, not too ugly, but he praises Lorca’s poetry. Manuel Machado anticipates Lorca’s future trajectory as a poet.

The Butterfly’s Evil Spell is in fact much more than it seems. We might not be before the best Lorca yet, but some of Lorca’s poetic language is present, and some of the motifs that will inhabit his later theatre: unrequited erotic passion, impossible love, death… These passions incarnated not by a young woman, her young lover, a father…, but by a group of insects. Lorca vindicates the ugly, the humble, the marginalized and reproves men “full of sins and incurable vices.”

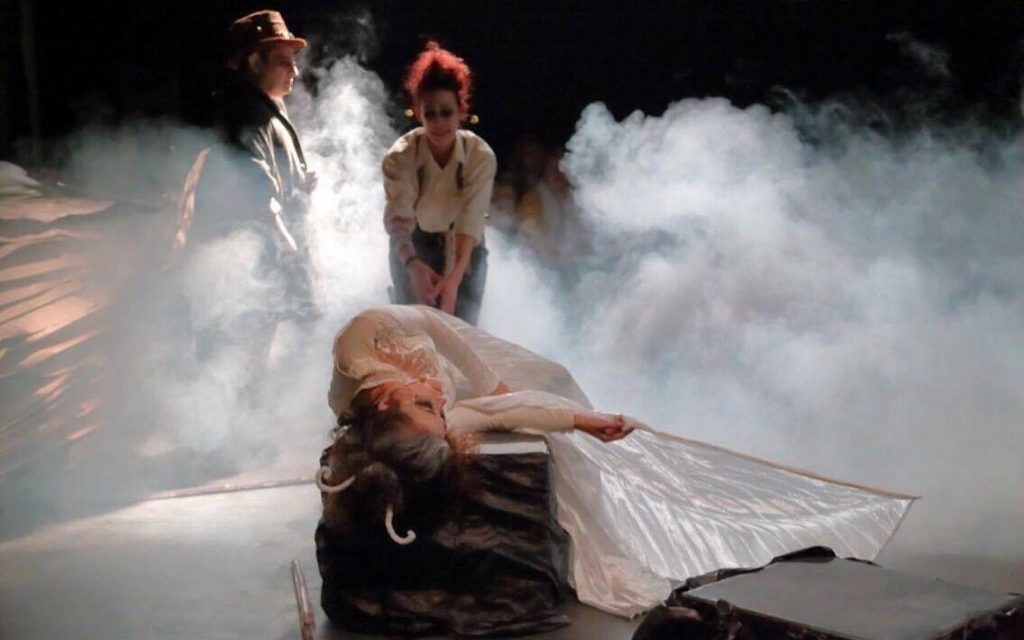

Carlos Manzanares and Trece Gatos’s new version of The Butterfly’s Evil Spell.

Isn’t this impossible theatre the most suitable for Trece Gatos to populate the stage of the “Sala del Mariano” with poets, insects and lovers?

We don’t have the full text of The Butterfly’s Evil Spell. The ending is missing in all the existing manuscripts. Carlos Manzanares has finished the play and added songs and music, and Trece Gatos has produced The Butterfly’s Evil Spell at the Sala del Mariano, in Madrid.

Trece Gatos respects the light spirit of The Butterfly’s Evil Spell. The tragedy is minimal, as are its protagonists. They keep the rhythm and musicality of the verse away from grandiloquence. The actors are not trying to stand out, shake, or shock the audience. The performances of the thirteen actors and actresses, especially the actresses, are extraordinarily natural, even in such a bizarre dramatic context.

The newly added songs highlight the emotions of the characters. Carlos Manzanares’s music has a certain emotional blackmailing that one accepts willingly. It constantly appeals to our senses: synesthesia, total darkness that announces the drama, its touch, its small steps… a darkness full of sounds that awakens us and predisposes us to contemplate beauty.

True to their post-punk aesthetics, Trece Gatos has the characters wear sinister makeup and postindustrial costumes. Trece Gatos uses an extensive scenic space, adding part of the orchestra (by removing some of the seats) to the stage. The audience sits in a U shape around the performing space: a forest in two levels. Thirteen actors on stage, a small meadow amplified for this little tragedy. Little not for presenting small passions, as we said, but for the humble, insignificant origin of its protagonists: cockroaches, caterpillars, a scorpion and a butterfly.

Raquel León and José María Mora in Lorca’s The Butterfly’s Evil Spell, by Trece Gatos. Courtesy of Moon Magazine.

Another innovative element: Carlos Manzanares uses the prologue and Lorca’s stage directions as another character –which they are. Lorca mentions a sylph on crutches “who had escaped from a play by the great Shakespeare.” Like a demiurge, this sylph appears next to a miniature reproduction of the scene. Cosmos and microcosms reproduced again. Next to the little world inside the little world, the sylph pronounces the prologue and the stage directions like it were his text. Carlos Manzanares recuperates for the stage these beautiful and original Lorquian fragments that were conceived – like in Valle Inclán’s theatre- as a sophisticated way to give stage directions.

The final product is a delicious show for children and adults alike who are willing to be enraptured by the sylph’s words.

The Butterfly’s Evil Spell

Author: Federico García Lorca

Director and text adaptation: Carlos Manzanares Moure

Cast: Himar Armas, Teresa Bailón, Ana Blanco, Vanessa Bou, María Díaz, Celia Ferrer, Estefanía Hernández, Ángeles Laguna, Raquel León, Paloma Maestre, José Mora, Elena Sanz, Carlos Manzanares Moure

Music: Carlos Manzanares Moure

Producer: Trece Gatos

This article was originally published in Spanish in Moon Magazine. This reduced translation is republished with permission of the author. Read the original (longer) version in Spanish here. Translated from Spanish by Mara Valdemarra

[i] N.T. Translation of fragments of Lorca’s The Butterfly’s Evil Spell by Gwyne Edwards. Lorca. Plays: Two. London: Methuen, 1990.

[ii] N.T. In Lorca’s version the insects are roaches, but in English translations they are often beetles.

[iii] Cf. Juan Antonio Rodríguez Pagán, El otro lado de El Público de Lorca, Isla Negra Editores, San Juan, República Dominicana, 1999, p. 34.

[iv] Ian Gibson’s work is based on testimony by José Mora Guarido and Miguel Cerón. Cf. Ian Gibson, «En torno al primer estreno de Lorca (El maleficio de la mariposa), in Ricardo Domènech (edit.), La casa de Bernarda Alba y el teatro de García Lorca, Madrid, Cátedra, 1985, p. 63.

[v] Cf. Juan Antonio Rodríguez Pagán, El otro lado de El Público de Lorca, Isla Negra Editores, San Juan, República Dominicana, 1999, p. 42.

[vi] Cf. Liz Perales, «Lorca: mi primer estreno fue un hermoso pateo», El Cultural, February, 23, 2012.

[vii] Quoted by Manuel Fernández Nieto, «El maleficio de la mariposa en el teatro de su tiempo», Estudios ofrecidos al profesor José Jesús de Bustos Tovar, vol. 2, edited by José Luis Girón Alconchel, F. Javier Herrero Ruiz de Loizaga, Silvia Iglesias Recuero and Antonio Narbona Jiménez, Facultad de Filología de la U.C.M., Instituto de Estudios Almerienses, Madrid, 2002, pp. 1361-62.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Alfonso Vázquez.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.