Acclaimed playwright Dominique Morisseau makes an auspicious Lincoln Center debut with her new play, Pipeline. Morisseau’s best-known work to date is titled The Detroit Project (A 3-Play Cycle), which includes the Obie Award-winning Skeleton Crew and Detroit ’67, which was produced at New York’s Public Theater.

Pipeline is a topical, searing examination of teenage angst, African-American anger, and generalized male rage. Set against the socially stratified world of private secondary education, Pipeline details the tragic struggle of a parent whose desire to cultivate greater opportunities for her child is thwarted by a curse-like force she cannot stop.

Quietly percolating hip hop music greets the audience upon arrival at the theater, setting the tone for a gritty evening of the soul. The immersive basement space that is Lincoln Center’s Mitzi E. Newhouse Theater features a white brick wall, a gray teacher’s desk center stage and little else. The stark scenic design by Matt Saunders also sports rolled on bedroom and living room furniture, used to artfully minimal effect. Hannah Wasileski’s black and white video projections of students in increasingly violent interactions are employed with such impact, it’s as if they were a supporting cast.

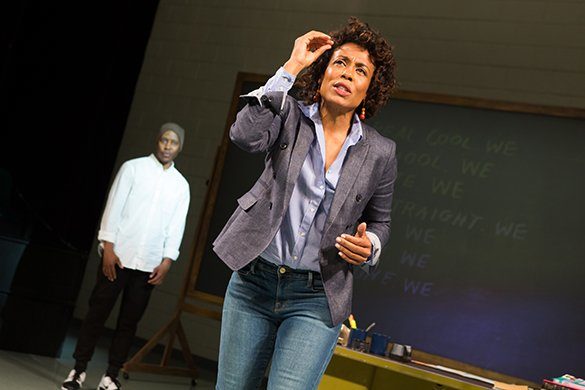

Like a classic Greek drama, the main action of the plot occurs offstage. Omari, played with gusto by Namir Smallwood, is a student at an elite private school where he has had an altercation with a teacher. Karen Pittman is a force of nature as his beleaguered mom Nya. She is the emotional centerpiece of the play. Pittman has both a tremendous role and an immense responsibility to shepherd the play from her opening scene to her monologue finale. Nya is easily one of the most expansive African-American women to grace a US stage. Pittman is happily up to the demands of the role.

Morisseau generously pays homage to poet Gwendolyn Brooks in an imaginative bit of staging which features Omari in a knit cap, reciting her poem “We Real Cool,” visible only to Nya. That touch of surrealism helps give the production an added dimension which further lifts it beyond more realistic portrayals of adolescent strife such as the US TV series “American Crime”.

Morocco Omari is a standout as Omari’s estranged father and Nya’s ex-husband Xavier. He is imposing in both voice and stature, and his bottled frustration is arresting to witness. Jaime Lincoln Smith likewise shines in a supporting role as a security guard at the school where Nya teaches. Their brief romance, we later learn, was the catalyst for the demise of her marriage. Smith’s understated charm and good looks make Nya’s attraction to him a seeming inevitability. Like the most accomplished supporting actors, Smith leaves you yearning for more.

The powerful Tasha Lawrence plays Laurie, a colleague and fellow teacher at Nya’s school. Lawrence resembles Oscar winner Marcia Gay Harden but with a more evident sense of humor. A bold presence, her character is most effective as welcome comic relief. When an incident with parallels to Omari’s is thrust on her, it seems to test her good humor more than might best serve the play.

Heather Velazquez rounds out the cast as Omari’s girlfriend Jasmine. Her depiction of an unsophisticated young woman is on point. Her urban lingo and mannerisms, while accurate, risk veering towards stereotype. A more nuanced portrayal would more clearly underscore not only why she’s so important to Omari but to the play itself. Her scene with Nya helps to reveal greater dimension to her role.

Director Lileana Blain-Cruz has a gift for eliciting strong performances with wonderfully delineated arcs from her powerful cast. She manages to underscore the innate poetry of the writing with a combination of pacing and imagery. The play shines brightest as an artful depiction of the current face of race and class conflict in the contemporary US.

Pipeline is at the Mitzi E. Newhouse Theater, 10 Lincoln Center Plaza in New York City.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Jack Wernick.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.