Le reste vous le connaissez par le cinéma written by Martin Crimp, translated by Philippe Djian and directed by Daniel Jeanneteau, is among the most politically urgent works in the Avignon 2019. Not only that it builds on the enigmatic and ever-wise text of Martin Crimp, but it also references the new realities of today’s France with its over-populated banlieues that drastically redraft the face of the country’s cities.

An adaption of Euripides’ tragedy The Phoenician Women that was itself a take on Aeschylus’ Seven Against Thebes, Crimp transforms the old Greek story into a thesis play with the Chorus center stage. In this version of Oedipus’ myth, Jocasta does not kill herself. Upon learning the truth of her son/husband, she lives to see his shame and her sons’ death. The play opens with Jocasta’s account of the past and a warning that the guilt of the parents does not simply go away. The blind Oedipus, locked up by his sons Eteocles and Polyneices, has cursed them for this deed. He declared that neither of them will rule the city without his brother. Now, Polyneices, who exiled himself to Argos and married a foreign woman, has returned to Thebes to claim his inheritance. Eteocles is of course not interested in sharing power. After a short mediation between the brothers organized by Jocasta, they resume the fight and kill each other.

As any adaptation of Greek myth that reflects the fall of the empire or the troubled times of political shifts – I’m thinking here of Jean-Paul Sartre’s adaptions of the Greek tragedies – both Euripides’ tale and Crimp’s play question the place of the authority, the political figures and powers that are in charge of people. People, in this context, emerges as a separate if not leading character, whose extensive commentary frames the conflicts between the protagonists.

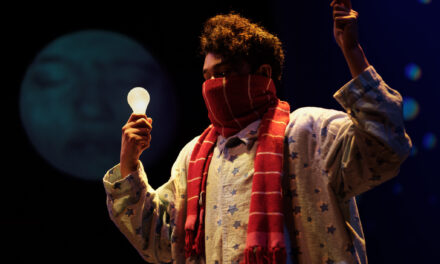

In Daniel Jeanneteau’s staging, the character of the people is enacted by a group of strangers – young women from the banlieues of Gennevilliers. They are today’s Phoenician women, who in the original story were journeying to Delphi but got trapped in Thebes because of the war. These ultimate strangers, as the director states, are found in the middle of the conflict by chance and against their will, they “observe power and society with a critical and intelligent eye.” For them, time seems to have stopped. Stuck in the nowhere of their journey, they play games and ask riddles, they question the logic of the world they observe and challenge the authorities. They also ally with the young, like Antigone, who are to carry the burden of this world further; and they enact rituals – like the one of sacrifice.

The physical and aural presence of this multicultural and multi-accented chorus is juxtaposed with the impeccable work of Dominique Reymond as Jocasta. She enacts the shame of the woman who committed a crime and the pain of the mother who knows that she will lose her children with the consuming power of Greek tragedy. Every word Reymond says and every gesture she makes bares the weight of the impossible. The Chorus listens to Jocasta’s lamentations attentively; it does not interrupt her speech. Perhaps in its ability to foresee the future – the power of the sphinx this Chorus also enacts – the women/strangers understand Jocasta’s pain only too well, they share her burden even if they do not say so.

Philippe Smith as Creon is also very interesting. In his role of the devoted city functionary, he reminds of another Creon, now from Jean Anouilh’s Antigone written in 1944, during one of the darker periods of French history. Smith’s Creon is the only character who wears a tie. An adult of this story, he makes one decision after the next; but he also faces the improbable. To save the city he must sacrifice his son. Creon refuses to take this step, he asks Menecee to run away, to become an exile. I’m a man – the boy responds, making the only decision he can in this universe of a spoken fate.

One way or another, the Chorus is always present on this stage. It reminds the characters and the audience that a theatre play, specifically the one based on the models of the Antiquity, is, as the director Daniel Jeanneteau proposes, “a device, an arrangement, and a machine which produces life”; most importantly it is the tool that “arouses very modern thoughts.”

Le reste vous le connaissez par le cinéma by Martin Crimp

Translated by Philippe Djian

Direction, stage design: Daniel Jeanneteau

Assistant direction, dramaturgy: Hugo Soubise

Artistic collaboration and choeur: Elsa Guedj

Dramaturgic adviser: Claire Nancy

With Solène Arbel, Stéphanie Béghain, Axel Bogousslavsky, Yann Boudaud, Quentin Bouissou, Clément Decoutalternating with Victor Katzarov, Jonathan Genet, Elsa Guedj, Dominique Reymond, Philippe Smith

Chorus by Delphine Antenor, Marie-Fleur Behlow, Diane Boucaï, Juliette Carnat, Imane El Herdmi, Chaïma El Mounadi, Clothilde Laporte, Zohra Omri

Production T2G – Théâtre de Gennevilliers Centre dramatique national, in co-production with Théâtre national de Strasbourg, Ircam – Centre Pompidou, Festival d’Avignon, Théâtre de Lorient Centre dramatique national, Théâtre du Nord CDN Lille Tourcoing Hauts-de-France, and support

of Région Île de France, Fondation SNCF

Gymnase du lycée Aubanel, Avignon Festival, July 16-22, 2019

This article was originally published on http://capitalcriticscircle.com. Reposted with permission. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Yana Meerzon.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.