As we bid the pandemic year goodbye and herald the new year, it’s worth asking about the kind of society Canada wants to be in 2021 and onward. I envision a country where people are not judged by the color of their skin or where they are coming from, but by the quality of their character and their humanity. Perhaps one of the things year 2020 taught me is to steadfastly work towards my envisioned Canadian society.

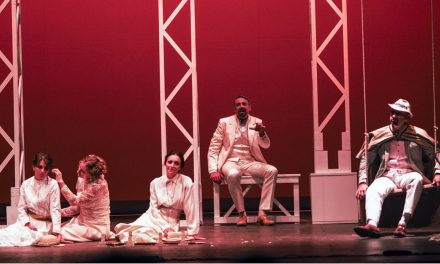

As an applied theatre scholar involved in socially engaged creative practice, I co-devised and directed a series of stage plays performed as a live interactive theatre performance honoring World Refugee Day, June 20.

The stage performance In the Footsteps of Our Immigrants was in response to the need to create brave and safe spaces for courageous conversations around immigrants’ experience because the question of identity is central to diversity and inclusion in the 21st century.

I drew on the power of storytelling I learned from theatre and an interest in critical questions about arts-based interventions. These informed my practice at Theatre Emissary International in Nigeria. Alongside my team, I created community theatre projects on social change.

We have continued to work in over a dozen countries across four continents. This same desire continued when I moved to Canada in 2015. I was interested in engaging with refugees, immigrants, and newly arrived youth because of the displacement I experienced during my undergraduate studies in Jos, Nigeria.

Theatre and social integration

In Canada, refugees and immigrants are integral to the workforce because their productivity boosts economic development. Paul Darby, the executive director of international programs at the Conference Board of Canada, estimates a shortfall of three million skilled workers by the year 2020. Refugees and immigrants are being eyed to make up for the shortage.

As of the end of 2019, 79.5 million people have been forcibly displaced worldwide. In 2018, Canada resettled 28,076 refugees through various programs — blended sponsorship, government-assisted, and privately-sponsored programs.

Canada considers diversity as its strength. How then can we support newcomers in the integration process? Theatre has been identified as a viable tool for refugee integration. The power of storytelling can facilitate dialogue and community building.

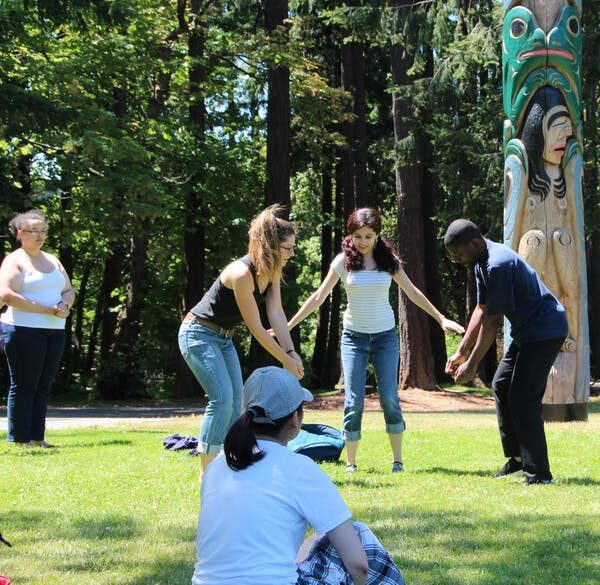

Standing, from left to right, Aziza Moqia Sealey-Qaylow, Leah Tidey, Serena Martin, and Taiwo Afolabi perform ‘In the Footsteps of Our Immigrants,’ at the University of Victoria quad, June 2018. (John Threfall)

Relocation and resilience

I directed and devised theatre performance that explored the narratives of newcomers, immigrants, and refugees about relocation, resilience, settlement, and integration in Victoria, B.C. The UN Refugee Agency has taken note of Victoria for its welcome to many refugees and immigrants.

In the Footsteps of Our Immigrants was based on immigrant and refugee stories of leaving their countries and arriving in a new country. We had stories of separations, monologues about names, language, and different encounters resettling in Canada.

It was created and played by actors and youths from various ethnic, religious, and cultural backgrounds who are interested in sharing their experiences as they navigate through the worlds of migration and resettlement. We had an interactive session at the end of every performance to engage the audience in dialogue.

The process involved using the people that were present to create a space where all participants’ voices can be heard in unique ways. As the director of the project, I facilitated an atmosphere to support immigrant youths and discuss issues.

On names and identity

One of the most common complaints immigrants make is how often their names get mispronounced. Participants identified names and identity, and language and accent as issues important to them. The play engaged both participants and the audience to reflect on why names matter.

Names connect people to their ancestry and origins. Through names, genealogy can be traced, and for some cultures and traditions, the future can be determined. Names go beyond identity; they are an embodiment of the past, present, and future. Names can connect people to culture and the naming process is considered sacred for some cultures.

Participants reflected on their own experiences about how their names were mispronounced, and how people are profiled based on their names and country of origin. A participant from China narrated his process of choosing a name when he arrived in Canada. He commented on how many Asian students find ways to rename themselves or find an English word that fits the meaning of their native names. Another participant from Syria narrated how a lecturer at a university in North America used his name to express her ignorance about Syria.

Many immigrants from Asia feel they must either shorten their names or adopt an English name when they arrive in North America because they face assumptions that their names are difficult to pronounce. Many writers use pseudonyms because of political conditions, gender, or racial discrimination; and due to crisis, some have to change their names so that they can belong to their present society.

Leah Tidey, Jasmine Li, Aziza Moqia Sealey-Qaylow, Taiwo Afolabi, Tianxu Zhao, and Sylvia Anatta perform ‘In the Footsteps of Our Immigrants,’ at the University of Victoria quad, June 2018. A seated audience member watches the performers and Emily Thiessen, project designer and videographer is kneeling. (John Threfall)

On language and accent

Participants expressed that language is not only a barrier in the discourse on diversity and inclusion; it is a metric for measuring who belongs and who does not. One participant who arrived in Canada as a refugee from the former Yugoslavia described repeated instances of people telling her she doesn’t “sound” Canadian:

“I always joke with my children, who are truly Canadian because they were born here: ‘It seems I can’t be a Canadian anyway even now when I am a citizen because of the way I speak.’”

Language is at the heart of people’s culture. Most immigration pathways to Canada require taking either an English or French language test to prove your ability. How many bypasses applying because they don’t yet score high enough?

It is important to state that this is not a criticism against the Canadian language testing system. After all, Canada isn’t the only country with such tests. Rather, it’s a consideration of what inclusion means within the ethos of language, communication, and diversity.

In the Footsteps of Our Immigrants shows that theatre can be a tool for community engagement. It is a way of using theatre as a medium to provide refugees and immigrants safe and positive spaces for self-expression as they settle in Victoria. Inclusion as an art requires a series of learning and unlearning processes for both newcomers and members of the host society.

This article was originally published in The Conversation on December 23, 2020, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Taiwo Afolabi.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.