A successful play is a machine all of whose parts are thoughtfully selected to serve its overall logic. Among different drama forms, the machine of the monologue is especially complicated and seems to need more forethought and calculation to work properly and to avoid the possible pitfalls awaiting this genre. One such pitfall is monotonousness and ennui. Barefoot, Naked, Heart in His Hand with the Burnt Caravan, which was staged at The Divār-e-Chaharom Venue in Tehran, Iran, in February 2019, overcomes this drawback and manages to maintain its attraction and the audience’s fascination to the end. Thanks to its well-structured script, professional directing, powerful acting, smart set, and mise-en-scène, and the wise use of music, the play becomes a success.

The plot of the play, written and directed by Alireza Kooshk Jalali, Iranian playwright, and director, is based on a tragic incident that happened in Germany in 1993. A group of young neo-Nazi men set the apartment of a Turkish immigrant family on fire. In the fire, five members of the family perished, and the father and a little son survived. To turn this catastrophe into a play, instead of writing a drama full of pity and tears, Jalali chooses the framework of tragicomedy. This form, by simultaneously possessing a tragic and a comic quality, grants a dynamic rhythm to the monologue, which, alongside the alienation effect, makes the audience experience the bitterness and ugliness of the misfortune with an alert mind.

The play is narrated from the point of view of Ali, the father of the family, who survived the fire but stays in a mental hospital. Ali’s powerful characterization is the key strength of the play which creates the utmost sympathy in the audience. He is a responsible worker who is so naïve, kind-hearted and moderate that the bloody calamity of fire does not sow the seeds of revenge in his heart. Nowhere in the play does he express hatred for Germans and accuse them openly; instead, he tells his story with lighthearted humor and bitter irony which leave judgment to the audience. He describes the belittling job of collecting dog shit in the streets without victimizing himself and confesses that he does this job with great care and commitment. He also refers to his friendly relations with the Germans and his acceptance of a young German man as his son-in-law. All his explanations about himself and his life show that he has a responsible, considerate, and moderate personality.

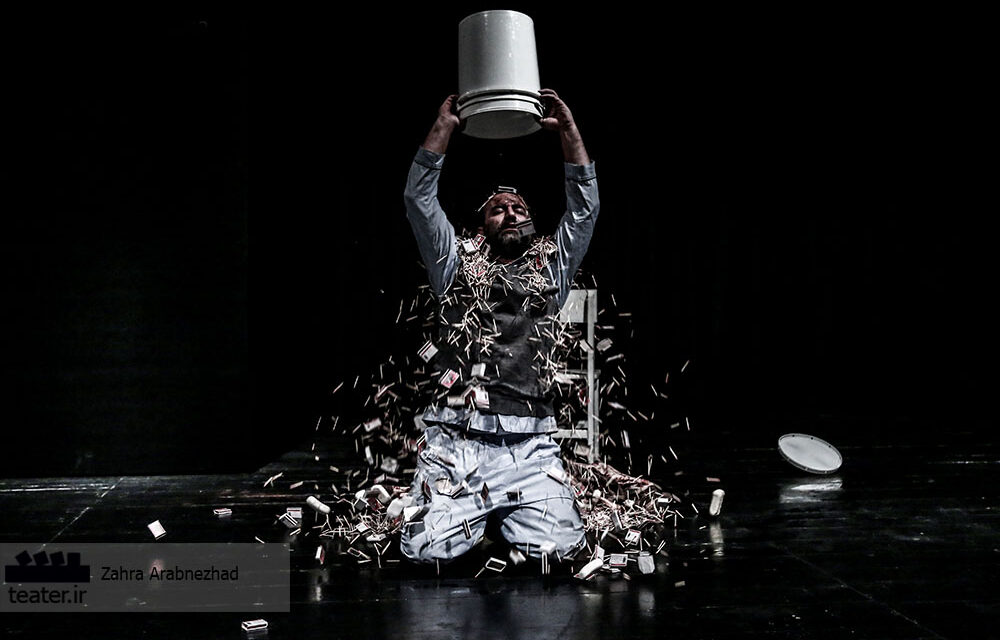

Misāgh Zāre in Barefoot, Naked, Heart in His Hand with the Burnt Caravan. Photo by Zahra Arab Nezhad.

While Ali does not play the victim, to illustrate his alienation and loneliness as an immigrant, Jalali distorts the syntax of the (apparently German) sentences that Ali uses while speaking. This has a comic effect, and at the same time creates a sense of pity in the audience. Throughout the play, tears and laughter are combined even in the most tragic scenes. The most memorable example of this is when Ali’s wife catches fire and screams “Help!” in a funny German accent, and Ali stupidly tries to correct her pronunciation. Watching the scene, the audience does not know whether to cry or laugh. In fact, this comic scene strikes a heavy blow against the audience, making them deeply understand the bitterness of the immigrants’ lives and the loneliness and helplessness which would burn in their hearts internally to the time of death.

The last blow falls in the final scene, when Ali returns home from the mental hospital and discovers that the elderly German woman, their kind neighbor, who is actually dead by now, has generously suggested sharing the apartment with Ali’s family, who are all alive and well, and they celebrate the wedding of Ali’s daughter and her German groom. It’s as if what has gone by now was only a nightmarish dream and the fire of narrow-minded racism has not destroyed Ali’s life and family. By choosing such a utopian ending, Jalali gives expression to his optimism about the future of humanity and his belief that “There is still hope and love will eventually defeat blind hatred and false prejudices.”

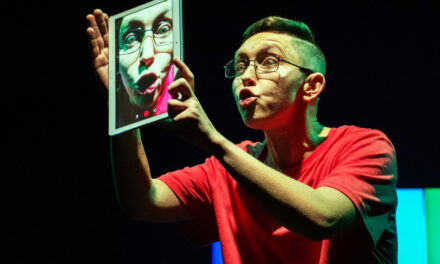

Selecting the right actor for Ali’s highly challenging role is obviously a decisive factor in the success of the performance. Misāgh Zāre performs this fast-tempo, sixty-minute monologue with outstanding verbal and physical dexterity and control. He speaks and acts with a breathtaking speed while instantly switching between the comic and the tragic throughout the play.

Reviewing Jalali’s work history, I realize that fast-moving tragicomedy and grotesque are his favorite drama forms. Such frameworks evidently need to create funny situations and atmosphere to achieve a comic quality. In Barefoot . . ., I observed that Jalali used humor and jokes in a more controlled and logical manner compared with his previous works, such as The God of Carnage, A Doll’s House, and Robinson Crusoe. In this way, he manages to maintain the artistic coherence of the play, which is, of course, a heartwarming achievement.

Compactness is another dominant characteristic of Jalali’s style which affects all parts of the play including the narrative, acting, stage design, and music. Choosing the form of a monologue performed only by a single actor is evidence of this, which results in the play’s richness and complexity. For this monologue, a minimal set is designed including very few objects with multiple functions. For example, there are some buckets that Ali uses both to clean the streets and to wash and dye the skin of his only surviving son white (to make him appear as white as a German). Besides these, there are a few other objects piled under a piece of cloth, which gives the illusion of a dead body lying under a coffin. A highly creative and unforgettable function of the set is when Ali suddenly pours a pile of matchboxes over his head while talking to the audience about his feelings. The scene reminds us of the calamitous fire which devoured his family and life, and the harshest expression of grief in the play which Ali, in most parts of the play, suppresses under the appearance of playfulness and a sense of humor. The minimal music, too, matches the compact form of a monologue. Between the scenes, short pieces of Persian traditional music are played which sound violent and suspenseful, and their fast tempo gives life and vibrancy to the monologue. In addition, a slow and sad Lebanese song is employed that intensifies Ali’s sense of loneliness and agony.

Barefoot, Naked, Heart in His Hand with the Burnt Caravan is an admirable work that is compact but rich, simple but complicated, comic but tragic, which more than anything owes its success to the wise and professional choices in directing, acting, set, mise-en-scene, and music.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Baharak Sahami.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.