The Liubimovka, for those not in the know, is the annual festival of young dramaturgy held in Moscow each September, now in its 29th year. It is an important showcase of new plays by lesser established playwrights writing in the Russian language, performed in the format of rehearsed readings. The Liubimovka always falls at the start of each new theatre season, figuring as the symbolic start of the year ahead on the Russian stage. This year the festival received 646 original play scripts, of which a mere 25 made it into the main concourse and were performed over an eight-day period. This concourse took place alongside a series of workshops, as well as a one-day “fringe” program and four curated “out-of-competition” readings.

The Liubimovka offers plays by young writers from Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine who will come to define the future of dramaturgy in the region. Given the rapid and unpredictable changes that have been taking place since 2014 especially, and that continue to rage unabated, these are the voices of self-expression that perhaps speak louder than any other in the contemporary cultures of these three increasingly divided countries. The Liubimovka is a chance to see and hear these voices at their most raw and unrestrained, and in this regard it plays an essential role in the lifeblood of the Russian theatre scene, supplying it with desperately needed gulps of oxygen while it suffocates under the weight of restrictive government legislation and the ever-growing influence of the Russian Orthodox Church. In an increasingly conservative cultural climate that seeks to asphyxiate not only itself but also everything else around it into one large taxidermy museum display, the perestroika-era ideals of the Liubimovka embody a very different spirit from the one prevalent today, and as such it represents a rare opportunity to identify new trends in the emerging theatre of the present and future.

Starting with the positives, there was a strong showing by female dramatists at this year’s festival. More than half the plays in the main program were written by women, with the strongest, most original voices undoubtedly coming from this group. In the wake of the #metoo campaign in the Anglophone world, it seemed fitting that young Russophone female dramatists should also be voicing issues specific to them and their realities. Olga Shiliaeva’s operatic play 28 Days playfully invokes the model of the classical Greek tragedy to speak out on the woefully misunderstood and ill-informed issue of female menstruation. The Greek model, with the female protagonist, male antagonist, and all-female choir, allows Shiliaeva to turn a school biology subject into a funny, touching, and informative exploration of female sexuality and the body. Toward the midway point, however, the laughs quickly peter out as what starts off as light-hearted education develops into a broader reflection on the place of women in society, the inequality inherent in gender roles and social expectations, and the prevailing patriarchy that disadvantages women in professional and private life—the choir memorably singing at one point, “If men also had periods, such a law [granting time off work] would long ago have been passed, and blood-stained trousers would be normal, and sanitary products would be free.”

Shiliaeva’s instinct for rhyme and rhythm in her use of language gives the text a lyrical beauty and power that elevates the theme to yet higher levels, the effect of which on the audience was palpable. Frighteningly, this was the author’s debut play, one that should nevertheless be compulsory viewing for everyone, everywhere.

Continuing on this theme, two further plays should be mentioned—Masha Kontorovich’s The Floor Is Lava, A Whore Is Masha, and Maria Ogneva’s After The White Rabbit. Both Kontorovich and Ogneva are already Liubimovka “veterans” despite their young age, but it was still impressive to see the control and maturity with which they constructed their dialogues, character development, and narrative suspense. Kontorovich, whose Mum, My Hand Has Been Torn Off was presented at the 2017 festival, demonstrates in her new play her growing confidence and command of the dramatic form. In her previous work, the main character was a teenager, an immaturity that was reflected in the text itself, which was lacking weight. One year on, however, the main character is a 24-year-old semi-autobiographical Masha, whose extra maturity extends to all levels of the play. Kontorovich claims not to write with an agenda in mind, but nonetheless, it is clear that certain issues have filtered into her new work. The narrative revolves around Masha’s multiple overlapping relationships, reflecting the reality of life for young women in the West Siberian city of Ekaterinburg. It is difficult not to read the play as social commentary, even if it does not seek to take an active stance on the issue that I saw at its core—the social stigmatization of women in a highly patriarchal society. Regardless of this, as a work of drama, Kontorovich’s play stood out, perhaps reflecting her background as a student of the famous playwright Nikolai Koliada. Considering that this is her second play in successive years to make the cut for the Liubimovka main program, Kontorovich is one of the most promising young writers coming out of the festival scene.

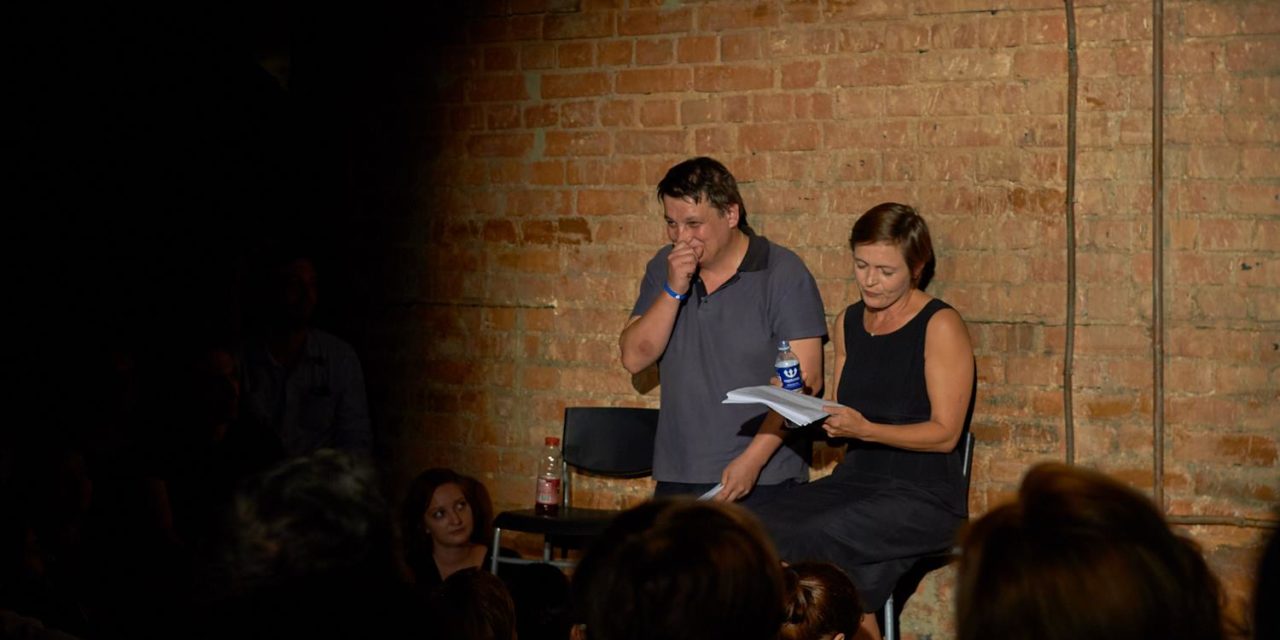

In contrast to Kontorovich’s realism, Ogneva uses the fantastical device of a Lewis Carroll-esque white rabbit to recount a horrific real-life story of the murder of two young women who got into a stranger’s car some six years ago. The victims were known to the author herself, and she uses allegory as a way into what would be otherwise an unapproachable, unstageable subject matter. This is theatre as therapy, but what results is a play of real dramatic quality that does justice to the victims while broaching a major, much broader social problem. In this respect, Ogneva makes the unstageable stageable, vocalizing that which is usually passed over in fearful, agonizing silence. The standing ovation at the end and the visible emotion expressed by both actors and audience members alike affirmed the power of Ogneva’s new work. The playwright dedicated this play to the memory not only of the two victims but also to “all the other girls, who are not to blame.” In Russia, a country where rates of violence against women are high and the law does little to protect victims or punish perpetrators (and even less since domestic violence was downgraded in the criminal codex earlier this year), this play clearly resonates in a way that few of its contemporaries can.

One trend that particularly stood out this year was the return of the “play in verse” and the formalistic devices of rhyme, rhythm, and structure associated with it. There were a total of four plays-in-verse in the main concourse, which is more than usual (last year I don’t recall there being any). This seemed especially significant because all of them were among the strongest plays of the festival. Besides Shiliaeva’s aforementioned 28 Days, these included Mikhail Chevega’s Kolkhoznitsa And Worker, Iurii Smirnov’s Files Of Dead Slavs, and Aleksei Oleinikov’s The Bread Factory. These texts were not merely exercises in formalistic technique, which modern plays that utilize verse often appear to be, and they all managed to avoid the sentimentality that such works usually suffer from. Chevega’s piece humorously and playfully reflects on the Soviet past and the legacy of Stalin through Vera Mukhina’s iconic 1937 statue of the peasant woman and the proletarian man, which famously features at the start of every post-war Soviet film produced by the Mosfilm studio. Smirnov’s Files Of Dead Slavs, by contrast, is set in the present and expresses through a series of loosely connected monologues the condition of total hopelessness and godlessness that prevails within the ongoing conflict between Russia and Ukraine. Against the climate of silence and denial about events in Ukraine within Russia itself, Smirnov’s intervention was a valuable reminder of the reasons behind the marked drop-off in Ukrainian representation at this year’s festival. Oleinikov’s The Bread Factory was the most formally structured of all the poetic texts that featured, although it also displayed a strong influence from rap music, contemporary culture, and teen slang. Oleinikov, himself a school teacher who is a daily witness to contemporary teen culture, constructs a text that for all its clever rhyme and subtle metaphor, makes a strong statement on the role of education in society and the way that it can be manipulated for less-than-noble political ends. To give away the ending, or at least my interpretation of it, the teenage characters turn out to be raw ingredients in a bread factory and end up being baked:

“We are heating up, we’ll soon burn… // We are hard on the outside and soft within.”

The presence of verse in all these plays seems to suggest that more formal structures appeal to emerging dramatists at the present time. It is too early to say exactly why this style has returned and whether it can be read into as a reflection of the reigning cultural climate—one festival adjudicator’s suggestion that the current epoch can be likened to the last time formalism reigned in Russia (and what followed) is a provocation that many will prickle at. However, if new poetic plays continue to carry the weight that these four undoubtedly do over the coming years, the reemergence of this trend is a phenomenon that should not be ignored.

The out-of-competition plays were this year chosen by Oleg Loevskii, who described his selection as “the repertoire of my ideal theatre,” “that which breaks the canon of the ordinary repertoire choice, but that nonetheless can be shown in a large theatre with columns.” The play most suited to a large stage would have to be Mikhail Durnenkov’s How Estonian Hippies Destroyed the Soviet Union, which was written on commission for a theatre in Estonia. It is a dream-like psychedelic journey where reality and the imaginary become entangled, only disentangling at the play’s denouement, when it becomes clear that while the eponymous Estonian hippies may be forced to physically submit to the will of authority, it is their ideals of love and freedom that ultimately collapse the Soviet project from within, at the level of the individual. The play that will end up getting the biggest stage, however, comes from another well-known name in the so-called New Drama movement, Ivan Vyrypaev. His new work, Iranian Conference, is neither a conference, nor about Iran, but uses these two words more as signifiers of intended meaning and interpretation. They are the starting point for a discussion of the crisis at the core of European and world civilization in the twenty-first century. God versus science, belief versus progress. It is a testament to Vyrypaev’s skill as a dramatist that a ninety-minute conference discussion about political philosophy can be so engaging and entertaining. The ending, however, where an Iranian female poet is produced from nowhere to give the final word after a European man invites her to do so, falls short of being convincing and could be construed as Orientalism. The argument that the East speaks a different language, and in this case responds to Western logical discourse with “irrational” emotive poetry, is hardly a new one. The play least likely to see Loevskii’s large stage performance is perhaps the strongest—Pavel Priazhko’s Neighbor. It is a one-act two-hander that recalls the simple yet overwhelming power of precise dialogue and silence found in the great twentieth-century works of Beckett and Pinter. While Priazhko’s previous work Black Box fell firmly in the territory of the absurd, Neighbor is distinctly more realist. Priazhko has said of his new work that it is about the relations between Russia and neighboring Belarus (Priazhko himself coming from the latter). While this is not at all evident in the text itself, the dramatist’s personal intervention in this regard adds a great deal more contextual meaning and implication to the text and also perhaps explains the more realist style he chooses to employ. In the context of playwright Maksim Kurochkin returning to his native Ukraine for political reasons and remodeling himself as a Ukrainian playwright, it remains to be seen if Priazhko’s statement with Neighbor is the start of a similar move.

Sadly, this year’s Liubimovka was also a notable one due to the tragically sudden and premature passing earlier this year of two of its driving forces over the past two decades, Mikhail Ugarov and Elena Gremina. The couple, more commonly associated with Moscow theatre Teatr.doc (where Liubimovka is hosted), were notorious as the tireless, fiercely independent voices of sociopolitically oriented theatre in Russia. Under Ugarov and Gremina, Teatr.doc had been hounded around Moscow and forced out of its premises twice in the space of two years on dubious grounds. In the wake of Ugarov’s and Gremina’s passing, the city authorities took advantage of the uncertainty by revoking the license on the theatre’s third venue, which was vacated a matter of days after the end of the festival. Teatr.doc is now euphemistically “on tour,” performing in multiple venues around the city while it searches for a new home, under new leadership. It is in this context that the festival debut of two further plays should be viewed—Ekaterina Kosarevskaia, Aleksei Polikhovich, and Zarema Zaudinova’s Torture, and Maksim Kurochkin, Ivan Ugarov, and Zarema Zaudinova’s Misha And Lena. Both these works are in the genre of the documentary play (the only ones at this year’s festival), with no material invented by the authors. Torture is a brutal, unforgiving exposé of the recent scandal surrounding systemic torture of prisoners and citizens held in custody by law enforcement agencies. It focuses on the Penzen case, where a group of anarchists were rounded up without cause and tortured into signing confessions of guilt for crimes they did not commit. The text is composed of verbatim quotes by victims, officers, and readings from the Constitution of the Russian Federation, which expressly states that all citizens are to be free from torture. It is a merciless sledgehammer of a play that smashes through the cultured façade of the theatre space. Documentary theatre is, in Zaudinova’s view, the only device suitable to the task of raising awareness of important social and political realities that are all too easily ignored in the escapism of drama as a genre. In this regard it succeeds, as the power of the work forces itself into your consciousness, making it all but impossible to think that all is well in a society where such acts are being committed against citizens on a daily basis behind closed doors. As Ugarov and Gremina were pioneers and advocates of documentary theatre in Russia, it seemed fitting that such a powerful documentary play on an important social issue should feature in the festival this year.

Misha And Lena, which is a tribute to the life of the indomitable pair themselves, is also a verbatim text. Comprising excerpts from Ugarov’s diary and Gremina’s Facebook posts, it allows for a glimpse into the extent of the battles that they went through to keep the theatre that they loved and believed in operating. It reveals some of the fears and doubts that lay beneath the resoluteness of their public face. It also brings out the hopes and ideals to which they strived, always believing in the rightness of their work until the very end. Misha And Lena throws down a challenge to all those emerging dramatists given a stage for perhaps the first time at this year’s festival: can they live up to the standards of professionalism and steadfast belief in their work that Ugarov and Gremina demonstrated over sixteen years at the helm of Teatr.doc? The cultural climate continues to deteriorate, and no one will give them anything for free, but that is the reality of the situation, and the hope is that the example set by Ugarov and Gremina can be a catalyst for the next generation to start something new, worthy of their legacy. Overall, this year’s Liubimovka was a more emotional and impassioned event when compared with last year, with significant social issues and stylistic developments coming to the fore, accompanied by heated debates about their respective dramatic qualities and shortcomings. After the undoubted success of this year’s edition, however, what with Teatr.doc now homeless once more, whatever happens between now and next September, the festival is entering a new era of its existence as it prepares to celebrate its thirtieth anniversary.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Alex Trustrum Thomas.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.