To those who feel overexposed to Waiting For Godot—which includes many theater snobs—no text-faithful production may ever fully satisfy. A great many worldly people yawn nowadays at the play as written. They’ve seen enough Didis and Gogos who wear the requisite grubby clothes and boots and move among objects that actually resemble a tree and rock. For them, the desolate, unaccommodated stage picture Beckett made famous has become a cliché, the existential malaise performed in it something like a postwar platitude.

Some of these people are aficionados of the continental European practice of Regie—a word usually translated as “directing,” though its practitioners regard it as an autonomous art form in which playtexts may be treated as boundlessly malleable material—like sound, light, and color. Regie fans would no doubt have preferred that Lincoln Center’s White Light Festival had invited, say, Dagmar Schlingmann’s 2015 Godot from Saarbrücken, in which the set was a pile of discarded modern clothes (which Lucky tried on) and the background was a large photo of a seascape. Or Ivan Panteleev’s 2014 Godot from Recklinghausen, in which Didi and Gogo appeared to land by parachute in an angular crater on an alien planet, out of which Pozzo and Lucky later emerged.

In the event, the Festival invited none of these productions but rather the Druid Theatre Company’s eminently faithful Godot, directed by Garry Hynes. This production is rooted in the enduring yet perpetually un-chic Anglo-American tradition of directing as a sensitive and loving artistic service to the playwright. If you are open to such a production’s virtues, please take my word that this one is not to be missed.

The acting, for one thing, is positively limpid. The compulsive game-playing between Aaron Monaghan (Estragon) and Marty Rea (Vladimir) is so fluid and convincing it could only have come from a thoroughly organic development process involving actors riffing off each other’s inspired comic habits and peculiarities. Strangely enough, all their antics feel lifelike even though the whole play is choreographed into tight mobile patterns and physical gags like those Beckett employed when he directed it in 1975. Rory Nolan’s Pozzo is another delight—a tightly wound, roly-poly, insecure gasbag whose hypersensitivity makes hilarious sense of countless lines that you may have assumed were hopelessly murky.

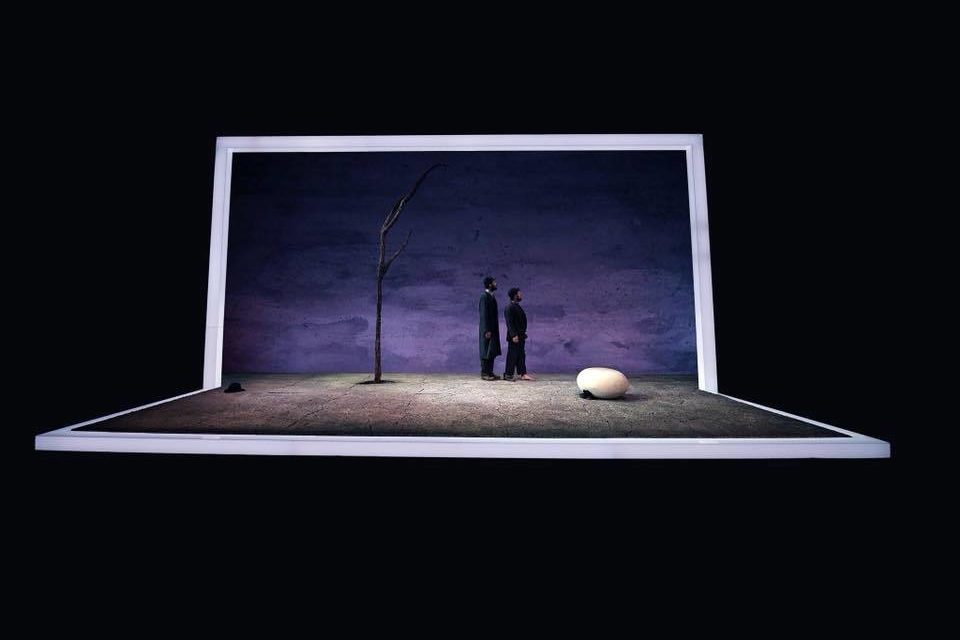

The show is also stunningly designed. Francis O’Connor’s set is a flat, slightly raked, cracked-earth floor with a smooth egg-like stone and a lithe, tentacle-like, elegantly leaning tree, all framed by a glowing light-box frame that changes color with the time of day and a back wall of polished concrete that extends beyond the frame. The overtness of this frame imposes a tacit self-consciousness. It’s as if everything within it were quoted, enacted with awareness of all the innumerable Godots played before, even though the action feels consistently fresh, embedded in the urgent present. What is this company’s mysterious imperative to keep playing Godot? the frame seems to ask. Of course, the production must provide the only answer.

The concrete rear wall is so like Lincoln Center’s walls, not to mention those of a thousand other arts centers built on the same brutalist aesthetic, that it continues this line of thought. The true answer to the timeless question of where the play’s action takes place seems, here, to be: in an arts center, where else?!

Accessible, meticulously built, lovingly performed, Druid’s Godot has as much resonance as any cleverly deconstructed version, for those prepared to recognize it.

This article originally appeared in Jonathan Kalb on November 8, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Jonathan Kalb.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.