Despite being a revolutionary and futuristic masterpiece by Mayakovsky, Meyerhold, and Malevich, Mystery Bouffe was the first victim of Soviet censorship.

On a warm day one hundred years ago a small group of friends heard the first-ever play by a Soviet dramatist. Poet Vladimir Mayakovsky was reading Mystery Bouffe to a group that included the Commissar of Enlightenment, Anatoly Lunacharsky, and the famous theater director, Vsevolod Meyerhold.

The play was an aggressive piece of Bolshevik propaganda, opening at the Petrograd Conservatoire in 1918 for three performances, with stage decorations and costumes designed by Kazimir Malevich. This first piece of Soviet theater seemed to be pure brilliance, with three giant radical artists celebrating the Revolution’s first anniversary. But it didn’t turn out well.

Ominous start

The creative process was all but sabotaged, and the audiences indifferent. Lenin called it “hooligan communism.” But why such hostility to a show that seemed so in line with the times?

Things started ominously. A few days after the October Revolution, Lunacharsky as the Commissar of Enlightenment convened a meeting to discuss revolutionary approaches to art in the new era. Hundreds of artists were invited, but only five showed up, among which were Mayakovsky and Meyerhold.

Why such a low turn out? These were still deeply uncertain times, and even though all theaters were under Lunacharsky’s control, many artists were not sure about throwing their lot in with the Bolsheviks. But these five did. Meyerhold’s biographer, Edward Braun, called this “a hazardous act of faith.”

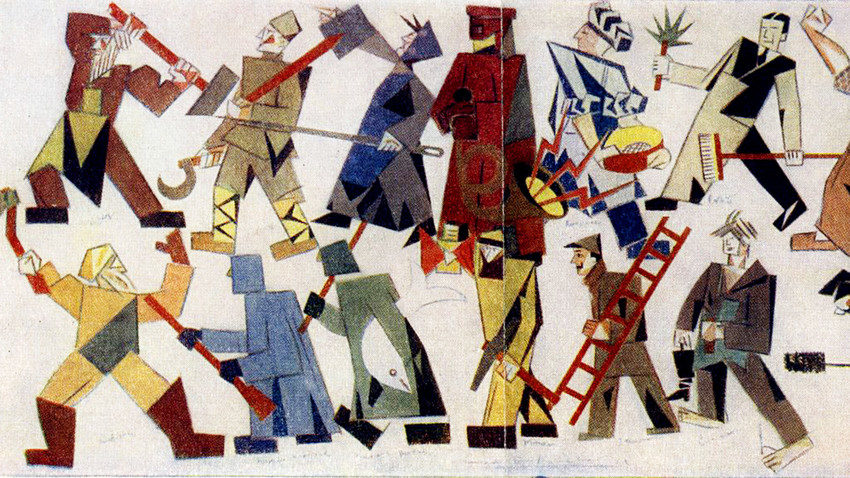

Sketch of decoration for Mystery Bouffe. Y. Levyant/Sputnik

Mystery Bouffe is by any standards a strange play, written in Mayakovsky’s trademark energetic and tumbling verse. The story is the Biblical parable of Noah’s ark transplanted into the industrial age. The flood is the Revolution, cleansing the world of the bourgeoisie. The “new common man” leads the proletariat to a mechanized paradise, where tools and even food obey humans.

The play’s cast was huge, with over 70 characters acting in a declaratory and rhetorical style. The conservative Actor’s Union labeled it “futuristic,” which according to Mayakovsky’s biographers Ann and Samuel Charters, is the “word they gave to everything they didn’t understand.”

We are certainly very far away from the living rooms of Chekhov, Mayakovsky says as much in the Prologue. Other theater gives you:

“Uncle Vanya

And Auntie Manya

Parked on a sofa as they chatterBut we don’t care

About uncles or aunts:

you can find them at home–or anywhere!”

He did not want the play to imitate observable reality. This was also Malevich’s approach to the design, as he said:

“I saw my task not as the creation of associations with the reality existing beyond the stage, but as the creation of a new reality.”

The play opened with actors coming onstage and ripping up posters of popular performances of that time. It was a declaration of war on Imperial-era theater.

Failed staging

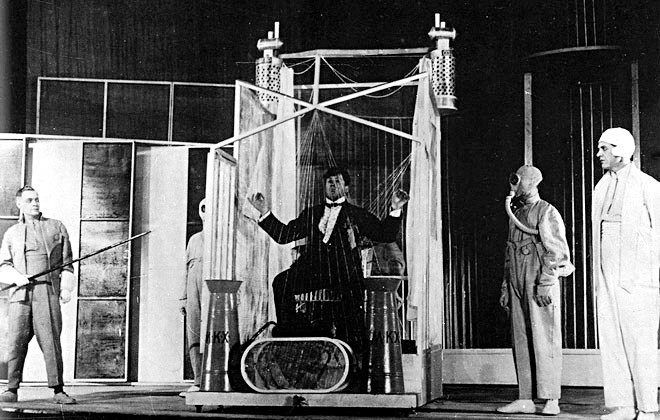

Mystery Bouffe in Meyerhold Theater. Archive photo

The Petrograd Conservatoire was less than cooperative, and they refused to sell copies of the script. The doors to rehearsal rooms were boarded shut. Nails for the set were kept under lock and key. Actors were very suspicious of the project, and most refused to be involved. An advertisement was put in the paper:

“Comrades! It is your duty to celebrate the great day of the Revolution with a revolutionary show.”

In the end, they had to use students, and Mayakovsky had to play several key roles himself.

Tellingly, most critics did not think the play worthy to be reviewed. Later, however, theater director Vladimir Solovyov wrote that,

“it didn’t get across to the audience. The witty satirical passages…[were greeted] with stony silence.”

An outdoor performance was canceled, and the Futurists were banned from participating in forthcoming May Day celebrations. Bolsheviks worried that this style would put off the proletariat.

Tragic fates

In retrospect, the experience suffered by this show anticipated the subsequent careers of Mayakovsky, Malevich, and Meyerhold. Within 12 years of Mystery Bouffe they’d all be dead, and not from old age. Mayakovsky’s suicide in 1930 was no doubt largely due to mental health issues and his complicated relationship with Lilya Brick. But his constant struggles with the authorities had a huge impact on his inability to live and create.

Malevich’s artwork was banned and confiscated for being abstract and “bourgeois,” and he was imprisoned in 1930 where he developed cancer. He dabbled in figurative art in the early 1930s, but then died in 1935.

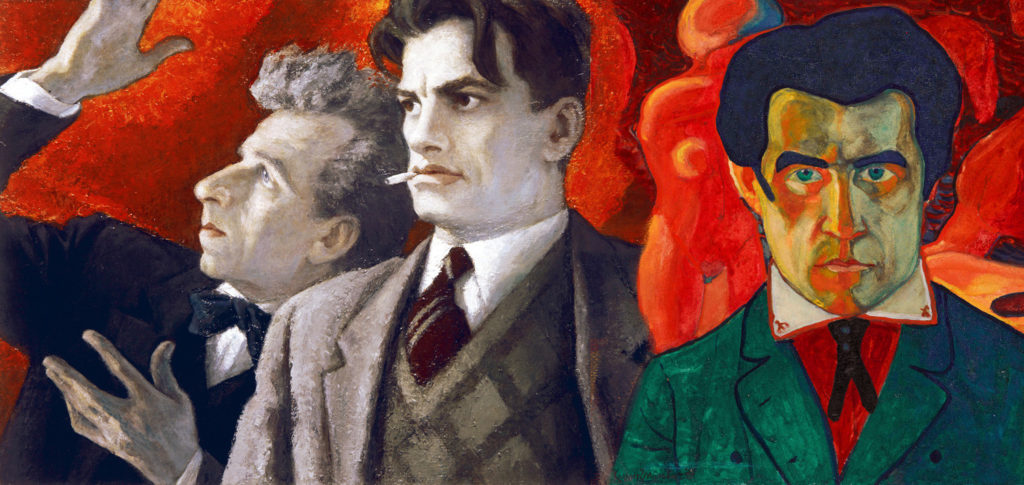

Collage, L-R: Meyerhold, Mayakovsky, Malevich. A. Sverdlov/Sputnik, Tretyakov Gallery

Meyerhold suffered the most: his performances were banned, his theater was closed, he was tortured, murdered and rewritten out of history. What began with the locked rehearsal rooms of 1918, ended in the inner chamber of Lubyanka prison in 1940.

Optimism gives way to repression

Indeed, the optimism of the Revolution gave way to paranoia, censorship, and murder in the 1930s. This is mostly attributed to Stalin’s personality and his insistence on promoting the stifling official ideology of Soviet Realism. This certainly played a huge role, but perhaps the truth is more subversive. The immediate reaction to Mystery Bouffe in 1918 was not unlike later arguments against the Avant-garde art in the purges; that it would not be immediately accessible to the common man and was therefore on the side of the bourgeoisie.

As Lunacharsky said of Mystery Bouffe, it was “incomprehensible to the new world.” The history of the play shows that Bolshevism and art had a troubled relationship from the very beginning. Even when they seemed to be toeing the ideological line, these artists were too independent and radical even in the supposedly experimental and revolutionary atmosphere of a hundred years ago.

Read more: Curtains up, shoot! How theater survived the 1917 Revolution amid gunfire

This article originally appeared in Russia Beyond on May 14, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Oliver Bennett.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.