As I previously noted in the review for Please Excuse My Dear Aunt Sally from September of this year, The Odyssey Theatre Ensemble is Los Angeles’ oldest 99-seat theatre complex, recognized nationally as the flagship theatre in Los Angeles for “innovation-oriented theatre and [as a] presenter of international work.” Walking into Theatre 2 at The Odyssey Theatre Ensemble in West Los Angeles to see Conor McPherson’s translation of August Strindberg’s The Dance Of Death, one is immediately struck by the set design: the gray stone walls where a conglomeration of family photos have been hung, the concrete floor showing beneath luxurious rugs, and the open windows with bars instead of curtains. The couple living here has made only the smallest effort to transform their home from its earlier status as a dungeon/prison and that decision seems to most viscerally reflect the couple’s own state of being within their marriage.

Darrell Larson and Lizzy Kimball. Photo by: Enci Box

Trapped in an atmosphere rife with the air of past punishment and with no concrete tasks to take up their time, Alice [Lizzy Kimball] and The Captain [Darrell Larson] play cards, say they will allow themselves one drink then pour three or more over the course of an evening, and argue with an off-stage cook about a dinner that never arrives. They wonder whether they should take on another lover and recall how the last threesome went. If this doesn’t sound like Strindberg to you, you’ve been missing out for not only is the play as sexually explicit as one could get in its time, it is also brutally funny and Ms. Kimball and Mr. Larson know exactly how to use both elements to their most effective ends as they engage in a slowly building battle for supremacy over the other. They are not popular with the military families stationed there and keep their own company. The first act pivots around the fact that they were not invited to a party at the doctor’s home nearby–a party one can hear well enough offstage to know that it must be a lovely one.

Lizzy Kimball and Jeff LeBeau. Photo by: Enci Box

The impact that party has on this couple is evident in the first beat of the play wherein lights come up on Alice and The Captain sitting in silence, separated in the space and focused away from each other while we hear nothing–just silence. That silence has a weight that is made all the clearer the moment we hear the music offstage, drifting in as from a home that is far enough away to feel distant, yet close enough for the couple to be able to look out their own windows and observe it with a forced air of disdain. They may not adore each other but there’s a respect that comes from them knowing each other well enough to understand what words to use to create the greatest amount of hurt and the weapon of mass destruction comes in the person of Alice’s cousin Kurt [Jeff Lebeau].

Separated from his wife and unable to visit his children, Kurt has been assigned to this island and when he arrives it is almost as if Alice and The Captain wake up after a period of lying dormant in their solitude. Alice had some kind of affair her cousin Kurt once and does everything she can to keep him to herself by pleading with him to dine in their house instead of going off to attend the doctor’s party. Kurt is tasked with setting up a quarantine station there on the island, which makes the doctor his superior officer but it doesn’t take long for him to forget duty in favor of his devotion to Alice. It should be said that none of these three characters strike the viewer as being particularly admirable–yet they are likable in spite of that. They are flawed people living flawed lives. Alice and The Captain have turned their children against each other and even when his health issues develop, neither child makes the effort to visit their parents.

There is no division between audience and set in this space designed by Christopher Scott Murillo. The Captain and Alice both come very close to the first row of audience members to look out windows and share what they see. We can credit Ron Sossi [Director of the play and Artistic Director of the Odyssey Theatre Ensemble] with choosing to keep us firmly immersed in the action. It might have been the dictates of the space but it serves the play well. There are three practical chandeliers hanging from the ceiling and all three dimly illuminate the area around the piano, the chaise, and the table. The door is always opening and closing and when characters speak about the wind it is hard not to look at the empty open windows and feel an emptiness that even the wind cannot touch. There is a beautiful sense of desperation as Alice draws Kurt into her web, freeing his inhibitions to an almost startling extent when he passionately talks about his desire to bite her and taste her – all of the poise he had when he arrived is stripped from him as the play continues and he is reduced to his animal state, wanting to eat the thing he desires.

As the play progresses into the second act, all three get caught up in the roles they are playing in a rushing frenzy to crush the other. Things come to a head when Alice makes one decision that seems poised to lead to the ruin of The Captain. We cannot tell where this idea has come from – whether it has been her secret dream all along or whether it was done in haste – but when she discovers the truth about The Captain’s state of being, the level to which they have all sunk becomes clear and even Kurt cannot overlook that to stay with Alice a moment longer. Horrified, Alice is moved enough by The Captain’s revelations in the final scene to spare him the knowledge of what she has done and in that decision, we sense her true feelings for her husband. It’s a challenging turn to execute but Ms. Kimball and Mr. Larson land it with a tenderness that makes us wish things had been different for this couple. It is hard to know what has driven them to these extremes of harm and ruin. One suspects these two would have been better off had their either been a way for them to seek a divorce without having to reduce themselves to vicious games in the hopes of [at least in Alice’s case] killing the other or perhaps if they had never been married in the first place.

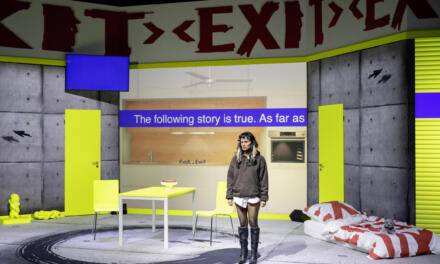

Jeff LeBeau, Lizzy Kimball, Darrell Larson. Photo by: Enci Box

Regardless, stuck with each other as they are thanks to a system that does not allow them to seek any kind of life apart, we have sympathy for these two, as doomed as they may be. Kurt might look like an innocent bystander but he played his part and more. There are no heroes here, only victims hoisted by their own petard. It is a challenge to like these people but in the end, we can understand why they might love each other after all they have done to each other. It isn’t a new idea to find the roots of the likes of Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf in Strindberg’s work here, but it is worth mentioning again if only to remind us that this is a fight for the ages that isn’t as simple as a war of the sexes. There is a deeper war to fight against anything that confines a human spirit no matter how comforting it might seem on the surface. As The Captain puts it “You forget, and you keep going.” That is how we have survived so many things, and yet that is exactly what torments us deep down. Hats off to The Odyssey for reminding us.

With Lighting Design by Chu-Hsuan Chang, Costume Design by Halei Parker, Sound Design by Christopher Moscatiello, and Prop Design by Misty Carlisle the play runs through Nov 11th.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Christine Deitner.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.