Something flitters among the green leaves of bramble and the brown leaves of a previous autumn. There is movement, there is sound – the hum of traffic and a labor of breathing. Hands are seen manipulating objects in the undergrowth. A trowel is used to prod and dig at the earth. Feathers are carefully placed and covered with leaves. White hair protruding from a knitted red hat, the side of a head appears to inspect what has been done. The work continues. Hands stroke at the undergrowth, feathers are placed and covered with leaves; the sound of wind brushing through trees, accompaniment to audible breaths and the continuous scrabbling at the earth and leaves. A bespectacled face – a further inspection – the work continues. A feather is planted, other feathers are laid. A pair of lips primed with lipstick, a smile of satisfaction.

Up until this point, we have watched the performance Woodland Bird Woman in close up: as if, in the real space of the woodland where the majority of the enactment takes place, we are lying on the ground immersed in the action and the surroundings along with the performer. From this moment on, however, the intimate world of close up, where we participate with the performer, becomes viewing at a distance. The small movements – assertions and reassertions of objects – are replaced by the image of a figure, a woman clothed in turquoise and blue weatherproof clothing. She lies on the forest floor with her head close to the construction she has – we have – been working on. Upper torso bowed forward, legs spread and bent at the knees, she is a bodily swirl in a cosmos of autumn leaves and young spring ferns.

This action, where we are participants-cum-viewers of an intimate ritual, is the first five minutes of the film of a performance which was a collaboration between Esther Salamon and the artist Robert Laycock. From its intriguing beginning, which is given the subtitle ‘eye to ground, beetle, grass, moss, root’, the performance moves through three more parts titled ‘branches, leaves, feathers’, ‘she crouches’, and ‘laid to rest… laid to rest once more.’

In ‘branches, leaves, feathers’, Salamon substitutes the manipulation of objects in the undergrowth, to the hard physical graft of lifting branches to create what appears to be a large nest in a tree (big enough for a human?). Significantly, at points in the construction, feathers are added and Salamon cannot resist the temptation to place one in her hat – a badge of honor, perhaps, to the labor she has undertaken. In ‘she crouches’, the third and shortest of all of the performance’s parts, Salamon is seen, head bowed, kneeling beneath the arch of a tree branch that runs parallel and close to the ground. Surrounded by forest and persistent bird song, and now with many feathers in her knitted red hat, Salamon is in another nest, one that we have not seen her build.

In part four, ‘laid to rest… laid to rest once more,’ we watch as a protagonist lifts the window blinds of a conservatory and dresses to go outside. There is no art to this, the clothes – the weatherproofs we have seen in parts one and two of the performance – are donned as we would don them: a little shakily while putting on the trousers and slipping into shoes, and it is done against the backdrop of everyday life – radiator, furniture, wall clock, red floor tiles. We then follow the protagonist down the gravel path of a suburban garden out through the back gate into the woodland beyond. However, part four is not simply a continuation of what has gone before, because as it resolves the enigmas of parts one and two, it simultaneously poses questions.

To a great extent the resolution comes from a poem[1]I would like to thank David Stephenson for making a version of his unpublished poem, This is a performance, available to me. in voiceover recited by Salamon’s life partner David Stephenson, who takes over her role as the main protagonist. Stanzas one and two give us the context for the performance; it is of tree, bird and woman, where honor is given to the woman and we are asked to take notice of the birds:

And the tree gave, of its bark,

the likeness of a bird

to honour the woman.

Listen…

…as bullfinch brags his redness

against the sweet-trilling robin.

…to the crows and jackdaws, black in mourning.

…and every morning the meanness of sparrows,

because they truly can be mean.

It also describes what has (presumably) occurred in the performance prior to us joining it, as well as what we have actually seen. In stanza three, we are told:

We watch her ascend the briar path,

see her step aside the nettles

until she reaches the nest she fashioned:

branches, leaves, feathers.

She crouches,

eye to ground, beetle, grass, moss, root.

Meanwhile, stanza four reveals the backstory to the events we have witnessed. This involves an ‘unusual activity’ in which, as a child, Salamon found dead birds in the street, placed them in the basket of her bicycle, and then took them back to her mother’s garden where she buried them:

Her first bird was many decades ago,

laid to rest in the basket of her bike,

ridden home, then laid to rest once more

in her mother’s garden in Detroit, Michigan.

It’s not only god who sees

The meanest sparrow fall.

This tallies with what the creators of the performance have written about it.[2]In a leaflet advertising a presentation of the filmed performance at Newcastle Contemporary Art in Newcastle Upon Tyne, 26th and 27th September 2025, the films creators wrote: “The origins of the … Continue reading However, there are depths of meaning to the performance that are only revealed as part four continues: it includes allusions to absence and death but also in the acknowledgement of these, the assertion of presence and life. These binomials and the complexity they uncover is signalled in a number of ways. Salamon is not present in part four, Stephenson takes her place. His presence marks her absence which is due to her untimely death.

Part four of the performance continues. Stephenson walks down the gravel path to the end of the garden into adjoining woodland. However, before he enters, he does a number of things: in different clothes, he places a bird mask over his eyes and nose and, with both hands, picks up a yellow-green wax effigy of a girl or woman bedded on a small nest of straw; simultaneously, now in Salamon’s clothes, he puts on her knitted red hat with feathers and picks up a nest with a dead bird lying across it. Because this is a filmed performance, the effect of Stephenson being both bird and Salamon is achieved by cutting between and editing together the two separate figures as the rest of the episode unfolds: Stephenson (bird/Salamon) proceeds into the woodland where he places the effigy in the crux of a tree and the bird at its base, and covers it in leaves. Stepheson stands by the tree where he has placed the bird and the effigy and then he is gone.

The act of placement is a ceremony that follows a prescribed order. It recalls Salamon’s act of burying dead birds in her mother’s garden as a coping mechanism for her life as an immigrant child and a way to deal with stories of the Holocaust which she grew up with. It also recalls what Salamon was doing in parts one and two of the performance. Represented by the effigy, Salamon herself is now woven into those forms of remembrance, the acts of burial and storytelling, as well as her own “reenactments” of them. The final stanza of the poem alludes to the absence of the living by breaking down life into its constituent parts ‘bone’, ‘blood’, ‘carbon’ and ‘water’, but then, in spite of this, reasserts life – perhaps, in the form of a bird: “And some of us fly”. Salamon’s presence is assured. The final stanza is voiced as follows:

For we are all made of the same stuff:

we are bone, we are blood,

we are carbon, we are water.

And some of us fly.

Stephenson puts a bird mask over his face, places a red knitted hat decorated with feathers on his head, picks up a dead bird in a nest and then an effigy. Source: Woodland Bird Woman.

As part four moves on to its conclusion (and the conclusion of the performance as a whole), there is a shift in relation to what is enacted, who is performing and where it is done. Salamon and Stephenson make way for operatic vocalist Alison Barton and the aerial performer Freya Averly. Barton sings the aria from Dido’s Lament – When I am laid in earth – from Henry Purcell’s opera Dido and Aeneas (1688). It is sung in Baroque pitch, half a semitone lower than present-day performance, without accompaniment. This means the voice is deeper, richer and, because there are no instruments, a range of emotions can be heard – sadness and despair but also strength and determination. Barton’s delivery captures the depth of feeling connected with the tragic story told in the opera but it is also an exaltation to remember and honour the life of Salamon in her death:

When I am laid, am laid in earth,

May my wrongs create

No trouble, no trouble in thy breast;

Remember me, remember me, but ah! forget my fate.

Remember me, but ah! forget my fate.

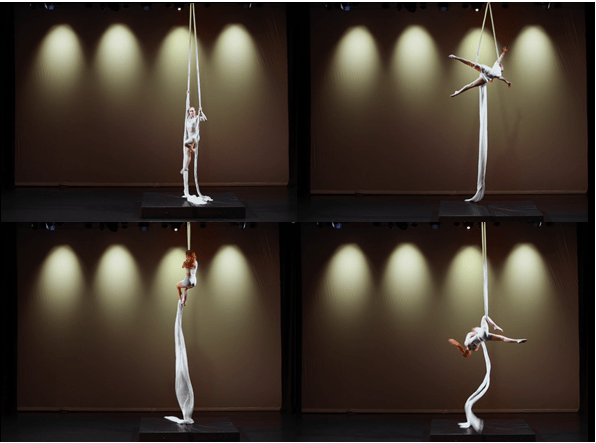

The first three lines of the aria are repeated twice, followed by a double repetition of the two final lines. This division of the aria is acknowledged in the aerial performance choreographed and performed by Averly. For the first three lines and their repetition, she works her way up two narrow bands of fabric which hang down from the ceiling to the floor. For the two final lines and their repetition, she descends. The choreography and its execution matches, movement by movement, the tempo and magnificence of Barton’s singing. In the ascension, Averly “walks” her way up the silks, stops, stares upwards to the left, swings as if ready to vault, but falls back. After this reversal, she uses her arms to confidently pull herself up until, almost at the top of the bands and entwined within them, she moves from an upside down to a sitting position. There is a pause here, as if she is taking in a view before extending her arms and legs into a star shape. This is the pinnacle of the ascension: the bright, burning culmination of a life. Averly attempts to maintain this height, to climb higher even, only to, inevitably, fall into a slow controlled descent, down to the ground. Throughout the whole of her enactment, Averly displays supreme control over body and silks to deliver a performance which is, together with Barton’s singing, mesmerizing.

Mention should also be made of the place in which the aerial performance is enacted.

It is an indeterminate location: an abstract space consisting of a plain backdrop defined by four evenly situated downlights with the silks placed off centre to the right of the scene. The colours are autumnal, muted tones of brown and beige framed by the black of the stage’s floor and its periphery. It is complemented by the off-white of the silks and Averly’s costume, as well as her auburn-red hair. This gives the final part of the performance an “other worldly” dimension. And, even though the movement through the silks is extremely physical and the singing powerfully wrought, the effect achieved takes the enactment of Woodland Bird Woman from the physical onto the metaphysical plane.

Sound too is an important component of the performance and works across different levels. There is Barton’s rendition of Dido’s Lament and Stephenson’s reading of his own poem about Salamon. These are intentional elements of the soundscape that impart narrative and add to its emotional weight. There are, however, incidental sounds, but these do more than simply accompany the action. They reveal deeper truths about what is occurring, concerning place and the intensity of engagement: Salamon’s grunts and sighs or the humming she indulges in as she works away at her task; the sound of the wind pushing its way through the trees or the low murmur of unseen traffic; the power of the birdsong when Salamon crouches in the woodland; the swish of material as Stephenson opens the blinds in the conservatory or puts on Salamon’s clothing, as well as the crunch of stones as he negotiates the gravel path in the garden; and finally, the barely heard expressions of exertion from Averly as she climbs and then falls through the bands of silk. All of these add an extra layer of veracity to the performance and ensure it is a rich audial as well as visual experience.

Averly ascends, bursts into a star shape, ascends even further and then goes into descent. Source: Woodland Bird Woman.

The premier of Woodland Bird Woman, took place at the Between.Pomiędzy Dispersed Festival 2025. The festival is an annual event known for staging original performances across genres that often defy strict classification. This filmed enactment follows on in that tradition. It is reliant upon the skills of two performers guided by Laycock and the expertise of an operatic vocalist and aerial performer. It is also dependent on the talents of the technical team that supported them in the making of the film: in particular artist and creative producer Matt Denham, who oversaw video and audio recording of the aerial performance and post production of the film overall.[3]Other members of the technical team that helped create the film of the performance include: spoken word audio, Subwaves Music Studios; operatic vocal recording, David Puttman, Media Centre, … Continue reading It is a visually rich production that intrigues with its attention to small details and also its effortless shift from the natural world through the surroundings of everyday life and home, to a symbolic world of mask, bird and effigy and, finally, into the metaphysical realm created through the performances of the aerial “dance” and the sung lament.

It is the second time artist Robert Laycock has cooperated with the Between.Pomiędzy Dispersed Festival. In 2024, he presented two delegated performances – Wdzydze Tucholskie Lake Swim and About Love: 1000 Contemplations – in which he gave instructions for the performances and other people enacted them.[4] In Wdydze Tucholskie Lake Swim, Laycock was not present and the participants followed a set of instructions to swim in a lake written by the artist. The second performance, About Love: 1000 … Continue reading It was the first time a performance by Salamon was presented at the festival and only the third performance she created before her death in 2023. Encouraged by Laycock to develop ideas that had lain dormant in notebooks since the early 2000s, Salamon envisaged Woodland Bird Woman as a multi-media performance in which a memory of the childhood experience described in stanza four of Stephenson’s poem is transposed to create an enactment where “[t]he activities and the music juxtapose the real with the surreal and aim to provide the audience with an opportunity to consider notions of death, ritual/memory and remembrance.”[5]Quote taken from a leaflet advertising a showing of the performance at Newcastle Contemporary Art in Newcastle Upon Tyne, 26th and 27th September 2025. The filmed performance presented at the Between.Pomiędzy Dispersed Festival 2025, certainly achieved that aim. And, it is due to the determination of Stephenson and Laycock that Salamon’s project was fully realized. In this case, therefore, referring to Laycock’s previous performances for the festival, if they can be classified as delegated performances, then Woodland Bird Woman might be described as facilitated performance; where the artist’s knowledge and skills have been used to support a fellow artist in the realization of her artistic vision.

This article is part of the report on Between.Pomiędzy Festival 2025, available on TheTheatreTimes.com.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Martin Blaszk.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.

Notes

| ↑1 | I would like to thank David Stephenson for making a version of his unpublished poem, This is a performance, available to me. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | In a leaflet advertising a presentation of the filmed performance at Newcastle Contemporary Art in Newcastle Upon Tyne, 26th and 27th September 2025, the films creators wrote: “The origins of the piece lie in the experiences of Esther herself, a child-immigrant to the USA in the mid-1950s. Daughter of Holocaust survivors, she was brought up on stories of death and orphaned children, which she reinterpreted in the light of her late childhood in Detroit. To survive existentially she had to assimilate to the new culture but remained true to her own nature. The ‘unusual activity’ of which she speaks refers to her finding dead birds in the street, placing them in the basket of her bicycle, then taking them back to her mother’s garden for burial. It was an image that never left her, one that grew in her artistic imagination to encompass all the unclaimed dead.” |

| ↑3 | Other members of the technical team that helped create the film of the performance include: spoken word audio, Subwaves Music Studios; operatic vocal recording, David Puttman, Media Centre, Sunderland University; aerial performance filmed at Dance City, Newcastle Upon Tyne. Robert Laycock and Esther Salamon were responsible for camera and sound on all other parts of the film. Robert Laycock and David Stephenson were producers of the performance and the film. |

| ↑4 | In Wdydze Tucholskie Lake Swim, Laycock was not present and the participants followed a set of instructions to swim in a lake written by the artist. The second performance, About Love: 1000 Contemplations, took place over three sites enabled by the use of a video conferencing app. It was devised by Laycock in collaboration with the life coach Dr Julie Scanlon who led the performance: Scanlon read out twenty questions relating to love and participants registered their responses by writing or drawing on a piece of paper. A detailed description and analyses of these performances in Polish can be found in the journal Konteksty 2/2025 (349). A copy can be downloaded from https://czasopisma.ispan.pl/index.php/k/article/view/4359 |

| ↑5 | Quote taken from a leaflet advertising a showing of the performance at Newcastle Contemporary Art in Newcastle Upon Tyne, 26th and 27th September 2025. |