The Eighth Life (for Brilka) or Das achte Leben (Für Brilka). Adapted by Julia Lochte and Emilia Linda Heinrich from the novel by Nino Haratischvili. Directed by Jette Steckel. Costumes by Pauline Hüners. Scenic design by Florian Lösche. Video by Zaza Rusadze. Choreography by Yohan Stegli. Music adapted by Mark Badur. Photography by Armin Smailovic. Cast: Franziska Hartmann, Mirco Kreibich, Karin Neuhäuser, Barbara Nüsse, Sebastian Rudolph, Maja Schöne, André Szymanski, Cathérine Seifert. World premiere: April 8, 2017, at Thalia Theater in Hamburg, Germany. Seen in Saint Petersburg during the International Theatre Olympics 2019.

While some theatre experts are still discussing whether there is a place for full-fledged plots and narratives in the contemporary theatre, director Jette Steckel and Thalia Theatre argue convincingly that any piece of literature, despite its volume and size, can be transformed into the language of the stage. The play The Eighth Life (for Brilka) is based on the novel of the same name by Nino Haratischvili. The book is a monumental canvas (over a thousand pages) that covers the lives of six generations of a family from the 1900s to the 2000s, chronicling a series of great changes and shattered hopes.

This story seems very personal for Haratischvili, and, in a way, it is a civic action. A playwright, director, and prose writer, and winner of literary and theatre awards, Haratischvili was born in Tbilisi in 1983. She left with her mother for Germany at the age of twelve, but she returned to Georgia a few years later, and after some time she led a theatre group there. It staged performances in two languages: Georgian and German. She studied at the Tbilisi State Institute of Theatre and Cinema. Currently, she lives in Germany. In 2010, Haratischvili was named laureate of the Adelbert von Chamisso Prize, which is awarded to authors writing in German, whose work is affected by changes in the cultural environment. The Eighth Life (for Brilka) was published in 2014 and dubbed by the press the best German-language novel of the year. The book has been honored with the Anna Seghers Prize, the Lessing Prize Stipend, and the Bertolt Brecht Prize.

The history of a family and the history of a man at the turn of an era—this is the quintessence of the novel and the performance. Not only do voices from the past come to life in it, but the signs of this very past are visible in our present life. This is the view of a person looking at the past, at times with nostalgia, at times with horror, seeking to understand the roots and causes of the world’s challenges and one person’s difficulties. This is a man who always feel alone before the judgment of History and Time.

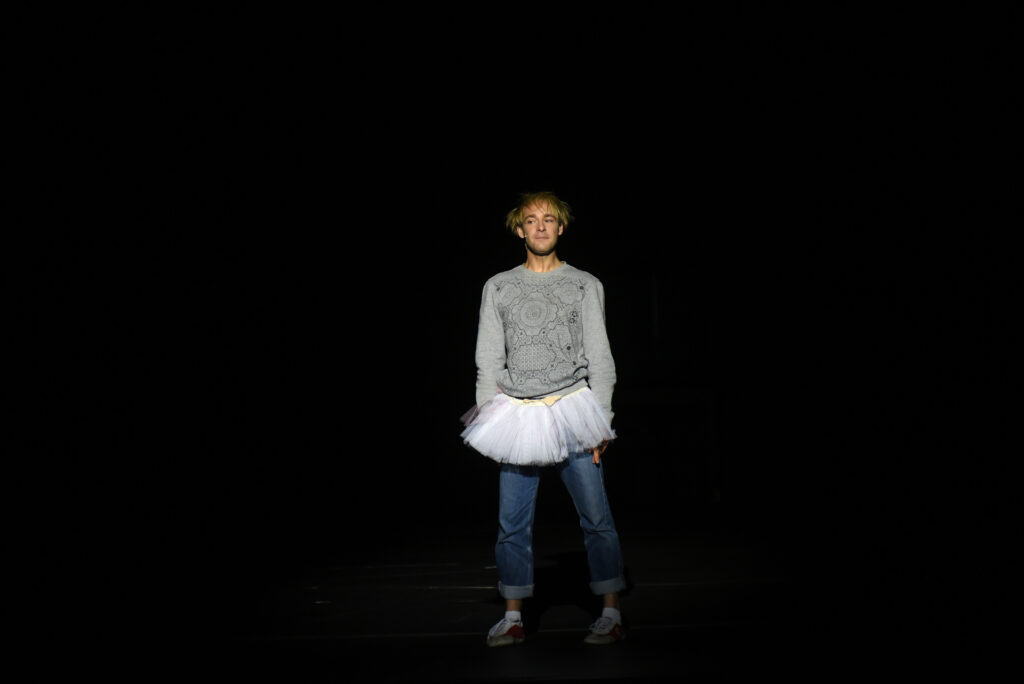

The Eighth Life (for Brilka). Director Jette Steckel. Thalia Theatre, Germany, 2017. Photo: Armin Smailovic from Theatre Olympics Press Service 2019.

Without a doubt, the book might become a movie. Its real historical figures and fictional characters are united by what has befallen them: the difficult times of revolutions and wars. The novel shows everyday life and political intrigue, ordinary people and the Powers That Be, and the plot catches its reader and immerses them into the past completely.

The author of the novel chose as her epigraph the words of Russian poet Anna Akhmatova (also a victim of the era), from her poem Requiem: “No, not under the vault of alien skies / And not under the shelter of alien wings — / I was with my people then, / There, where my people, unfortunately, were. / Stabat mater dolorosa bent over each of the heroes of the play, as if.” The characters’ stories are so vivid and fascinating that any of them—the women (Stasia, Christine, Kitty, Elene, Daria, and Nisa) or the man (Kostya)—could be a separate novel or performance piece. The characters are convincingly and reliably played onstage. In the five hours of the performance, you feel that you can treat them like your family circle. The novel conveys a powerful message about the human spirit and endurance.

From London to Berlin, from Vienna to Tbilisi, from St. Petersburg to Moscow, the romantic and tragic fate of members of the Georgian family is closely connected with the dark episodes of twentieth-century history and is peppered with magical realism. The novel hurts; it has a lot of pain. This story tells of betrayal and resistance, love and hate, dreams and disappointments, a strong desire to live and survive amid social upheaval, suicide, abortion, torture, and horror. Losses, triumphs, sorrows, and great love are opposed to the sweep of history.

The Eighth Life (for Brilka). Director Jette Steckel. Thalia Theatre, Germany, 2017. Theatre Olympics Press Service 2019. Interpress

The story is written on behalf of Nisa, a Georgian woman that lives in Germany in 2005. Her twelve-year-old niece Brilka runs away in search of answers from her dance troupe during a trip to the West, and Nisa goes in search of the girl. These searches simultaneously turn out to be a quest for their own identity. Nisa decides to write in black and white the story of her family, starting from the moment her great-grandmother Stasia was born, in 1900.

The novel opens in a small town between Georgia and Azerbaijan, a town with the potential to be “the Nice of the Caucasus.” A gifted chocolatier in the town comes up with a unique, secret recipe for a hot chocolate drink with extraordinary properties (a circumstance that recalls the novel Chocolat by Joanne Harris). Georgians or others who lived in the Soviet era might associatively recall the famous Lagidze water, a Georgian soda that still exists today. The chocolate drink makes people swoon, and those who have tried it wish to drink more and more. The chocolate can be sold only in small portions, suggesting that happiness, too, is something that should be sipped, not gulped. This mystical drink becomes a symbol in the story.

A small enterprise grows into a large confectionery factory, which opens up many new opportunities for the chocolatier’s four daughters, who are raised in high society and live in luxury. Stasia (Barbara Nüsse), the eldest one, dreams of living in Paris and becoming a ballerina, but not all dreams come true. At seventeen, she married White Guard lieutenant Simon Jashi, who transfers to Petrograd on the eve of the October Revolution, far from his wife.

After a short stay in Odessa with her husband, Stasia returns to her familial home and gives birth to a son, Kostya. The chocolate business, meanwhile, has been taken over by the Bolshevik state. The secret ingredient is no longer added, and their taste has changed. The taste of time has also changed, becoming bitter. Stasia’s husband returns home as a deeply damaged and crippled man. Stasia is forced to work hard on a farm. Dreams of dancing, love, and family happiness are over.

The Eighth Life (for Brilka). Director Jette Steckel. Thalia Theatre, Germany, 2017. Photo: Armin Smailovic from Theatre Olympics Press Service 2019.

When Stalin becomes the sovereign leader of the Soviet Union, Stasia and her children seek refuge in the Caucasus, in the Tbilisi home of her younger half-sister Christine (Maja Schöne). While party leaders enjoy their good life, the country’s poor suffer from totalitarianism and oppression. Christine loves her husband, businessman Ramas, who generously gives her presents. They enjoy a social life in their luxurious villa.

Stalin’s right- hand man(probably Lavrentiy Beria, although he is not directly named) is drawn to the beauty of Christine, and disaster strikes the sisters’ house. Out of fear, Christine agrees to become his mistress. Having received the title of Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Georgia, her lover oversees the mass peasant deportations and executions prescribed by the Stalin Kremlin. That leads to tragic events for the whole family.

“I owe these lines to you Brilka because you deserve the eighth life. Because they say the number eight represents infinity, constant recurrence. I am giving my eight to you,” writes Nisa. Brilka (Cathérine Seifert) is the last descendant of this family, born in the new independent Georgia in the 1990s. In her is the hope of the family, the hope of the whole country for a new generation that should remember the past and yet get free from their ghosts.

The Eighth Life (for Brilka). Director Jette Steckel. Thalia Theatre, Germany, 2017. Photo: Armin Smailovic from Theatre Olympics Press Service 2019.

Hamlet says that “the time is out of joint,” and it certainly is for these people who survived the Civil War and World War II, the coming to power of the Communists, the Stalinist repressions, the Iron Curtain, the struggle for Georgian independence, the collapse of the USSR, the difficult birth of post-Soviet democracy. Together with them, readers (and viewers) love and suffer, find and lose, deceive and forgive, find the strength in themselves to move on further and just live.

Jette Steckel and stage designer Florian Lösche created an original stage space. The scene is dominated by three colors of the era: red, black, and white. The symbolism of these colors continues in costumes created by Pauline Hüners. At the back of the stage hangs a giant carpet with a traditional Georgian ornamentation, about sixty meters long. On that makeshift screen, thanks to video projections, the outlines and portraits of the era appear. The carpet is like a newsreel screen. Documentary footage related to each era (video by Zaza Rushadze) is shown in parallel with the actions of the actors on stage. Military scenes, demonstrations, happy childhood days in the Soviet Union, and communist marches—hours pass in the theatre hall, but, in fact, it is decades. At the tragic moment of the terrible pages of world history, the carpet will curl up and fill the room into a river of blood, which will become a river of tulips then. To this day, Georgians bring these flowers to memorials in memory of Tbilisi tragedy victims. Each family member is a separate thread of bright or dark color, uniting into a common picture—a canvas of history. Fate and threads of fate intertwine here.

However, the production’s external effects, the detailed choreography (Yohan Stegli), and an abundance of video overwhelm the audience’s perception, overloading it. Actors get lost in the multilayered space of video, sound, and dance, and the essence of the text becomes hazy. Haratischvili’s text as adapted by Julia Lochte is artistic and needs no extra context; it creates vivid images in the audience’s imagination. But the performance is so extravagant that the director simply does not leave space for spectators’ imagination. Obviously, the creators of the play did their best to convey a family epic and a chronicle of the century through the spectacular, but they simply lost a sense of measure. The performance is full of emotional paths and various visual effects. The rhythm of the prose is broken.

The Eighth Life (for Brilka). Director Jette Steckel. Thalia Theatre, Germany, 2017. Theatre Olympics Press Service 2019. Interpress

The performance develops in a zigzag way, but the repetitions of artistic techniques is tiring. Where the fort sounds are in the novel, the stunning fortissimo is in the play. It seems that the actors rush from one extreme to another. But what makes a strong impression is that the novel does not work onstage. The director tries to assault the audience’s emotions as much as possible, but in the end, the audience just gets tired, as the scenes are layered on top of each other. A repulsive pathos arises in the play, one that is not in the book. The fever and desire for entertainment here, at times, replace the intimacy of family drama.

Despite all the artistic imperfections of the performance, it is without a doubt one of the highlights of the Theatre Olympics 2019. It acquaints viewers with an amazing text, comparable to the epic narratives of Leo Tolstoy, Buddenbrooks by Thomas Mann, Vasily Grossman’s Life and Fate, One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez, and The House of the Spirits by Isabel Allende. It is also important that at this time of tense political relations between Russia and Georgia, this performance has found its way to the public, recalling that, despite difficult past events, there is always hope for a peaceful future. Meanwhile, a bit earlier, in Kutaisi, Georgia, a rally was held against the arrival of the troupe of the Moscow-based Nikitsky Gate Theatre. Director of the theatre Mark Rozovsky brought the production Forget-Me-Nots based on the play by Lyudmila Ulitskaya to Kutaisi. The artistic director of the Kutaisi State Drama Theatre Kote Abashidze, in turn, called the rally “the result of an information vacuum.” According to him, “the creative friendship between the two theatres has nothing to do with politics.”

The great Russian historian V. O. Klyuchevsky once said: “History does not teach anything, but only teaches somebody a lesson for ignorance.” The actors on the stage revolve in a frantic whirlwind of history, and an idea strikes then freezes: if only not to repeat the hellish circles of the past, just not to repeat…

The Eighth Life (for Brilka). Director Jette Steckel. Thalia Theatre, Germany, 2017. Theatre Olympics Press Service 2019. Interpress

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Emiliia Dementsova.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.