Almighty Voice and his Wife, a play written by Daniel David Moses in 1991, was recently staged in Toronto. It is the first Indigenous play on the stage of Soulpepper Theatre, Toronto’s largest not-for-profit theatre. This production was directed by Jani Lauzon who performed in the female lead role in the original Ottawa production.

The play with an Indigenous-led creative team asks the settler audience members to reflect on their position in history, their gaze, and their internalized racism. It reimages a 19thcentury story about an Indigenous man named Almighty Voice and his wife whose name is not mentioned in the official documents. Taking dialogues from the official transcripts of Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Moses reconstructs an alternative history. The play has two acts and the two acts of the play stand apart, as though they could be from two different plays. The first act is a story of an Indigenous couple, Almighty Voice and White Girl, trying to survive against a series of acts of colonial violence. In the second act, Almighty Voice is a ghost and White Girl is a cruel white interlocutor who hurls racist abuses at Almighty Voice, often alluding to various historical incidents of settler-colonial brutality on Turtle Island or what settlers call North America. The link between these two acts is not explicitly shown until the end except through a few hints.

The first act unfolds a tragic love story of a young Cree couple. We see glimpses of the effects of psychological violence on White Girl as a child in residential school. White Girl’s fear of “white god,” about whom she learned in residential school, makes her not want to use her Indigenous name. She is afraid that the colonizer’s God will harm her and her husband if they use their Indigenous names. The play indicates how colonialism implanted self-hatred, fear, and it forced Indigenous people to “voluntarily” lose their identity. After her husband, Almighty Voice kills a government cow for their wedding they have to be on the run, trying to escape from the colonial officers. In his efforts to not get caught and sent to jail, Almighty Voice kills a Mountie in combat. He is shot dead by a colonial officer at the end of the first act.

One might expect to see the mourning of White Girl or the hardships of her and her children’s lives in the second act. However, the play does not give the audience the satisfaction of a catharsis, an emotional outpouring. Instead, the play turns its gaze to its audience now. In the first act, the beautiful set (designed by Ken Mackenzie) with a cloth or animal skin stretched over sticks with glimpses of the night sky at the apex. The poetic scene of the first act is replaced by the gaudy strings of colorful papers in the second act, which is a Vaudeville show, a theatrical genre of farce. Almighty Voice and His Wife plays with the history of the Vaudeville show which was degrading Indigenous peoples and their culture, but, simultaneously, it was the only place where Indigenous people were allowed to practice their art and culture. The actors address the audience directly as if we are the audience of the Vaudeville show of the past. There are jokes that are explicitly racist and colonialist. We, the audience, become the audience of the Vaudeville show who enjoyed and found humor in horrendous racism against Indigenous peoples. The play holds a mirror to the audience by enabling them to ask many questions- when do we (settler audience) laugh? What do we still find funny? When and why do we feel attacked? What is the connection between the audience of those Vaudeville shows and us, the audience of Almighty Voice and his Wife? The feeling of confusion and the disconnect that the audience feels, especially because it does not seem to be explicitly connected to the first act, at the beginning of the second act enables the audience to question their way of witnessing Indigenous history and art.

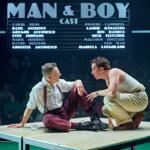

James Dallas Smith and Michaela Washburn. Photo by Dahlia Katz.

In a moving moment, White Girl, who returns in whiteface and a Mountie uniform, playing the role of the interlocutor, breaks down during a song. Tears flow and the white paint on her cheeks comes off. This is one of the few moments that connect the first and second acts. Michaela Washburn, the actress, brilliantly moves between the character of Interlocutor and White Girl. The stunning actress captures the complexity of having been forced to inculcate racist presumption about oneself by colonial institutions such as residential schools. James Dallas Smith does a wonderful job of playing Almighty Voice.

On the website of Soulpepper and in the program of the play, the description of the play starts with this line: “Romeo and Juliet. Orpheus and Eurydice. Almighty Voice and His Wife.” However, the play shows exactly how Almighty Voice and his wife are different from Romeo and Juliet or Orpheus and Eurydice. The play is a powerful unfolding of the relationship between love and coloniality. Here, the villain of the love story is colonialism and yet love is the source of resilience and resistance against colonialism. The love between Almighty Voice and White Girl helps them to find each other even after death. In their journey of finding each other, peeling off the disguise and the façade that colonialism imposed on them, they also make the audience come out of the comfort zone or privilege of spectatorship. This journey of love enables the audience to join in breaking the safe distance of watching the show as a disembodied subject without history. The play asks the audience to truly witness themselves by taking into account their position in this history.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Sheetala Bhat.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.