Vsevolod Meyerhold was a personality of great contradictions, and one of the movers and shakers in the 20th-century theatre. It’s not an exaggeration to say that he influenced the art of performance as much as Fyodor Dostoevsky influenced the world of literature.

Six o’clock in the morning had never looked so bad as on June 20, 1939, when acclaimed Russian theater director Vsevolod Meyerhold received a knock on his door. The 65-year-old artist looked at his wife, actress Zinaida Reich, in bewilderment. They didn’t expect any surprise guests at this time of day. Meyerhold opened the door and let three people in. They presented the director with a search warrant and an order for his arrest. It was a done deal.

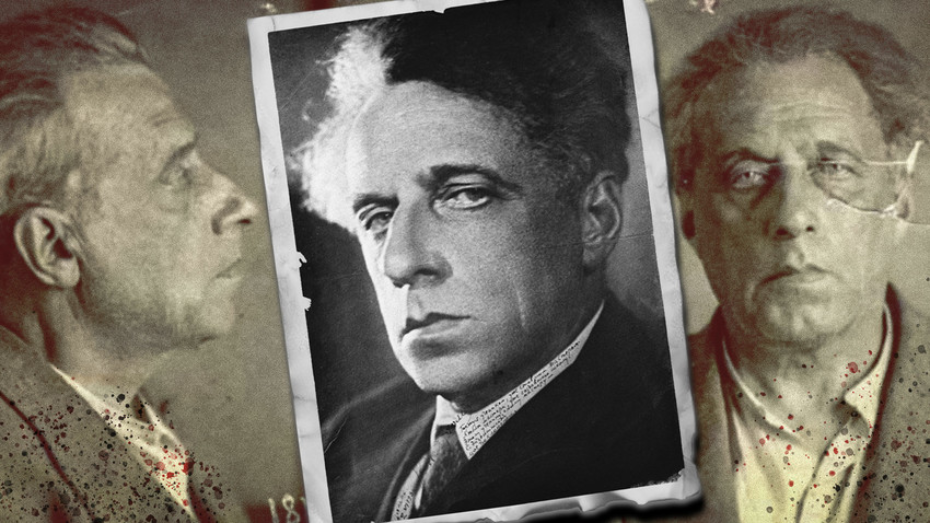

Vsevolod Meyerhold foresaw that his life would end tragically.

Photo from the Bakhrushin State Central Theatre Museum/Sputnik.

However, all of this could have been resolved in a different way, had Meyerhold listened to his friend Konstantin Stanislavsky’s most successful student, Mikhail Chekhov. The nephew of the playwright Anton Chekhov didn’t accept the Bolshevik revolution, was allergic to the communist regime, and fled to the west. In his memoirs, he recalled his meeting with Meyerhold in Berlin in 1930.

“I tried to convey my feelings to him, or rather my premonitions, about his terrible end, if he went back to the Soviet Union,” Chekhov said. “From my gymnasium years, I’ve carried a revolution in my soul and always in its extreme, radical forms. I know you are right and my end will be the one you say. But I will return to the Soviet Union. Why? – Out of sheer honesty,” Meyerhold told Chekhov.

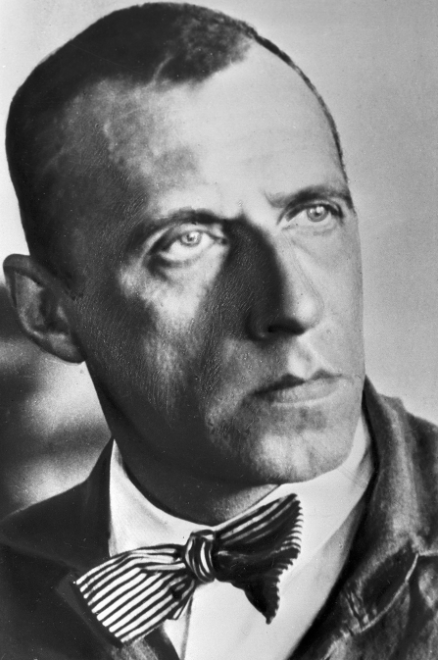

Meyerhold made his life’s work in the arts as an actor, director, teacher, and a maverick reformer. He was a complex human being, not easily reduced to a footnote of theatre chitchat. According to Sergei Eisenstein (the genius director behind Battleship Potemkin), Meyerhold was in some ways a better actor than Charlie Chaplin.

Apparently, he also had a terrible temper and his egocentric behavior made him hard to be friends with. Meyerhold admired the great Russian poet Alexander Blok and composer Alexander Scriabin, collaborated with Vladimir Mayakovsky and Dmitri Shostakovich, and had plans to work with Pablo Picasso. He spoke several languages, played violin and piano like a pro, and dreamed of building a theatrical performance like a musical score.

Early years

Meyerhold was born into a prosperous German family in the small town of Penza. His father owned a vodka distillery. Born with the name Karl Kazimir Theodor Mayergold, he had five brothers and two sisters. When Karl turned 21, he converted to the Russian Orthodox Church and changed his name to Vsevolod Emilievich Meyerhold. His first name was a tribute to his favorite writer Vsevolod Garshin, whose short and tragic life ended in pain and suicide.

Meyerhold studied law for a year before he fell in love with theater. In 1896, he enrolled at the Theater and Music School of the Moscow Philharmonic Society, where he trained under Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko. After graduation, Vsevolod joined the troupe of the newly created Moscow Art Theater.

In four seasons, he played 18 roles. He took the scene by storm and appeared in Anton Chekhov’s classic plays The Seagull and Three Sisters, as well as Shakespeare’s comedies The Merchant of Venice and Twelfth Night, just to name a few.

In 1902, Meyerhold left the Art Theater to create his own troupe that became known as the “New Drama Fellowship”. Meyerhold was a one-man band, serving as a director, actor, and entrepreneur while playing dozens of characters in around 100 performances. Between 1902-1905, he had staged around 200 plays.

Soviet life

Meyerhold welcomed the 1917 Revolution and was among the first theater artists to join the Bolshevik party. In the early 1920s, he was even allowed to set up and run his own theater, which existed until 1938. Meyerhold toured the world with his actors, performing in the UK, Germany, France, and Italy. Meyerhold also tried his hand at film production. He directed and starred in The Portrait of Dorian Gray (1915) and A Strong Man (1916).

Since 1934, one of the most acclaimed communist directors had been in disgrace with Stalin. The Soviet leader particularly disliked Meyerhold’s staging of The Lady of the Camellias, with the ex-wife of poet Sergei Esenin in the limelight. In response to criticism, Zinaida Reich, known for her biting sarcasm, wrote a letter to Stalin. The woman stated, in no uncertain terms, that Stalin was no expert in art, suggesting that if he really wanted to become one, he needed to contact Meyerhold. Stalin neither responded nor forgot the incident. The criticism continued to build. Meyerhold’s creative work was soon declared antagonistic towards the Soviet people. Although the trailblazing director probably foresaw the looming, skyrocketing problems, he still bluntly believed that his reputation, name, and loyalty to communism would save him from further trouble.

The trouble was Meyerhold refused to think inside the box. He got rid of pompous decorations, simplified theatre costume design, removed a theatre curtain, his actors had to wear little makeup. He also developed a special methodology for acting training – the so-called biomechanics, in which the ideas of constructivism were used. He believed that an actor should influence the viewer through the possibilities of his body and voice. Meyerhold ditched the principles of theatrical academism to spice his experimental performances with geometric precision, acrobatic lightness, and avant-garde poetry. His theatre didn’t conform to type and appeared to be too unorthodox to please the totalitarian regime. It was a theater boosting innovation both in style and content.

When Meyerhold’s theatre closed, none other than Konstantin Stanislavsky (who was the head of an opera theatre) gave the fellow director a generous helping hand, inviting Vsevolod to be his assistant. Although Meyerhold fulminated against Stanislavski’s System and Naturalism, he led his theater for nearly a year. Stanislavsky’s dying wish was to take care of Meyerhold. “He is my sole heir in the theatre.”

Tragic end

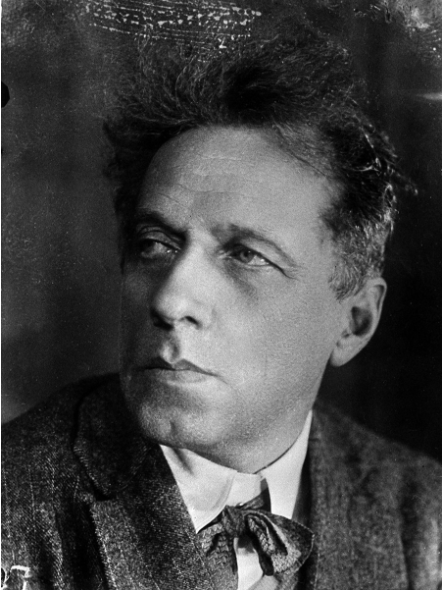

One of the most acclaimed communist directors ditched the principles of theatrical academism. Photo Credit: Sputnik.

In the height of summer 1939, Meyerhold was arrested in his apartment in Leningrad and taken straight to the Lubyanka prison in Moscow. “I was made to lie face down. They beat me on the soles of my feet and my spine with a rubber strap. They sat me on a chair and beat my feet from above,” he wrote in his letter to Vyacheslav Molotov, the Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars.

The director was exposed as a Trotskyist (One of the founders of the Soviet Union, Leon Trotsky, was Stalin’s old political enemy) who, at that time, was living in exile in Mexico (and would be murdered by a Stalinist killer armed with an ice ax in 1940.) On top of it, Meyerhold was suspected of spying for Japanese intelligence. He confessed under torture to being a spy.

But, the jaws of the totalitarian regime wouldn’t stop there, for the rules of “socialist realism” were meant not only for the theatre, but for everyday use, as well. Three weeks after his arrest, unknown assailants broke into his apartment and brutally stabbed his wife Zinaida, who died from her injuries.

Meyerhold was meanwhile sentenced to death by firing squad in 1940, his body cremated and thrown into an unmarked mass grave at Moscow’s Donskoy Cemetery. The man who refused to abandon his faith in communism was posthumously cleared of all charges in 1955.

This article appeared on RBTH.com on October 28, 2020, and is reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Valeria Paikova.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.