Transparency International-Russia’s recent report on the financial operations of Russia’s state theatres is yet more evidence that the anti-corruption agenda is squeezing out concerns for human rights.

On October 23, Transparency International–Russia published an investigation into the work of state theaters in Moscow and St Petersburg. This is an unprecedented catastrophe for Russia’s civil society, the full scale of which is yet to be determined.

The authors of the report insist that “the financing system for Moscow’s theatres is full of conflicts of interest. At least 14 artistic directors […] receive state contracts via their theatres, artificially creating additional opportunities for themselves to make money.”

One of the figures discussed in the report is Kirill Serebrennikov, the director of Moscow’s Gogol Center. Indeed, it was published in the midst of a campaign launched against the famous director (known as the “Seventh Studio case”), which alleges embezzlement of state funds by Serebrennikov and others. Those who have fallen victim to it include theatre managers who have worked with Serebrennikov in the past, as well as most recently Sofia Apfelbaum, a former Ministry of Culture official who is the current head of the Russian Academic Youth Theatre—she was arrested on October 26. Serebrennikov and accountant Nina Maslyaeva are currently under house arrest, while the former director of Gogol Center Alexei Malobrodsky is being held in pre-trial detention.

Transparency International experts contacted Russian prosecutors with the violations they “uncovered” and received the following answer: “Prosecutors have confirmed that [theatre director] Yury Kuklachyov and Kirill Serebrennikov broke the law when they did not notify management about deals in which they had a conflict of interest.” In the case of Kuklachyov, who runs a famous cat theatre in Moscow, the violation had to do with the fact that he rented a storage facility from his own son. Serebrennikov’s crime? Putting on plays. Or, as the authors of the report put it, “he hired the individual contractor K.S. Serebrennikov to stage productions.”

Throughout the 2000s, different people involved in Russian theatre, ranging from loyalists to critics of the government, traditionalists to innovators, have talked about how the current system of financing and accounting seriously complicates running theatres. From 2005 to 2013, the main target for criticism was Russia’ Federal Law on Public Procurement. This is what Alexander Kalyagin, artistic director of the Et Cetera theatre, had to say back in 2009 during a Federation Council meeting:

We spend so much time fighting the law [on public procurement]! The idiocy of the law when applied to the theatre is understood by all, but we can’t change anything. Theatre administrators must resort to lies that are even more elaborate than the lies they are always suspected of… All of the reforms of the last few years, starting with the treasury department, the law on autonomous institutions, the [public procurement] law have destroyed the equilibrium in the theatre. There always used to be a balance between the creative and organisational work. All of the administrative and organisational structures used to exist in order to ensure the creative process [carried on].

In 2013, a new law on a contract system in procurement was passed, but the situation did not improve. A thorough analysis of the current problems can be read in the Handbook Of A Cultural Institution’s Director Portal. The gist of its argument is that the new law makes the procedure of procuring, hiring, and paying actors and directors more difficult, and does not take into account the specific demands of what it means to work in the theatre.

While Transparency International’s report had nothing new to say about the situation in the theatre it did uncover a surprising problem: it turns out that the experts at one of the leading independent anti-corruption organizations in Russia are unable to spot the difference between corruption and violations that are artificially generated. What’s worse is that the authors don’t see the political reasons for the current state of affairs.

The Russian Constitution forbids censorship, and this prevents officials from creating a separate censorship department. This is why the authorities instead choose to limit freedom of research, speech and artistic expression indirectly. Hence the adoption of new laws and amendments in recent years, including a law against exposing children to harmful information (which includes “homosexual propaganda,” “propaganda of suicide,” and “propaganda of narcotics,”) a law against offending the feelings of religious believers, a law against falsifying history, a law against slander, and many others. And there are also ways to put pressure on the media and the arts “the traditional way”—financial dependence on the administrative apparatus, financial audits and punishments for financial crimes. Various Russian officials, including Minister of Culture Vladimir Medinsky, have said that they see the state as the client, while state-funded institutions are the contractors. The implication here being that they must toe the line and play whatever the paying client demands of them.

Under Medinsky, Russia’s Culture Ministry has adopted a consistent policy of limiting artistic and academic autonomy and making all kinds of establishments, from museums to theatres, more dependent on the ministry. A telling example was Medinsky’s 2015 move to fire the administration (and create a new repertoire policy) at the Novosibirsk Opera — in order to do this, he enlisted both the “feelings of religious believers” (which were allegedly hurt by a new production of Wagner’s opera Tannhäuser) and an unscheduled financial review.

Medinsky then fired the Opera House’s director Boris Mezdrich and replaced him with Vladimir Kekhman, an entrepreneur who has the reputation of being a swindler and who, at the time, was a suspect in a fraud case. It is obvious that Medinsky’s priority was not simply spending budget funds correctly. This is the context in which the current unwieldy legislation operates, and this is the context in which it must be examined — along with the exact ways that Russian theatre professionals violate it.

Transparency’s main claim against artistic directors is that that they receive separate salaries for staging productions in theatres they’re in charge of, and also play roles in these productions. This is what the experts referred to as “artificially creating additional opportunities for earning money.” The fact that artistic directors are forced to hire themselves is deemed corruption and a conflict of interest, as opposed to artificially-created difficulties and the flaws of a bureaucratic system that does not allow people to work normally. Transparency’s experts hold up the fact that they found similar violations in 14 out of 100 Moscow theatres examined as proof that they’re in the right.

Yet the report’s authors, it seems, did not account for the fact that artistic directors work via different contracts. This situation dictates whether or not they receive honoraria for staging productions and playing roles in these productions. Likewise, the report doesn’t address the size of the honorarium or whether they’re deserved: for example, the honorarium can be agreed with the employer when the main contract is signed, so it’s not as if these artistic directors then determine what to pay themselves. On the other hand, the report views strict observance of certain inconvenient formalities negatively: “Practice shows that seeking approval from the Moscow City Department of Culture for contracts that may imply a conflict of interest, as it is done now in accordance with current legislation, only imitates the resolution of a conflict of interest issue, and receiving approval can be seen as turning a blind eye to corruption.”

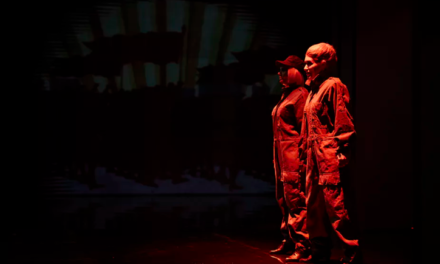

Kirill Serebrennikov near Basmanny Court in Moscow on September 4. Image: (c) Ramil Sitdikov/RIA Novosti. All rights reserved.

According to Transparency’s own definition, corruption is “the abuse of entrusted power for private gain,” yet their theatre report does not include any evidence of artistic directors making unwarranted decisions or inflating their own honorariums. But what it does include is a solution: legislative norms that combat corruption should be extended to the theatre sector, and the Ministry of Culture’s monitoring commission on state employees should be given additional powers.

These solutions are meant to make “schemes” in Russia’s theatre sector impossible. They are founded on the presumption that “everyone steals.” In practical terms, this is a proposal aimed at making the bureaucracy even more unwieldy and theatres even more dependent on the state. All of this is happening while people who work in Russian theatres are busy trying to push for legislation to preserve artistic autonomy and letting theatres work normally so that they no longer have to invent “schemes” just to get paid in the first place.

As expected, the Transparency report provoked mass criticism. Transparency’s answer to the critics made it evident that these experts have no idea as to how the theatre sector even works—and aren’t interested in finding out. Anton Pominov, the director of Transparency International–Russia, told Current Time that an artistic director is just like the head of a bus depot (“they do the same kind of job”). According to this logic, there is no difference between a director who comes up with a production where his wife plays the starring role, and a mayor who decides to “renovate” city streets in order to buy new paving slabs from his wife.

The head of Transparency’s PR, Gleb Gavrish, wrote on Facebook: “Protecting the interests of the director Serebrennikov is not our job. We are not a human rights organization.” Transparency’s press secretary Artyom Yefimov explained: “Our stance is that all laws must be followed—not just the laws you personally approve of.” There is no reason to suspect Transparency employees of unscrupulousness, of course, even though according to current Russian law they hold so dear, they are performing the duties of “foreign agents.” Transparency’s position reflects the internal problems of Russian civil society, where the anti-corruption agenda now occupies first place, having pushed out the human rights agenda.

Today, the fight against corruption and the fight for human rights are perceived to almost be diametrically opposed in Russia. This is especially evidenced in the work (and popularity) of anti-corruption crusader Alexei Navalny, and, apparently, is now a norm for civil society institutions, including international NGOs.

Yet “protecting the interests of the director Kirill Serebrennikov” is protecting the interests of society as a whole, it is protecting the fundamental rights to free speech, free expression and freedom of conscience (both officials and religious leaders close to officialdom have issues with Serebrennikov on all three of those points).

Here, Transparency’s experts are unable to grasp how an illegitimate authority is passing legislation that is unlawful in Russia. They can’t see the difference between scrupulous activity (working in the theatre, even while breaking laws that are themselves unlawful) and unscrupulous activity (sitting in the Russian State Duma and passing unlawful legislation), they refuse to include political factors in their reporting—and that’s beside the political elements in the sector they’re investigating and ethical conundrums. This willful blindness to the repressive nature of the Russian state makes Transparency International-Russia the state’s accomplice and devalues their investigation.

Transparency International-Russia’s mission statement states that democracy and solidarity are among its core values. It’s sad that they don’t understand that protecting democracy means protecting rights and freedoms, as opposed to upholding laws that repress those rights and freedoms. And that solidarity is for victims of repressions, not the prosecutors carrying them out.

This article was originally published in Open Democracy on November 2, 2017, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Nikolai Klimeniouk.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.