When the dying King Berenger the First petulantly exclaims “Let everything die, if my death won’t resound through worlds without end! Let everything die!” his words ring as the fading despot, merged with the stubborn mewl of a child, and the rasp of the aged. In the Actor’s Shakespeare Project production, director Dmitry Troyanovsky constructs a world that also lives and dies in multiple contradictory planes: the infantile and the decrepit; the dance and the dirge; the powerful and the impotent. Much of that world rests on the pages of Ionesco’s classic absurdist work but Troyanovsky has found new colors in the work and gilded it with gold, being careful not to directly point to the current U.S. gilder-in-chief, while also being careful not to point away as well.

In Exit The King and many of his other works, Eugene Ionesco seemed uninterested in engaging with the political. At times, he would decry the construction of art aimed at political establishments, expressing his belief that, “Art goes beyond politics.” It is a sentiment as true as is it is false, especially in the theater. The reconstruction of life upon a stage, absurdist or otherwise, naturally lends itself towards the personal, the political, the theological, the philosophical. And any play with a “King,” a “Caesar,” or a “Hamilton” will naturally find itself measured against any current political environment. Therefore, it should be no surprise that this production of Exit The King finds itself kicking off Actor’s Shakespeare Project’s undeniably political 2017-18 season, entitled, “Downfall of Despots.”

Unlike Julius Caesar and Richard III, the other despots that populate ASP’s season, King Berenger is not brought low by his hubris or megalomaniacal horrors. He is brought down by the most natural of states: mortality. Berenger is unprepared for the natural, too lost in the divine right of his kingship to notice his death a mere ninety minutes away from the start of the play. His party has ended and he is unable to hear that the music had stopped a long time before. The concept of a waning bacchanalia is beautifully realized by designer Cameron Anderson’s glass cube set, littered with faded yellow balloons, and lit by a glittering chandelier still marked by small detritus from former fetes.

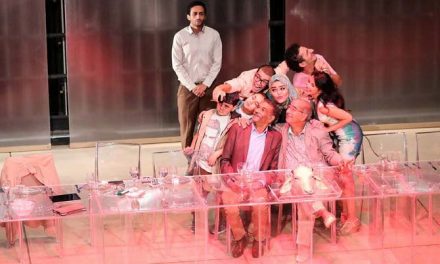

Exit The King (Courtesy Nile Scott/Actors’ Shakespeare Project)

The play opens with what reads as the end of a party and the beginning of another ritual altogether. As the small cast enters, announced by the Guard–actor Gunnar Manchester, dressed by costume designer Olivera Gajic, as a long-lost Pet Shop Boy—they are dancing to a zippy jazz tune and seemingly happy in the moment. But it is only the briefest of introductions as the two queens, Marguerite and Marie, (ASP founding member Sarah Newhouse and actor Jesse Hinson) and the Doctor and domestic help Juliette (a very nimble Dayenne Walters and Rachel Belleman) struggle with a plan to coax the King along his journey to death. The women in the King’s life present an interesting dichotomic representation of femininity as well as a fascinating relationship to one’s end-of-life. Jesse Hinson’s Queen Marie is the life of the party; the unrelenting celebration of life and love. She is sexual and emotionally volatile, resplendent in a large cleavage-baring party dress, black gloves, and Jesse’s own large biceps. It is a drag performance that calls attention the trumped-up materiality of femininity. In stark contrast to this is Queen Marguerite. Sarah Newhouse gives us a sharp Marguerite who is cold, calculated, elegant, and brutally honest. Styled as a cross between Jackie Kennedy and Hillary Clinton, Marguerite represents the acceptance of death and its discomforting actuality. She serves to shake Marie, King Berenger, and the whole kingdom out of the party and into the bright sunshine of day. In many ways, Marguerite is the crack that is said to be expanding in Berenger’s castle wall; bracing and cold but also allowing nature to come into the fortified world.

Fortifications aside, Ionesco would seemingly wish that we disregard the castle walls or oval offices where kings may reside. Yes, Berenger is a king but previous to this play the character of Berenger was also the name of the everyman in Ionesco’s The Killer (1958) and Rhinoceros (1959). In Exit The King, Berenger just happens to have godlike abilities and wear the crown. Relatability does not come naturally to this absurdist world, but Troyanovsky inches us closer to it. The king’s large red cloak is both royal red and as flimsy as a bathrobe. His scepter is an IV drip; his crown paper. Richard Snee, the jewel in this paper crown, gives Berenger the timing and smarm of an old-school late-night comedian and, by play’s end, the hollowness of a man bereft of his senses. Unlike other more recent literalistic portrayals of political leaders, decked in straw-colored (and textured) hair and ill-fitting suits, Snee’s characterization of Berenger is built on a strong characteristic of many modern leaders: charm. The King jokes, he is self-effacing, comfortably flirtatious, and cruel all at once, and is an uncomfortable reminder that even cruel tyrants can be relatable and pitiable. The terror with which Snee’s King grasps at mortality, begging for one last drop of its nectar is palpable. But it also reads as a reach for unending power and control over his domain.

Despite the obvious parallels to the politics of our day, the play essentially forces us to examine the stark realities of human mortality. According to Ionesco, the realities of mortality are incredibly personal and universal and should never be mistaken for political or partisan. In a reply to critic Kenneth Tynan, Ionesco strongly derided a political read of his work, seeing that intention as backward, “No society has been able to abolish human sadness, no political system can deliver us from the pain of living, from our fear of death, our thirst for the absolute. It is the human condition that directs the social condition, not vice versa.” For Ionesco, the fear of death propels the politics. Yet, despite the universality of death, very few men can enrobe their very human fear of death in a regal train. Very few men’s lives end in a slow slip off their throne. Death may be the great equalizer but ask those who visit Lenin’s chemical mummified body displayed in Moscow’s Red Square if death will ever make him their equal. Power always begs to remain and monumentalized long after the party ends. This production comfortably acknowledges the sighing humanity yet does not attempt to shy away from the political as well; for to shy away, as the author may wish, would mimic the futility of Berenger’s own disavowal of death.

Finally, there is nothing futile in this production as it finds a powerful voice, despite the small size of the production. Director Troyanovsky packs this play with multiple contradictory elements which heighten the absurdity while deepening the complexity of its themes. And strangely, it leaves the audience with a small discomforting idea: even the despots must shuffle off this mortal coil sometime. It’s a bizarre relief but one that is non-partisan, only slightly political, and yet a relief that I think Ionesco would also find great truth and comfort.

Gunner Manchester, Richard Snee, and Rachel Bellman in Exit The King. (Courtesy Nile Scott/Actors’ Shakespeare Project)

James Montaño is a dramaturg, playwright, and educator. Recent dramaturgical credits include: Trans Scripts (American Repertory Theater), Dream Play (Harvard Theatre, Dance, and Media Dept.), Pirate Princess (American Repertory Theater). He is currently the Education and Community Programs Fellow at the A.R.T. and is developing a devised theater piece with Boston Conservatory. He is a graduate of the A.R.T. / MXAT Institute for Advanced Theater Training at Harvard University in Dramaturgy and holds a B.A. from UMass Amherst. Mr. Montaño originally hails from Santa Fe, New Mexico but is currently based in Boston, Massachusetts.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by James Montaño.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.