This proves that transnational connections can still be established in pandemic times, yet by simultaneous remote participation in place of corporeal closeness. As Wang declares in his manifesto, “[we] theatre artists, having experienced ‘the death of theatre,’ shouldn’t and can’t stand by awaiting our doom. Online theatre is no death knell for theatre, but a prelude to our future.”

Wang’s participation in Trialogue, a series of online conversations initiated by director Liu Xiaoyi (Singapore) between Liu, Wang, and River Lin (Taipei/Paris) may suggest just that: a prelude to non-mediated trans-Chinese collaborations in a future post-COVID-19 world. At the same time, Trialogue may be seen as a digital-age revival of the seminal Chinese Drama Camps that the late Singapore theatre doyen, Kuo Pao Kun (1939–2002), convened in the 1980s, sowing the seeds of the rhizomatic kind of interculturalism that defines transnational Chinese theatres.

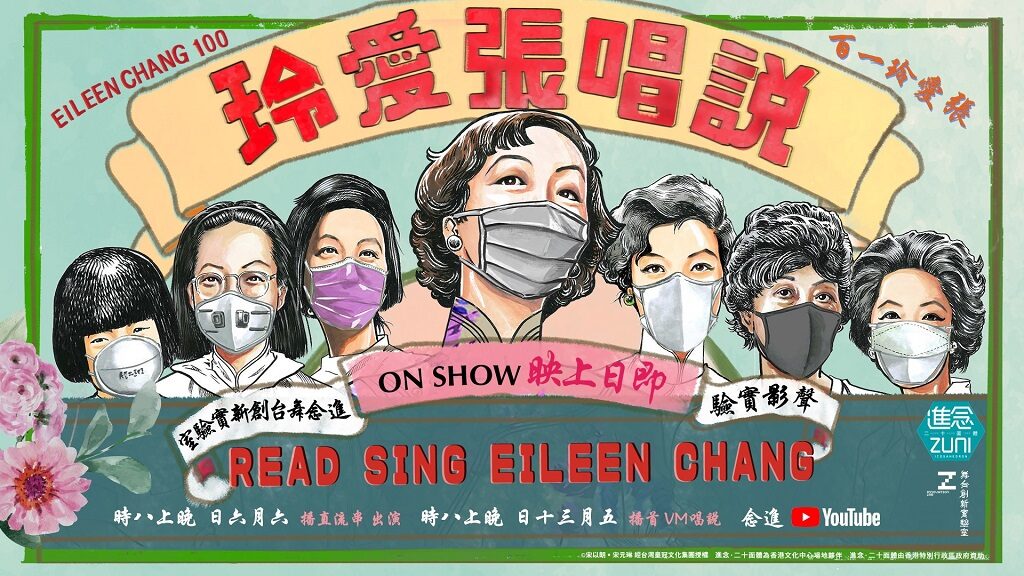

Since the forced interruption of venue-based performances in Hong Kong, Zuni Icosahedron has streamed a mixed program of archival recordings of past performances (e.g. excerpts from the Journey to the East series, originally prompted by the 1997 Hong Kong handover) and live premieres of new music- and theatre works on the company’s YouTube digital theatre channel, Z Live. The practice of creation through transregional collaboration that Zuni has pursued since the 1980s persists in the group’s pandemic-era production. Co-artistic director Mathias Woo created Read Sing Eileen Chang (live-streamed in August on YouTube) in partnership with musicians, performers, and visual artists from Taipei, Hong Kong, and Beijing to mark the 100th anniversary of the birth of the celebrated Sinophone author, Eileen Chang (aka Zhang Ailing, suitably portrayed wearing a surgical mask in the production poster). A testament to pandemic-driven challenges turned into creative solutions is also the arrangement of 300 cardboard silhouettes of “animal spirits” in the auditorium of the Hong Kong Cultural Centre during Zuni’s first live performance in months, Spirits – Piano Solo Storytelling — a collaboration with Taiwanese actor and director Sylvia Chang — to maintain the mandatory distance between seats.

Grand Theatre, Hong Kong Cultural Centre – Photo credit: Zuni Icosahedron (Facebook)

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Rossella Ferrari.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.