Taking a right turn towards Camp Kilo Charcoal Lounge (formerly Sam Tat Building) at Kampong Bugis, I spot a crew member sweeping the rainwater from the late afternoon downpour clear from the path that I will later walk on. To prevent people from slipping, I presume. These acts of care are palpable throughout the production as performers Seong Huixuan (playing Dong Xi Yan), Masturah Oli (playing Yamuna Devi Chathrapathi), Dr. Nidya Shanthini Manokara and Rachel Lum lead a group of about 15 of us through the meandering green and muddy paths of Kampong Bugis. Before the show, we are given insect repellent so we don’t get “bitten,” a cheeky yet thoughtful gesture that makes me smile. It is clear from the interview with director-writer Thong Pei Qin and programme booklet that the material Bitten explores is deeply personal, and its conscious attentiveness to the needs of its audience is part of the show’s invitation to be intimate with its histories. As I write this piece, I acknowledge the weight of confronting one’s multiplicitous personal history through performance–but as I walked with Bitten, I found it hard to keep pace, constantly feeling as though I had missed a step.

Bitten: Return To Our Roots begins with us sitting on red stools under a yellow tentage, beside a pool of stagnant water, while Xi Yan and Yamuna take on the roles of our tour guides. From the publicity video, we learn that these two characters are based on the memories and sentiments of director-writers Thong Pei Qin and Dr. Nidya Shanthini Manokara themselves. After contracting dengue fever at the same time, the shared illness launched them into a journey of searching for their shared histories, anchored by the physical space of Kampong Bugis which housed the former Kallang Gasworks, previously known as 火城 (huo cheng, Fire City). Framed as an invitation for audiences to join them on a “journey into a curious world abuzz with rich Singaporean cultures, the supernatural, and multiple truths,” Bitten thatches together oral histories and collected interviews from people who once lived, or are still living, in the area.

Yamuna starts by qualifying that she usually needs “some time to warm up” to people, while Xi Yan jokes about her name as an entry point to build rapport with the audience. I lean in, eager to know my tour guides, but their banter feels contrived and reminds me of the perfunctory scripts of tour guides from travel agencies. It doesn’t flow as I’d expect of conversations between life-long friends, as they have introduced themselves. The two performers attempt to set up a framework of reference for the show through the dengue fever-mosquito metaphor, and they pass around insect repellent a second time so we can protect ourselves. It’s a playful device, but it teeters on the edge of being gimmicky – the two performers comically clapping their hands to kill imagined mosquitoes goes on for a little too long. My attention wanes. The script makes obvious attempts to make their extensive research and anecdotes excavated from interviews more accessible, but this feels inconsistent. Some bits feel like a stiff recitation of facts, while others weave dense information and narrative together with startling intimacy, opening the audience up to the tender tug of memory and sentiment.

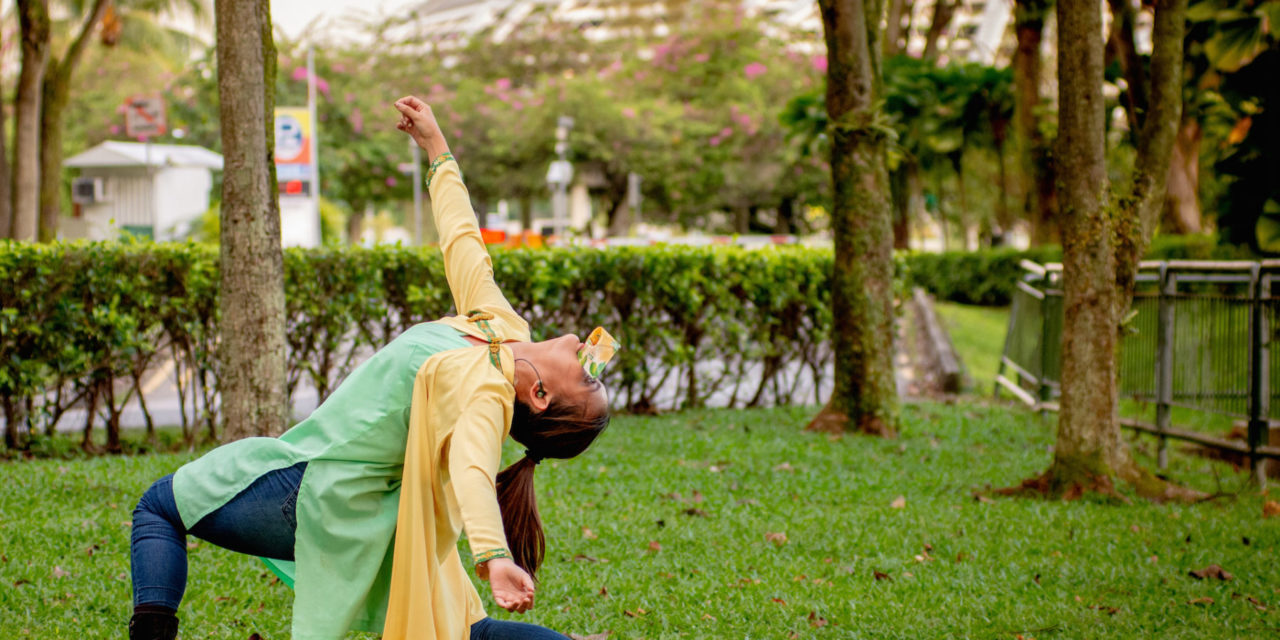

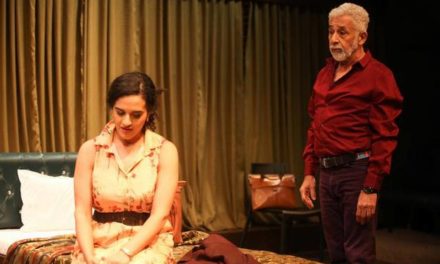

In a poignant sequence, Yamuna shares her doubts about the “authenticity” of the Bharatanatyam practice. She parses how British colonial rule first banned the dance form because it was deemed too “sensual” to be a “true” method of worship. The dance’s eventual revival sees it drastically changed as a result, from one that is fluid and full of soft lines to one that is angular and stark. While Yamuna speaks, the ankle bells ring and echo within the skeletal structure of a former gas holder as Shanthini dances around her–a shadow self. Interspersed in this monologue is a sequence where Yamuna sternly recasts Shanthini’s dance posture, enacting exactly what the colonial rulers of the past have done to the dance form. The violence of a body bent against their will bleeds through the erratic movement choreographed by Shanthini, and is incredibly effective in articulating an otherwise complex point, both intellectually and emotionally.

Yamuna (Masturah Oli); background: Dr. Nidya Shanthini Manokara. Photo: Asrari Nasir of Paradise Pictures

However, the fact that Shanthini–the person that Yamuna is supposedly based on–is voiceless leaves me uncomfortable. It feels like an act of self-silencing, a decision that remains unresolved as we are ushered to the next location. The choice of having Shanthini as part of the performing cast, but as a shadow of herself, is baffling because Pei Qin, the other person that Huixuan’s character emulates, is starkly absent. The additional layer created by having someone else act as oneself already causes a dissonance that potentially distances and distracts and the imbalance of the director-writers’ presence widens the gap even more. This isn’t ever really addressed throughout the production and becomes another emotional and logical chasm to cross.

A recurring motif in Bitten is that of blood. Mutated blood as a direct result of the dengue virus, to be specific. While blood carries the obvious and apt associations of intergenerational relations, heritage, and inheritance, the other metaphor of disease doesn’t travel. It falls flat. It drags along with it the discomfort of associating heritage and family history with disease (is it something to be “cured?”), something that, again, isn’t addressed at any point–except when the four performers are entangled in wisps of red chiffon, framed behind a rusty metal barrier. It is a literal struggle against the immutability of blood relations and the inevitability of history. But it stops there. The only reason why this metaphor has stuck seems to be because of the feverish throes of dengue that bound the director-writers together when the piece was being conceptualized, which turns the notion of blood into an inaccessible inside joke that is never fully developed. I couldn’t fully empathize with the awkward metaphor, as much as I tried.

Through Bitten, I learned facts about the histories of the area and had several glimpses into the lives of those depicted. But despite the show’s invitation, I wasn’t brought into the world so dearly held by the characters, and instead felt kept at its periphery. As we walk along the red brick wall along Kampong Bugis road, a sequence that details the history of samsui women springs to life across the street. I am presented with a lovely detail that catches me by surprise–a car’s headlights transform into spotlights. But the sequence suffers from a distance. Despite the performers walking alongside me as we make our way to the next destination, and the unexpected source of light, I remain in the shadows, outside. My earpiece rustles; Xi Yan and Yamuna’s words blur. The whimsical delight that the unconventional spotlights brought is cut short by confusion as the performers clamor to feed us disjointed information about how samsui women arrived here in the 1930s.

The audio-recordings of interview snippets that are played during the short walk to the Sri Manmatha Karuneshvarar temple also feel out of place. They seem to be clumsily stitched into the experience of the show, and the opportunity to have past residents “accompany” us as we journey is lost. There is a seemingly insurmountable tension between the lived experiences of the space and the facts that are incorporated into the production. Was it just because of the physical distance, or did the technicalities of this production bar me from their world? What went wrong? I don’t have a definitive answer.

Just as my head spins from trying to link the disparate pieces, be present with the performance while justifying parts of the production to myself, we arrive at the temple where a crew member gently cleanses my feet before we enter. Another act of care (towards the temple, its deities, and me) that I deeply appreciate. The performers share the story of how Kamadeva, the God of Love, was reduced to ashes after waking Lord Shiva up with a flower arrow. As they dance, a child who is visiting the temple joins in with peals of laughter. Yamuna, Xi Yan, Rachel, and Shanthini embrace their unexpected collaborator and dance alongside him. At that moment, the space opens up and I catch a glimpse of how people can reach each other across generations, across different contexts and histories. The playfulness present in that moment is what stays with me now, as I write about Bitten.

About the review

This review is part of the Performance Criticism Mentorship Programme with Corrie Tan, which is initiated by National Arts Council and organized by ArtsEquator. It is a six-month program during which theatre critic and mentor Corrie Tan guides mentees Casidhe Ng and Teo Xiao Ting in reviewing one performance a month from September 2018 to March 2018. The program seeks to push the writers’ and the readers’ expectations of the forms and perspectives of critical writing, as a way to expand beyond the conventional shape and depth of criticism in Singapore.

This article originally appeared in ArtsEquator on December 19, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Teo Xiao Ting.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.