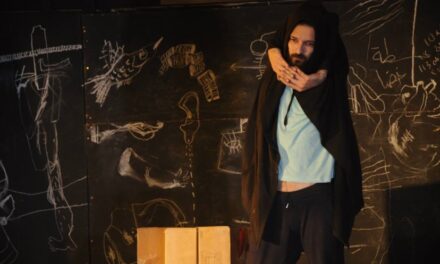

Passing through Mumbai last week was Japanese composer Yasuhiro Morinaga. Arts aficionados in India would know of him through his collaborations with the Delhi-based choreographer Mandeep Raikhy, having scored the music for productions such as A Male Ant Has Straight Antennae (2013) and Queen-Size(2016). His work in the performing arts is a sideline to a thriving career as a music director in feature films and documentaries, as well as his well-regarded detours into ethnomusicology—Morinaga’s ongoing research into Asian gong culture has resulted in the excavation of musical artifacts that are marked for their anthropological and cultural significance.

Generating sound

During his previous trips to India, Morinaga hadn’t really ventured beyond Delhi. The projects with Raikhy had involved tight timelines, leaving no room for travel. This time round, when the Japan Foundation came knocking with another project—once again with Raikhy—Morinaga requested an itinerary that would allow him to travel and see more of the country.

“This is really my first time traveling through India,” says Morinaga.

In Mumbai, the composer conducted a workshop on field recordings, titled Sonic Explorations, that was organized by the Mumbai Assembly, a cultural organization that is fast emerging as a valuable site for cross-cultural arts pollination.

Early echoes of Raikhy’s political new work, Pray, were perhaps seen in Long Nights Of Resistance, night-long performances that took off from the nationwide “Not in My Name” protests. Collaborators on that project made use of American composer Steve Reich’s Come Out, a searing 1996 musical collage in which fragments of real-life testimonies of black men accused of murder were used to create a powerful and resonant tapestry of sound.

Of particular political significance was the sentence, “I had to, like, open the bruise up, and let some of the bruise blood come out to show them,” attributed to Daniel Hamm, one of the accused. For his new production, Raikhy wanted Morinaga to work with the found footage of a similar recording from Gujarat.

“I find Reich’s style of minimal music closely related to the music of Asia or Africa,” he explains.

He did not necessarily want to emulate Reich’s system of composition, but was keen to explore new technology.

“At times, we spliced the sample into pieces and let the computer generate certain sounds,” he says.

Not understanding Hindi was a challenge, but Morinaga took his time to understand each word and its political implications.

Mapping music

Morinaga’s earlier collaborations with Raikhy involved the creating of music for dance set pieces. These were surreal and soulful scores that were accessible and aimed at appealing to most audiences. In Queen-Size, the looping of musical interludes, alongside a performance in perennial iteration, lulled audiences into an uncommon experience of public intimacy. Pray marks the first time the composer has worked with both text and music to create a soundscape that is gritty and political, in which the emotional power of actual speech is retained by a composition that is no less intricate and striking in its own right.

A workshop on music ethnology at the Busan Film Festival steered Morinaga towards his current preoccupation–the cultural roots of music. The longitudinal stretch from Japan to Indonesia always presented to him the conundrum of shared cultures divided by unwanted political boundaries.

“Japan is four islands, and so is Indonesia, yet as we move southwards from one archipelago to another, we find shared characteristics in music,” he explains.

This is particularly true of the culture of the gong, the Asian percussion instrument. Excavating these connections have led Morinaga to work with myriad ethnic minority groups across countries—like the Co-Ho people of Vietnam. While creating a map of this shared musical genealogy, Morinaga has also brought back rare recordings and extensive research into both musical and cultural mores.

“It takes time building trust, but that is important because I am taking their culture in a way,” he says.

Sonic interludes

In India, Morinaga is struck by the level of sound in everyday life—traffic, markets, crowds—both in terms of decibels and intensity.

“In Tokyo, we have alternatively quiet and loud spaces,” he says.

One of the exercises at his workshop required participants to record audio samples of the urban environment.

“I wanted them to find aural spaces where the background becomes the foreground, and where it recedes to the backdrop,” he describes.

Using that method, he explains, it could be possible to access a sound not just for itself, but through the memories or cultural contexts it evokes.

This article originally appeared in The Hindu on August 15, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Vikram Phukan.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.