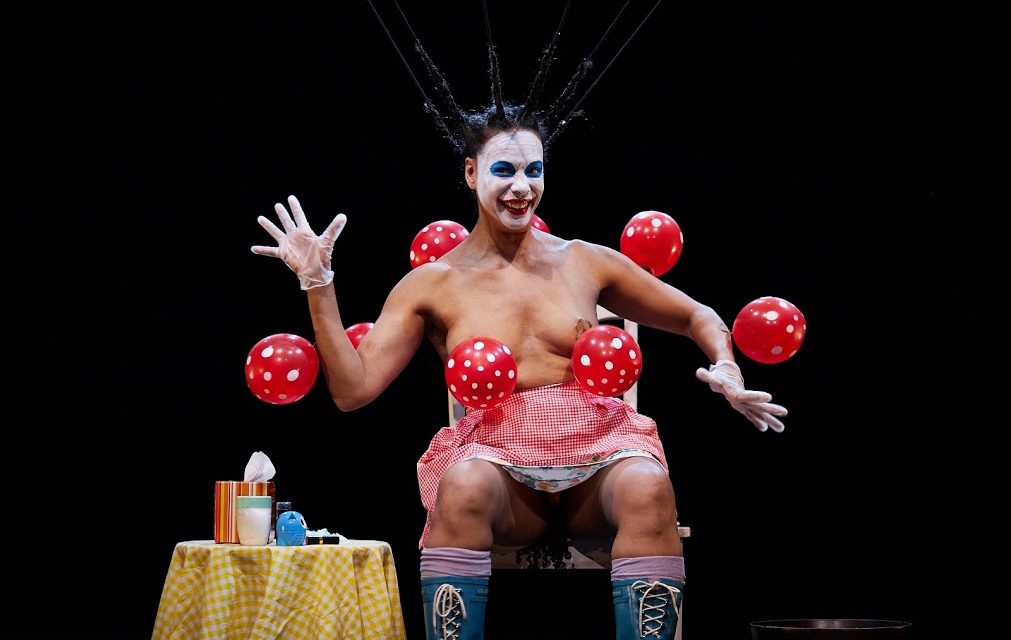

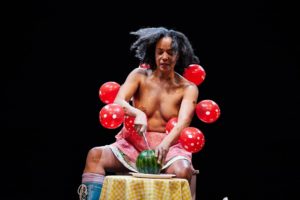

When I entered the theater at Mabou Mines for Edisa Weeks’ performance of Three Rites: Liberty, my first thought was: “That’s the most far out thing I’ve ever seen in my life.” Weeks was sitting on a chair in the center of the stage, topless with half-aprons tied around her waist and red balloons taped to her nipples and along her shoulders and arms. Her hair had been worked into six distinct locks, each of which was tied to a string, suspended through a rope and balanced at the other end by a weighty object – a red bible, a black dildo, a blonde wig, a gun, a lightbulb, a small watermelon. Her face was caked with white and painted bright blue around the eyes, like a child’s drawing of a face. (Later on, she would repaint her face tar-black with white around the eyes, turning herself into a golliwog.) As the audience members streamed in, Week’s limbs bubbled with energy, as if a motor were whirring at all points just beneath her skin. The whole scene was at once familiar and profoundly defamiliarized.

When the performance began in earnest, her facial expressions and movements conveyed invitation, fear, anger, surprise, love, and sheer delight. Weeks communicated all this without speaking a word, and the audience responded: laughing, mimicking her gestures. At one point, she made parched-throat noises, and two men got up to pour her water from an on-stage cooler. We were in her thrall.

The second part of the performance was more sober: looking straight at the audience, Weeks calmly removed the makeup from her face as a pre-recorded lecture was piped in: “The Pathologizing of the African American by Psychiatry” by Gary Null. The lecture traced the American medical community’s various “scientific” explanations for the supposed intellectual inferiority of Black people, a series of justifications for dehumanizing oppression from slavery through eugenics to today’s mass incarceration. The text was powerful and made a convincing historical argument, yet Weeks’ use of it is puzzling. Gary Null is not a researcher or doctor but a talk show host; he’s courted controversy by attacking the science of vaccination and even the link between HIV and AIDS. The lecture quoted in Week’s performance struck me as persuasive, so maybe it’s Null’s broken clock moment. Then again, maybe this is an intentional gesture of embrace and forgiveness. In an age of constant cultural cancellations, Weeks’ inclusion of a problematic voice in her fight against racist oppression. The fact that Weeks speaks only in the third act gives more weight to each word, so I remember her conviction when she said, “I don’t need allies. I need accomplices.”

In fact, a lot of this performance made me feel embraced. I’m rarely moved to tears by the sight of someone eating watermelon (Rarely but not never. See Chekhov’s short story “The Lady with the Lapdog.”). Weeks told the story of her great-great-grandmother the talented melon farmer, and the historical origins of the racist stereotype that to this day makes watermelon a thing to be consumed by Black Americans only in private, if at all. Then, as she enumerated the fruit’s health benefits, she sliced one up and passed it around with napkins, as her mother taught her was proper. The sweet smell perfumed the theater as everyone happily tucked into a slice, and this communal act drove home the undeniable yet ridiculous power of stereotyping.

Three Rites: Liberty. Photo by Tucker Mitchell.

To the feigned shock of the media, blackface in the news again this week. Three Rites: Liberty represents an explanation, and an exorcism, of that and other age-old symbols of oppression. Yet what I saw was only one component of Liberty, which is a huge installation of sculpture, word-art, and movement. And Liberty is only one component of Three Rites; the other two, as our Founding Fathers would have it, are Life and Happiness. It’s all the work of DELIRIOUS Dances, Weeks’ innovative and ambitious theater-dance company. What I saw was confrontational, visually and textually, and it challenged, or rather inspired me to reexamine some of my own ideas and behaviors. It was also funny, exciting and inventive. It was also sweet, refreshing and restorative, like a watermelon, free at last to just be a watermelon.

Three Rites: Liberty, a practically perfect work of political theater, is an almost impossible act to follow, and I have to give props to Cristina Pitter, for stepping into that space with her solo show decolonizing my vagina. The two works share some concerns: the exaggerated sexualization of Black people, the effects of internalized racism. But where Weeks’ show is wildly imaginative and visually impactful, Pitter turns inward to explore the terrain of her own mental landscape. Weeks dared to bare herself physically; Pitter did it with words.

decolonizing my vagina. Photo by Tucker Mitchell.

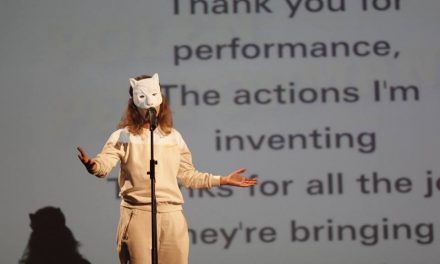

Pitter self-identifies as a “queer fat babe interdisciplinary artist, sex educator, activist” and more. In her show, she sings, recites poetry, and performs rituals of cleansing and confrontation. It’s a fundamentally intersectional exploration her sexual and romantic experiences, a reckoning with desire, shame, vulnerability, and courage. As a performer and, and especially a poet, she’s a powerhouse. But the format of the show revealed the limits of theater that is purely personal: in the absence of dramatization, the only material on the stage is the performer’s own feelings. As a spoken word, it’s a home-run. But as theater, it leaves something to be desired.

A one-person show requires a sort of unavoidable solidity. The solitary performer has to provide enough tension, surprise, resolution, to make it compelling, to make us care. I care deeply about the issues Pitter set out to explore – the racial biases in sex and dating that go largely unexplored, the basically humiliating experience of female heterosexuality. But Pitter failed to transcend cliched representations of attraction and rejection, and never brought me to new ideas of anything other than her own romantic misadventures. That’s certainly enough for good story-telling, but with a provocative and fundamentally political title like decolonizing my vagina, I expected more freshness, inquiry, and integrity than, for example, a devil-may-care delivery of lines like, “You have a fiancée? Kiss me anyway!”

decolonizing my vagina. Photo by Tucker Mitchell.

The best part of the performance was a simple and honest ending. After realizing that she is “allowed to ask for help,” Pitter took up a stack of notebook paper, came into the audience, and began declaiming her own poetry. She would single out an audience member, read the poem directly to them, and then give them the paper to keep. Earlier over-stylized vocal patterns gave way to a soft directness. Here, Pitter was at ease, but also truly vulnerable. No distance separated her from the audience. No mannered movements gave the impression of being tough, strong and unapologetically horny. It wasn’t particularly dramatic, but it was honest.

In the end, Pitter knows exactly who she is as a poet, performer, and person (I’m sure she slays when she puts on her sex educator hat.) If she ever wants to move more in the direction of abstract political theater, she need look no further than Edisa Weeks and DELIRIOUS Dances. For now, I’m glad they’re both out there making theater-art that’s expressive, illuminating and moving. Weeks ends her show with a call-and-response chant: “I will, we will end racism. I will, we will, end oppression.” Here’s my response: I will, we will, support artists doing the same.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Abigail Weil.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.